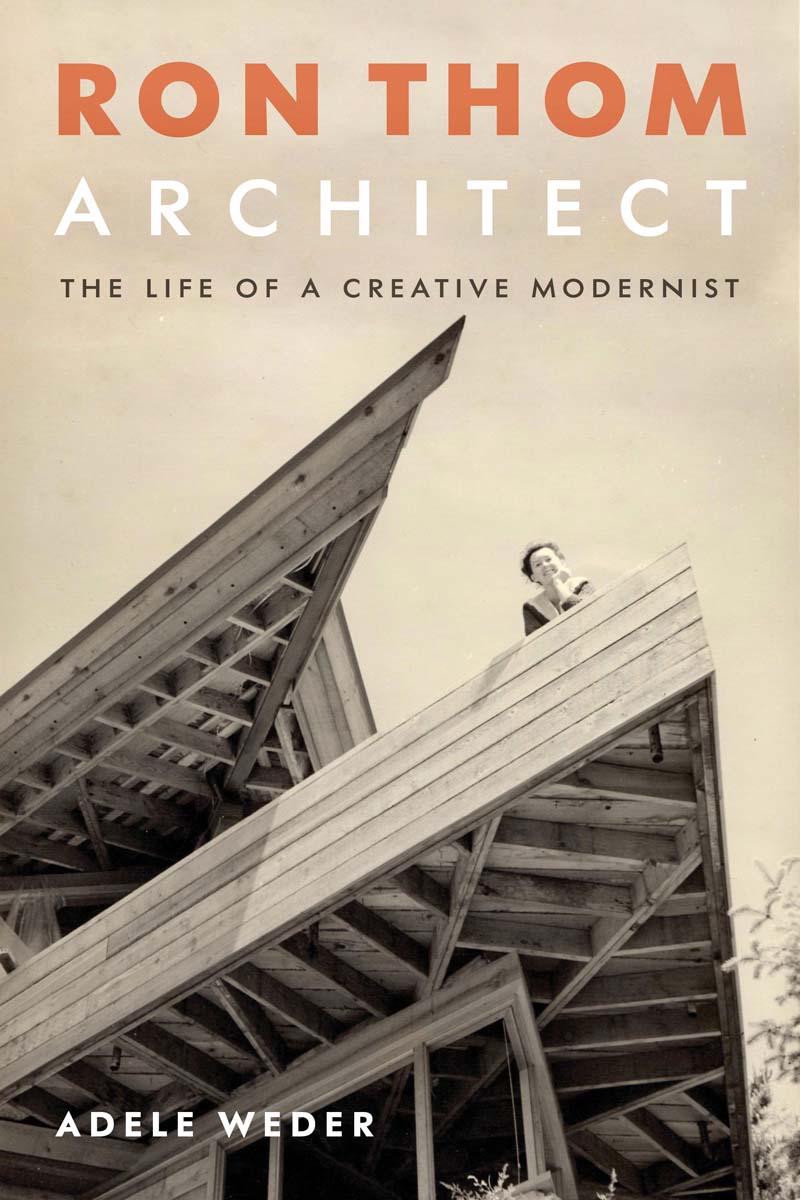

Book Review: Ron Thom, Architect—The Life of a Creative Modernist

A new book by Adele Weder chronicles the odyssey of Thom’s life and times.

“Something akin to a miracle….” This is how John Fraser, Master Emeritus of Massey College describes his former institution, designed by Ron Thom in the early 1960s. His words might equally have served as the title for Adele Weder’s recently released book, Ron Thom, Architect: The Life of a Creative Modernist. The new publication is a thorough and compassionate portrait of one of Canada’s most creative—and tormented—architects. It stands out as an intimate look at Ron Thom’s life and career, but also as a remarkable foray into the complex political, economic, and professional forces at play in any large-scale architecture project.

The book’s 21 chapters are grouped under two headings: West and East. West refers to Vancouver, where Thom grew up and started his career in architecture. East alludes to Toronto, where he settled until his passing in 1986. In the first chapters, we learn about Thom’s family and about the influence his music-loving mother had over him in his early years, as she relentlessly steered him towards a career as a concert pianist. These ambitions came to an abrupt end as the young Thom discovered the joys of drawing in high school. His true call, however came in 1941, when he enrolled at the Vancouver School of Art. There, he was taught by such luminaries as artists Jack Shadbolt and Bert (B.C.) Binning—both of whom embraced art and architecture as closely allied fields.

