2022 RAIC Gold Medal: Jerome Markson

Certain works of architecture are so carefully woven into the times, places and cultures within which they are set, they seem to have always been there. Such buildings form the settings for events both ordinary and extraordinary, shaping not only the ways we engage and remember these events, but also quietly defining how we see ourselves, through shifting circumstances wrought by time. It can be a valuable lesson to look back at the moments these buildings appeared. What was the vision that brought them into being, that imagined them as something wholly new?

Happily, the RAIC 2022 Gold Medal Jury has done just this, in awarding Jerome Markson its highest honour. Markson has spent his career creating just such works of architecture: inscribed within their contexts, imbued with a masterful level of craft and character, and conceived foremost as settings for human interaction. His practice of nearly 60 years can only be described as omnivorous, embracing a wide range of building types and programs, from single family homes, to multi-family housing, to housing for the aged, to cultural and religious buildings, to medical and office buildings—even post-office prototypes, and yes, a floating cottage. He created notable buildings of distinction in all these categories, earning over 50 design awards in the course of his career. The longevity of Markson’s practice is a testament to his extraordinary commitment, dedication, and achievements in architecture and urbanism during a period of great change, and speaks to the continuous relevance of his architecture to diverse audiences inside and outside of the profession.

Through his diverse work, Markson pursued a more open and inclusive expression of modernity, one that moved away from the doctrinaire, object-focussed Modernism widely accepted in the mid-twentieth century when he began his practice. Architecture critic Christopher Hume has observed that Markson is “the rare architect who creates cities while designing buildings.” Indeed, Markson’s buildings are as attentive to the way they reshape their sites and affect the city as they are to providing rich possibilities within newly created spaces.

Early in life, Markson experienced the resonant complexities the city could present. Born in 1929, he grew up in downtown Toronto between two vibrant immigrant neighbourhoods, Kensington Market and the Ward (now vanished). His parents, Etta and Charles, were children themselves when they came to Toronto around 1900 as immigrants, from Lithuania and Poland respectively. The Markson family’s home still sits on the north side of Dundas Street, now facing the lilting portico of the Art Gallery of Ontario. The family lived on two floors above the street-level medical practice of Dr. Charles Markson. More than once, Markson’s father was paid with a chicken from patients who had no money to spare for medical care.

Seeing the struggles of his neighbours in the Depression years made a profound impact on Markson, inculcating a deep sense of obligation to help others, and a desire for greater social inclusivity. A keen observer, Markson also saw the dignity and vitality in more ‘ordinary’ buildings that constituted the fabric of the city around him—Toronto’s neighbourhoods filled with modest housing types, its mercantile blocks, storefronts, and warehouses.

Enrolling at the University of Toronto in 1948, Markson joined a class that spent its first year at drafting boards set up in a former bomb factory in Ajax, Ontario. Eric Arthur was a forceful presence in the faculty, and his arguments for recognizing the irreplaceable cultural value of the city’s heritage buildings resonated with Markson. Markson also discovered the work of the British Townscape movement, led by Gordon Cullen, Nicholas Pevsner, and others who argued that the incorporation of new, Modern buildings should be based on spatial relationships and visual sequences calibrated in relation to the existing urban context—counter to the Modernist preference for more singular, object-oriented buildings.

Another profound influence on Markson was Eliel Saarinen, whose pedagogy he encountered during a summer program at the Cranbrook Academy of Art. Saarinen’s philosophy of “always design[ing] a thing by thinking of it in its next biggest context—a chair in a room, a room in a house, a house in an environment, an environment in city plan” struck a chord with Markson. At Cranbrook, Markson also met a talented ceramic artist from Winnipeg, Mayta Silver. They were married following Markson’s graduation in 1953, and after saving money to travel, embarked to Europe to experience firsthand the buildings Markson had studied in school.

