Editorial: Block 2 Winner is a Canadian Choice

The first place project, by David Chipperfield and Zeidler Architecture, embraces the complex and sometimes contradictory challenges presented in the competition brief.

Architecture, fundamentally, deals in complexity. What makes Canadian architecture “Canadian” is, perhaps, its particular eagerness to engage in the dialogue that allows for seemingly competing interests to be resolved in built form.

This is inherently risky. At worst, it results in places that look and feel disjointed (“designed by committee”). But at its best, Canadian architecture is able to bring together the differing needs of human and non-human stakeholders in a single, clear and unifying vision that is palpable to those who encounter and use the resulting building.

In Canadian architecture, monumental gestures are rare, and often treated with some skepticism by Canadians. In the national capital region, even a place like Raymond Moriyama and Griffith Rankin Cook’s Canadian War Museum is sunk into its site, and is rendered as a series of subtly affecting spaces difficult to capture in a single heroic image. Moshe Safdie and Parkin Architects’ National Gallery is a bolder presence, but connected to its context by its reference to the parliamentary tower, and by its vast, wild landscape by Cornelia Oberlander.

The three top proposals in the Block 2 competition all exhibit great skill: the third place proposal, by Behnisch Architekten and Watson MacEwen Teramura Architects, takes the challenge of creating a highly sustainable building, interspersed with winter garden atria that cleanse the air and add amenity for the parliamentarians and senators working in the building. The second place proposal, by Renzo Piano Building Workshop and NEUF Architects, is a strong yet nuanced gesture: a modernist glass box detailed with care to both the quality of office spaces within, and facades crafted to pick up on neighbouring heritage buildings and motifs drawn from the parliamentary area.

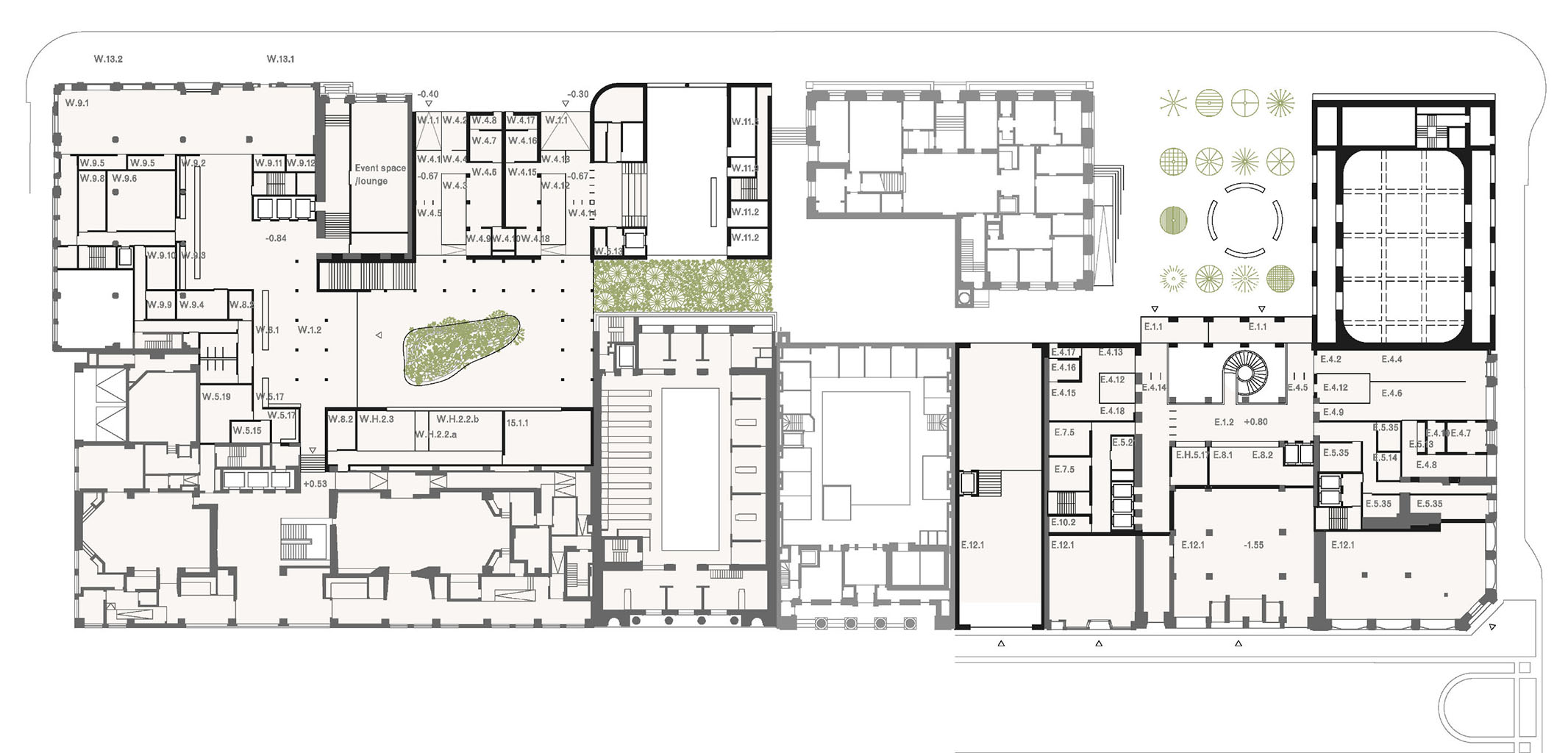

But of all the proposals, the first place winner, by David Chipperfield and Zeidler Architecture, perhaps most explicitly embraces the complex and sometimes contradictory challenges presented in the 200-plus-page competition brief. It addresses the complex heritage fabric of the site, retaining every building on the site and even stepping up to the challenge of unifying their diverse floor plates. It makes room around the indigenous Peoples Space, creating a shared plaza to the east that would allow for a ceremonial access to the building and an outdoor meeting place on axis with the Peace Tower. The configuration of the east wing keeps an open corridor for a possible link to the Indigenous Peoples’ Space – a subtle but important gesture that maintains the IPS’s autonomy, while welcoming future connection.

Unifying this is a material palette dominated by copper—a material that references the rooftops of parliament hill, as well as linking to Indigenous cultures, in which copper was highly valued. But the overall elevations, on both the Wellington and Sparks Street sides, are most strongly characterized by the varied heritage buildings retained in the scheme. These retained and restored buildings become a symbol for the notion of diversity, and a commitment to the accommodation of difference.

As with any scheme at a comparable stage of design, there are many things that will still need to evolve and change. Notable among these is the provision of universal access, which is not convincingly integrated in the current planning. As the condition of the heritage building interiors is assessed, it may become viable to suggest a selective removal of existing floors, allowing for a realignment of floor levels that would do much towards making the new complex accessible to all, as it unequivocally must be. The public realm and street level facades on the Wellington side—currently blank walls—will need to be further developed. As the client enters into direct conversations with the proponent, they, too, will no doubt bring new requirements to the table that will need to be worked the design.