B.C. Binning, in particular, exercised considerable authority amongst his colleagues and students in the early 40s. After spending a year in Europe and some time in New York, Binning returned to his hometown, determined to build a house which would serve as a salon for Vancouver’s arts circle. Beyond being impactful in its time, the resulting home is also one origin point for the current book on Ron Thom. The Binning House was the topic of Adele Weder’s Master’s thesis at UBC; her research eventually led her to co-author a book on Binning, and brought greater awareness to the artist’s influence on the developing scene of West Coast Modernist architects, including Ron Thom. Weder’s growing interest in Thom later led her to curate the exhibition and accompanying catalogue Ron Thom and the Allied Arts, on display at the West Vancouver Museum in 2014 and later at Toronto’s Gardiner Museum. The present book is the final outcome of a relentless fascination and in-depth research into the life of a highly unusual architectural figure.

B.C. Binning, in particular, exercised considerable authority amongst his colleagues and students in the early 40s. After spending a year in Europe and some time in New York, Binning returned to his hometown, determined to build a house which would serve as a salon for Vancouver’s arts circle. Beyond being impactful in its time, the resulting home is also one origin point for the current book on Ron Thom. The Binning House was the topic of Adele Weder’s Master’s thesis at UBC; her research eventually led her to co-author a book on Binning, and brought greater awareness to the artist’s influence on the developing scene of West Coast Modernist architects, including Ron Thom. Weder’s growing interest in Thom later led her to curate the exhibition and accompanying catalogue Ron Thom and the Allied Arts, on display at the West Vancouver Museum in 2014 and later at Toronto’s Gardiner Museum. The present book is the final outcome of a relentless fascination and in-depth research into the life of a highly unusual architectural figure.

As Thom started his career, the power scene in Vancouver was well established. “The region’s politicians, lumber barons, mining magnates, and other corporate titans convened [at the Vancouver Club] regularly to eat, drink, smoke, gossip, and conjure up the region’s future,” writes Weder. “Architects invested in its high-priced memberships, which paid off handsomely in relationships and design commissions.”

Thom began his apprenticeship in 1949 at Sharp & Thompson, Berwick, Pratt—one of Vancouver’s most well-connected and well-established firms. Thom was taken under the wing of Ned Pratt who, according to Weder, “recognized […] that even when people wanted efficiency, they still wanted beauty.” Thom’s talent as an illustrator got him in the door, but his role soon expanded. Beyond being a workplace, TBP, as it was known, was a small society in itself, with passionate young men often staying after hours to explore new ways of building houses. Among them were Thom, Arthur Erickson, and Erickson’s future business partner Geoff Massey. Their “2 a.m. specials” resulted in striking projects, in tune with the lush Pacific vegetation and Vancouver’s amazing coastal views.

1949 was also the year the Government of Canada launched its Royal Commission on National Development in the Arts, Letters, and Sciences, headed by Vincent Massey, who was to have a major influence on the future of the arts in Canada. Serving as Governor General from 1952 to 1959, Massey also happened to be at the head of a wealthy family that would be instrumental in Ron Thom’s eventual move to Toronto.

The 50s were marked by TBP obtaining the commission to design and build the B.C. Electric Building. Weder provides helpful background on the social and political context that surrounded this new job, for which Ron Thom was designated as lead designer. The project, which involved artist B.C. Binning, was highly praised as an original, modern, and elegant take on the highrise office tower. But, reports Weder, it also fed the “rift between Ned [Pratt] and Ron, which had been widening as Ron’s fame grew.”

“In February of 1960,” writes Weder, “Ron received a letter that would change his life forever.” Vincent Massey, who had just retired from his official duties, was inviting him to participate in an architectural competition, along with Arthur Erickson, John C. Parkin and Carmen Corneil. The project was for a graduate student residence on the grounds of the University of Toronto. The memorandum accompanying the invitation stipulated that the building “should possess certain qualities: dignity, grace, beauty and warmth.” Thom, in charge of TBP’s proposal, won the competition and went on to build Massey College, “destined to be a kind of grand plot twist in the story of modern Canadian architecture,” according to Weder. Indeed, in the context of the early 60s, the carefully crafted, intimate interiors proposed by Thom were perceived by some of his contemporaries as contrary to the prevailing trend towards slick glass-and-steel modernism.