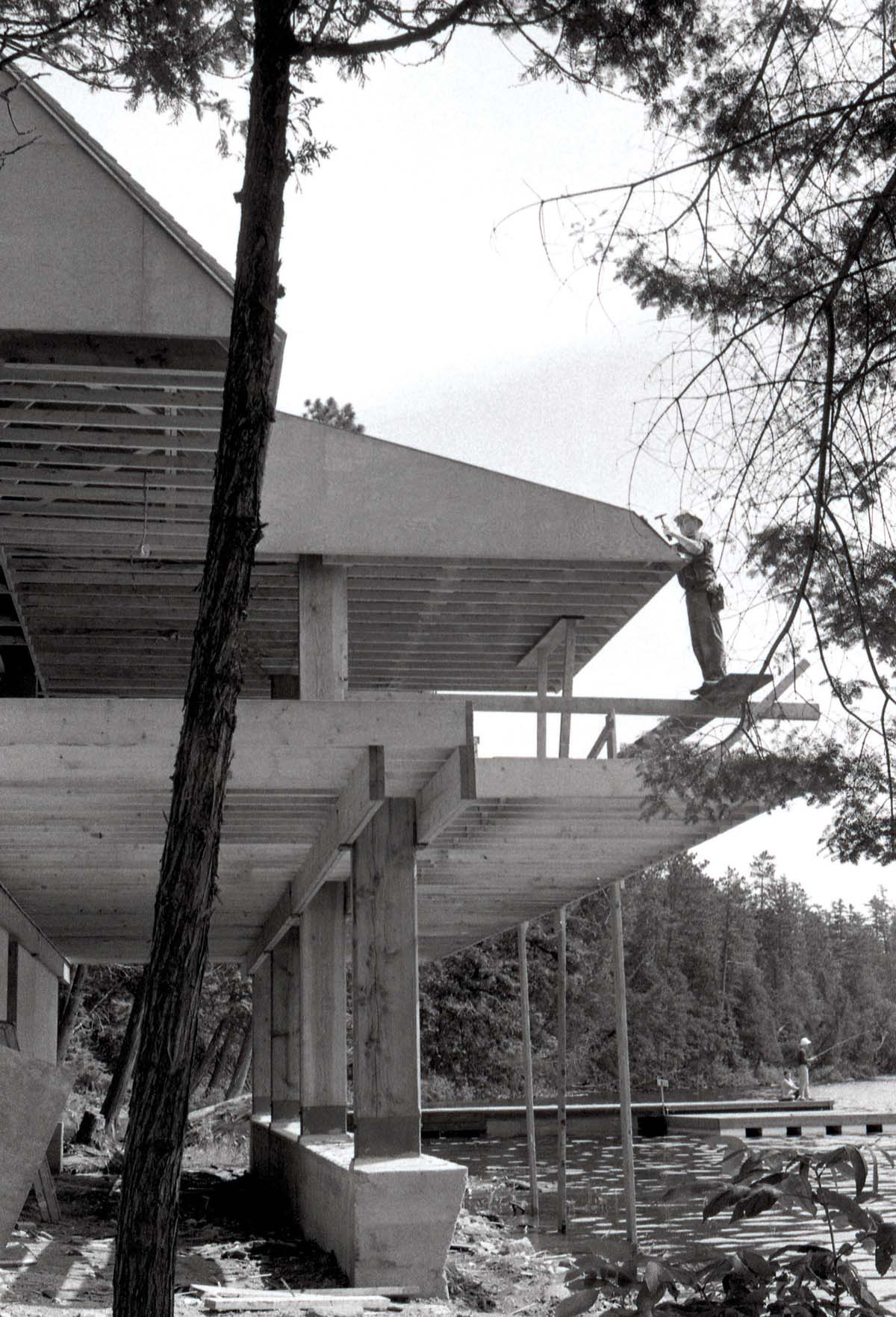

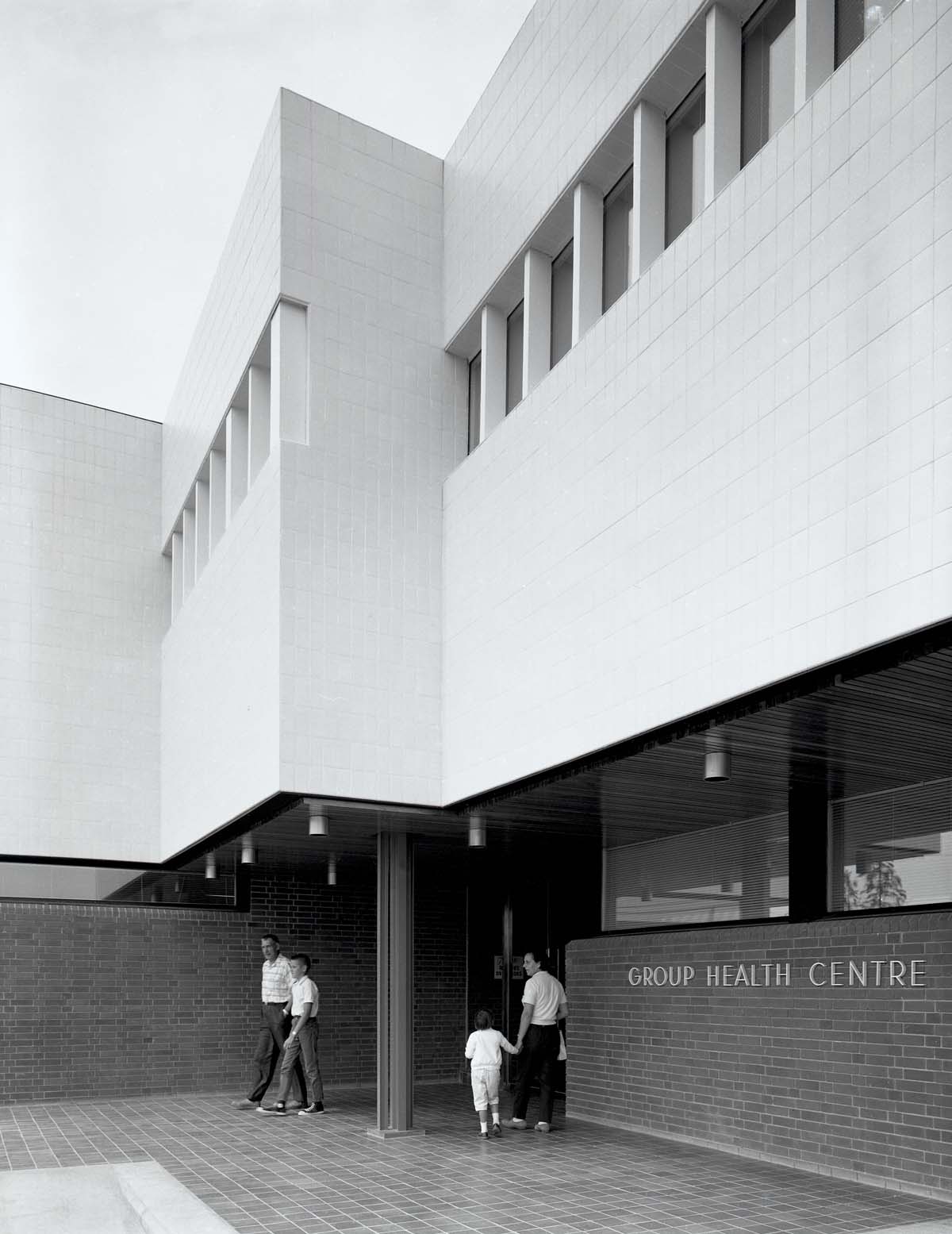

The Marksons returned to Toronto and Jerome opened his office in 1955. It was an exhilarating moment to embark on practicing architecture. Urban planner Macklin Hancock summed up the spirit at that time: “Canada suddenly flowered, it wanted to be modern.” Markson’s architectural and urban works from the 1950s and 1960s, particularly those in Toronto, were created at a time when many were discussing the ideals of a progressive society within the context of post-war prosperity. Although fewer in number, his buildings outside Toronto, too, gave architectural expression to important social developments and innovations of their time. The emergence of socialized medicine was registered in Markson’s groundbreaking design for the Sault St. Marie Group Health Centre, demonstrating that a systemic overhaul in the name of greater social equity could also spark a more humane model for spaces of treatment. His thoughtful designs for speculative model homes at Seneca Heights and the density of his Concept 3 stacked townhouses in Bramalea suggested distinct alternatives to the self-same houses of a rapidly expanding suburbia. Markson’s Elliott Lake Plaza showed that the increasingly ubiquitous strip malls proliferating throughout Canadian cities could have civic potential. And, in a period of intensive post-war urbanization and consumerism, Markson forcefully recalled the importance of wilderness in the Canadian imaginary in such buildings as the Sherman Staff Lodge, hovering at the edge of Lake Temagami; the exuberant collection of buildings at Camp Manitou-Wabing; and the improvisational rusticity of The Shack, Uxbridge.

Architectural Practice as City-building

