Editorial: Station Agent

A Canadian architecture firm's people-focused proposal to revamp Britain's rail stations.

In architecture competitions, the runner-up scheme is sometimes the most interesting one. That’s the case in the recent Re-imagining Railways design competition, run by RIBA and Network Rail, which aimed to rethink Britain’s over 2,100 small and medium-sized railway stations. The winning proposal, by Edinburgh-based 7N Architects, is an elegant design with a beacon-like clock tower and a modular station layout. But a more impactful and unexpected re-thinking of the nature of infrastructure can be seen in the proposal by Toronto’s Workshop Architecture, one of five finalists selected from over 200 entrants.

Workshop co-founder Helena Grdadolnik was familiar with rural British rail stations from a stint working in the UK. “They were often an unpleasant 30-minute walk outside of town, and not that visible from the road. If you didn’t know where you were going, you wouldn’t necessarily see them,” she says. The fact that many of the buildings are shuttered, more than half of the stations are unstaffed, and few have washrooms, all make the experience even more uncomfortable—especially, say, for a woman travelling alone at night. According to Network Rail’s surveys, 61 percent of passengers do not feel safe at its 1,192 unstaffed stations.

Workshop determined that the core issues with Network Rail’s stations wouldn’t be solved with nice new buildings, but would need to start instead with having a person on-site at each and every station. In their vision, a station agent—not an employee of the railway, but a local selected through an open call process—holds the keys to the site and fosters its use by other local groups.