Weder describes the painstaking design process, which was totally under Thom’s control, as one that was professionally rewarding, but personally taxing. Adding to the complexity, Thom still lived in Vancouver and was juggling other commissions at TBP, all while going through unsettling divorce negotiations. Playwright, novelist, and inaugural Master of Massey College Robertson Davies described Thom in his personal diary as “a man of genius, without self-knowledge or self-protection, naked, bruised, and wandering.”

Thom’s mounting personal hurdles were to be somewhat tempered when he finally moved to Toronto in 1963. He was deeply in love with Molly Golby, whom he had met a year before while working on Massey College. He would soon be married to her. Another positive turn of events was a chance encounter on the construction site of Massey College with Tom Symons, the founding president of Trent University—a post-secondary institution in its early planning stages in Peterborough, Ontario. This meeting eventually turned into a commission to lead the design of the new university’s masterplan and first buildings—a commission, writes Weder, that “marked a quantum leap in scale and complexity from anything Ron had attempted in his career. He knew how to design stand-alone houses and buildings, but he had no idea of how to go about master-planning a university campus from scratch.”

Thom struggled with the difficult task at hand and relied on TBP’s expertise to back him up. He surrounded himself with a few talented, trusted colleagues, among them, architect Paul Merrick. Like Massey College, the design of Champlain College—the new university’s flagship building—became a kind of living laboratory for exploring new ideas. Fortunately, Thomas Symons turned out to be an indefectible champion and supporter of Thom’s creative vision. As Symons confided to Weder during an interview, “[Thom] would draw, and with just a few strokes of a pen, he would precisely conceptualize something I couldn’t even imagine. It was breathtaking.”

The resulting building, mostly designed by Ron Thom, was highly praised for its aesthetics—but the budget ran much higher than expected, alarming Trent’s cost consultants. As pressure mounted on the architectural team, Weder writes, “Ron’s architects struggled to get their projects back on schedule while producing thousands of meticulously rendered hand-drawings and details.”

Accustomed to digital tools, today’s young architects would probably be astonished at the amount of work needed to document a project or produce seductive perspective renderings. Unfortunately for Thom, even by the time Champlain College was underway, his more traditional work methods were starting to be displaced by digital drafting in the powerful corporate world, and among the most aggressive architectural firms. Weder sheds light on the anxiety the shift created among architects such as Thom, who still firmly believed in the value of intricate, time-consuming hand drawings.

Nonetheless, by the time work was completed at Trent, Thom’s reputation had grown. So had his workload and his staff. He brought in new talent, including Peter Berton and Stephen Quigley, but “floundered at the overwhelming task of running the firm,” writes Weder. Towards the end of the book, the chapter ‘Art versus the Corporate Wave’ summarizes the challenges Thom had to face as he tried to respond to this new reality. She also explores his mounting dependency on alcohol, which was to eventually destroy his second marriage and many of his relationships. Weder handles this nexus of issues that led to Thom’s untimely death in 1986 with restraint and great delicacy.

A lot more could be said about this book, which reads like a novel: tragic at times, but exhilarating in so many ways. It is particularly thrilling for those of us who believe, as did Thom, that “The architect’s role as artist must none the less continue to be the most important raison d’être for his existence—and for the existence of his profession—as it has been throughout history.”

Kudos to Weder who spent years on the research, interviews, and writing for this book. Thanks also are due to the architect’s family and his long-time colleagues and friends, who allowed Weder to access photographs and intimate documents that enrich this publication. In a country where architecture publishing can be an incredible ordeal, gratitude is also merited by Greystone Books, as they fully endorsed this publication.

The author’s hope was that anyone interested in understanding, in John Fraser’s words, “the difference between a humdrum shelter and something akin to a miracle,” would enjoy reading Ron Thom, Architect: The Life of a Creative Modernist. I believe she has achieved her goal.

Odile Hénault is a contributing editor to Canadian Architect. She studied at TUNS (now Dalhousie University’s School of Architecture), founded by Jack Shadbolt in 1961. Her first internship led her to work at TBP, where she became acquainted with a number of Ron Thom’s long-time colleagues. She later crossed paths with Ron Thom in Toronto, while she was at the helm of section a, the architectural journal she created in 1983. She published Ron Thom’s National Gallery competition entry in section a in August 1984.