The question of not only where social housing for the needy should be built, but how it could better value—and even learn from—the existing city was central to Markson’s design of Alexandra Park Social Housing (with Klein & Sears and Webb Zerafa Menkes). This was Markson’s first public housing work and represented a radical departure from the sterile paradigm of concrete towers-in-the park. Markson and his collaborators proposed brick, mostly low-rise walk-ups with ground-level access, laid out as a series of undulating units with wood bay windows and individual entries, interspersed with garden courts configured to preserve heritage trees. All was consistent with the scale, and using the materials of, the surrounding urban housing. It was a humanistic retort to the state of housing for the ‘needy’ that to-date had been erected through massive urban clearance. While the architects’ plans to preserve key buildings within Alexandra Park’s site area (another groundbreaking idea for that era) were rejected, Markson achieved this goal a few years later. His Pembroke Mews Co-operative integrated historic and vernacular structures with new housing—one of the first urban infill projects in Toronto.

Later, Markson designed the critically acclaimed David B. Archer Co-operative Housing as part of the massive redevelopment of an industrial area south of the St. Lawrence Market. The Co-operative took shape as a combination of townhouses and apartments, with a seven-storey apartment building across from the linear Crombie Park, transitioning in height at abutting side streets to two- and three-storey townhouses. An assortment of intermediate-scale architectural elements—window surrounds, bay windows, corner posts, and porches—brought a sense of animation and identity to the red brick street elevations, each