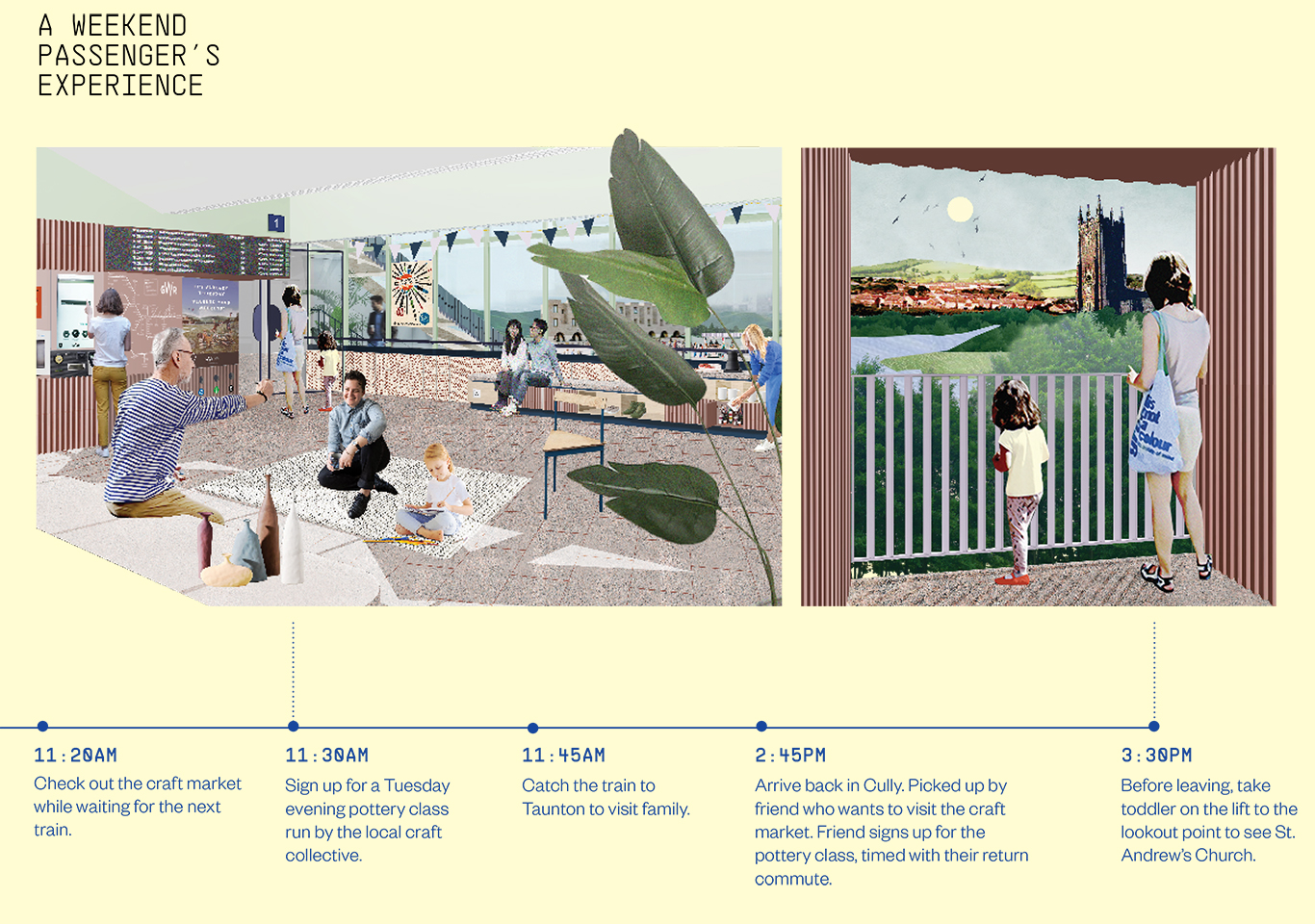

“The agent could be an individual, a collective, a not-for-profit or a social enterprise. They could be a gardener-in-residence, an outreach worker or a yoga instructor. They could manage a community kitchen, run a farm store or a book exchange,” writes Workshop. “The role can help to remove the operational barriers that keep Network Rail from allowing small stations to have green landscaping, public amenities and a fence with wide openings and multiple entry points.”

While paying for an extra person may make the project seem like a non-starter, research shows that every $1 spent through such a partnership scheme would generate over $4.60 in community benefits, increased rail ticket sales, and reduced crime and vandalism. Moreover, local stewardship could allow the rail stations to become community living rooms, says Workshop, “with cats, plants, rugs and mugs.”

While paying for an extra person may make the project seem like a non-starter, research shows that every $1 spent through such a partnership scheme would generate over $4.60 in community benefits, increased rail ticket sales, and reduced crime and vandalism. Moreover, local stewardship could allow the rail stations to become community living rooms, says Workshop, “with cats, plants, rugs and mugs.”

The proposal also saves money in its thrifty approach to the station buildings, which advocates for renovating existing structures. Such retrofits would aim to enhance their energy performance, and to convert single-purpose waiting rooms into maker spaces, galleries, and community halls.

For sites where new buildings must be created, the team envisaged bridge-like structures, with an elevated indoor community space that doubles as a pedestrian crossing over the rails. These projects would piggy-back onto an already-planned rollout of accessible footbridges. “Constructing a station building and footbridge together will minimize disruption, save costs, and be a more efficient use of resources,” writes Workshop.

For sites where new buildings must be created, the team envisaged bridge-like structures, with an elevated indoor community space that doubles as a pedestrian crossing over the rails. These projects would piggy-back onto an already-planned rollout of accessible footbridges. “Constructing a station building and footbridge together will minimize disruption, save costs, and be a more efficient use of resources,” writes Workshop.

Site planning was not part of the original design brief. Workshop nonetheless suggested that it would be key to readjust site plans to focus on pedestrians rather than parking and improve accessible access to the rail platforms. In their vision, the platforms are widened to add allotment gardens, pollinator planting beds, and shaded rest areas.

While the project did not win—in part, Grdadolnik thinks, because they did not develop a showpiece building the way that Network Rail expected—she still values the experience of developing the proposal. She believes it’s important to put architectural thinking to work not only in designing buildings, but in unpacking multi-faceted problems linked to the built environment. “For me, it’s a dream project to look at a system,” she says, “and to try to make a meaningful improvement that isn’t about our ego or a visual, but about improving people’s lives.”