developed according to the street typologies they fronted. Built in the still-early years of postmodern architecture, the Archer Co-operative demonstrates the syntactical richness possible in the composition of architectural elements integrated into a scalar logic, and their role in creating both urban variety and continuity.

Markson’s nearby Market Square has been recognized and awarded for both its architecture and the exemplary quality of its urban design. Its sensitive siting and shrewd use of the courtyard typology allow the building to be relatively low-rise yet high-density, and its split massing constructs a visual and pedestrian axis with St. James Cathedral one block to the north. Urban designer Roger du Toit referred to the complex as an “essay in modern design.” The modulation of Market Square’s bulky exterior—from the expression of its structural frame and recessed infill panels, to the building’s generous windows with their elegant, recessed brick jambs, to the distribution of tall glass bays—suggests the forthright efficiency found in nearby industrial loft buildings, yet, in its refinement, Markson’s design stands apart.

The museum designed by Markson for the works of Group of Seven painter Frederick Horsman Varley in Unionville, Ontario, deftly negotiates between a historic city fabric and modern development. Markson placed his Varley Art Gallery slightly off-centre at the juncture of the quaint town centre and a new, wider road, creating an open plaza at the terminus to historic Main Street, while also mirroring the openness of parking surrounding the town’s nearby hockey rink. Writes critic Christopher Hume: “Markson’s willingness to serve the city, to blend with the urban fabric, mark him as an architect of rare selflessness and sensitivity.”

A Deeper Signature: Design, Experimentation, and Expression

Markson’s choreography of architectural program and site is clearly seen in his single-family house designs, a staple of his practice. Markson’s study of the emerging suburbs resulted in a diverse array of houses, each considering how the car engaged the domestic program, and how a house could better engage its site. The Moses, Smith, and Minden Residences, Seneca Heights Model Homes, and the Chatelaine Design Home ’63, as well as later houses such as the Enkin Residence and the Ravine Residence, are but a few examples of how Markson deftly orchestrated the routine movements of daily life within his rich architectural frameworks.

Markson considered each iteration of a particular program or typology as a new opportunity to test and extend design solutions to the problem at hand. Rather than being concerned with establishing a signature identity for his work, he consistently sought new orders of program, space, sequence, material expression, and form. Markson’s design philosophy gave priority to an open, experimental process of inquiry and saw construction as a critical extension of his process. This, along with his commitment to work for a diverse mix of clients, led to a body of unique and distinct works of architecture.

Inventing a Diverse and Representative Material Idiom

Near the mid-point of Markson’s career, architect and theorist George Baird observed:

Markson has … pursued a quite individual course within the territory of Canadian architecture… [T]here is … in the best of his works a characteristic almost unique in contemporary Canadian architecture: a subconscious tactile iconography of the materiality of building, a materiality that is, for me, reminiscent of some aspects of the work of Aalto and Le Corbusier. Albeit an elusive characteristic of any contemporary architecture, this is particularly important in the Canadian context on account of its extreme rarity here.

-George Baird

Rather than based in a purely craft tradition, Markson’s architecture uses materials and building elements that communicate viscerally through experience. Diverse influences—particularly Aalto, Britain’s Townscape movement, Arthur, and Saarinen—but also, crucially, encounters with vernacular architecture both in Canada and in Europe, were instrumental in Markson’s development of a pluralistic, materially oriented approach, one that innately recognizes the intrinsic qualities of the city’s historic fabric.

Markson’s cultural and community works, despite their institutional programs, reflect his commitment to such material exploration. His Cedarvale Community Centre delineates the building’s utilitarian spaces—offices, changing areas—as a dense package of cellular rooms. That same utilitarian logic might have been extended to the collective community assembly space. Instead, Markson fashioned that space as an amorphous figure, a space at once explicitly about form, but also, at times, formless. The compound curvature of its primary exterior wall and its diffuse light sources contribute to a sense of shifting perceptual boundaries. The specificity of the wood ceiling and beams within the gathering space counter this ambiguity with a distinctly warm, immediate material presence.

His Regional Headquarters for the International Woodworkers of America is an essay in wood and brick: a lightly scaled, even delicate post-and-beam structure spans between two sidewalls of brick. Its interior spaces are lined with a textured wood tapestry emphasizing a sense of containment and interiority, strategically juxtaposed with views to a ravine, incorporating the larger landscape into the architectural ensemble. Other buildings for sites in natural settings also have a loosely expressive, improvisational quality, attributable to Markson’s choice of wood as a primary structural material. The incrementality of wood framing facilitates the minute adjustments that allow a wall to splay out, such as at his early buildings for Camp Manitou-Wabing; a roof to sweep and flare at Cedarvale Community Centre; and a large structure such as the Humber Arboretum to appear as a fragile, tree-like form hovering over the landscape.

Photo Roger Jowett

Markson’s understanding that light is not only a medium of architectural expression, but also has the potential to heal, led to his invention of a new typology for medical facilities at his Sault Ste. Marie Group Health Centre, built at a time when the prospect of socialized medical care was being hotly debated across Canada. The ubiquity of the hospital atrium today and its current association with retail spaces may obscure what a real innovation Markson’s design was at the time. Markson excised an open core of light from what ordinarily would have been densely packed, functional floor plates. Architecture critic Hans Elte saw Markson’s innovation quite clearly, and his comments are worth quoting in full:

Among the agencies of atmosphere is light … It has played a major part in stimulating this remarkable space, resulting in an atmosphere of sheer lucidity, which incidentally, no photograph or film could accurately portray. Its designer has been roused by a love affair with light.

Over many medical institutions both large and small, there still hangs, in a rather remote way, something of the cloud of gloom always present in the ancient ‘maison de Dieu,’ a place where there was little hope for life, a place where one could go to die rather than to get well.

There is no doubt that it has been the great merit of this architect that he has been able to make a most capable attempt to reverse the symptoms of this phenomenon. Whilst walking through the building, it is manifest that he had a bold flair for the unusual and, a marked perception for the poetical.

-Hans Elte, architecture critic

An Architecture of Empathy and Dignity

Markson’s multi-unit housing works were an essential part of his practice. These projects were the fullest expression of Markson’s belief that architecture is not reserved for an elite class of users, but should rather be fundamentally democratic in its ability to frame lived space and its occupants with dignity. He has said, “Why should [Alexandra Park] be different-looking than houses for the more well-off? We are all human beings, for God’s sake.” His close attention to the design of housing units in that project—varied unit types with individual access to the ground, featuring architectural elements such as V-shaped bay windows conceived as “punctuation along the street”—brought a human scale to the housing complex, enriching the texture of residents’ daily experiences moving through pedestrian pathways throughout the site.

In True Davidson Acres/Metro Home for the Aged, Markson considered how each resident might use and occupy their living space, and their needs for privacy and social connection over time. He created an innovative unit plan for the rooms, allowing discrete territories and views to be claimed by each resident. In so doing, he refashioned a space where the extent of engagement became a matter of individual choice, preserving personal dignity and privacy while offering the potential for sociability. Creating ambiguity in a space precisely shaped, yet open to divergent uses and interpretations by its occupants, reveals the generosity in Markson’s architecture.

Cultivating Architecture as an Inclusive Spatial Setting

Understanding space as an empathic medium, and architecture as a material and spatial setting for human interaction and the appearance of the individual, recasts the object-focussed propensity of Modernism into a more inclusive construction. This is reflected in Markson’s photo-documentation of a number of his architectural works. Instead of sterile formal compositions, we see adults, children, families, friends, and sometimes pets—present, and occupied with their comings and goings, their hobbies, their conversations, and their play. Markson’s images provide insight into how a key aspect of his work was conceptualized: the character of his architectural settings is inseparable from the human characters who would be an integral part of those spaces. “If not for the people who will inhabit it, then who is the architecture for?” Markson has asked.

When recorded, these images must have been arresting, even poignant. Today, some years later, the same photographs are certainly so – the familiar objects and appearances of everyday life, from objects in a household to how people dress, is more distant. Markson’s architectural settings impart the specificity of an individual’s experience at a particular point in time; because of this specificity, we can empathize with the shared aspects of that experience today.

Markson’s compassionate, humanistic approach to design ultimately transcended formal preoccupations in favour of a more immediate material and spatial dialogue with its users. A similar concern has been taken up anew within contemporary architectural practices, witnessed in the work of architects such as 2021 Pritzker Prize winners Lacaton & Vassal, who position their architecture with respect to the occupants of their buildings ‘completing’ the architecture in an active way. Decades earlier, Jerome Markson’s compassionate, humanistic approach to design transcended formal preoccupations in favour of a more immediate material and spatial dialogue with its users. The continued relevance of his architectural approach and works is evident.

Markson’s recognition of the essential role that constellations of individuals play as they appear, and are brought together, in the inclusive, collaborative construction of architectural space is at the core of what our most ambitious work as a profession can achieve. Perched as we are at the far edge, hopefully, of a global pandemic, still suffering from loss and social isolation that we have endured, many of us long for a return to the architectural settings of everyday life that Markson envisioned and built—an architecture that situates diverse human experiences in exquisitely composed and spatially rich settings, enabling participation within a shared social and temporal space.

Laura J. Miller is Associate Professor of Architecture at the Daniels Faculty of Architecture, Landscape, and Design at the University of Toronto. She is the author of Toronto’s Inclusive Modernity | The Architecture of Jerome Markson (Figure 1, 2020), and is currently working on a book about the history and urbanism of Toronto’s PATH network.