Voices of the Unheard: Making injustices inherent in architectural education and practice visible

Ten years ago, on my first day of architecture school, I walked into a lecture hall filled with Apple laptops—something I could not afford—and felt an overwhelming sense of inadequacy. I asked myself: do I belong here?

This was perhaps my first encounter with how privileged the underpinnings of both the education and profession of architecture really are. I had stepped into a profession that took pride in its students flying to Europe to intern for renowned architects for no pay—and then celebrated this fact upon seeing it on their resumes. This idea of “success” contributed to a culture of competitiveness in the school, which, along with a primarily Western, Eurocentric bias to theory and practice, would have a lasting impact on my architectural education.

On completing my undergraduate degree in architecture at the University of Waterloo, I had not yet reconciled the education I had received with my path forward to become an architect. I realized that I lacked a meaningful relationship to architecture. Yearning for this connection, I began my master’s degree feeling a pull to reconnect with my heritage. With my notebook and camera in hand, I flew 12,000 miles to my native Sri Lanka to pursue my thesis, studying the meaning of Home, Place and Belonging.

Arriving in Colombo, I had not accounted for the monsoon rains which halted my travels, and this led me to discover that my grandparents’ old home had been converted to a Montessori school for children whose families were seeking asylum. The small building was falling apart: paint and concrete chipping, roof joists broken, and the lacquered floor worn out by decades of bare feet. There was a clear task in front of me. I decided to spend the remainder of my time in Sri Lanka renovating and repairing the Montessori school.

Every time I approached this work through the lens of my architectural training, I reached a dead end. I began to realize that the process of revitalizing this school was a form of education in itself. By embracing the challenges and complexities of the project, along with the multiple voices of its stakeholders, I was able to see the question at hand: How would I create a sense of belonging for the children that attended the school?

On completing my master’s thesis, these experiences remained dear to me.

Several years later, after moving to Washington, D.C., my reflections on Home, Place and Belonging became sharply heightened by the political unrest of my immediate context.

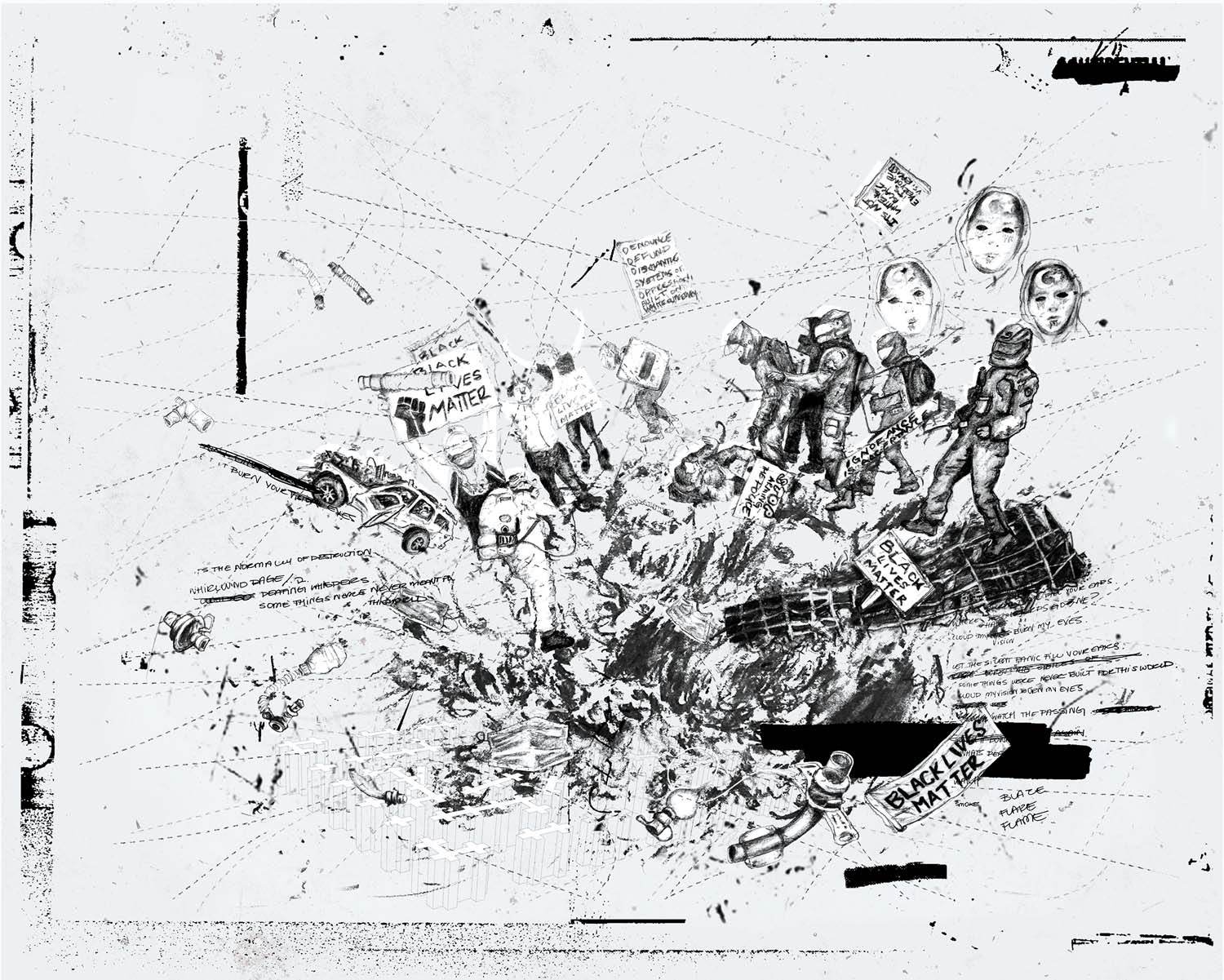

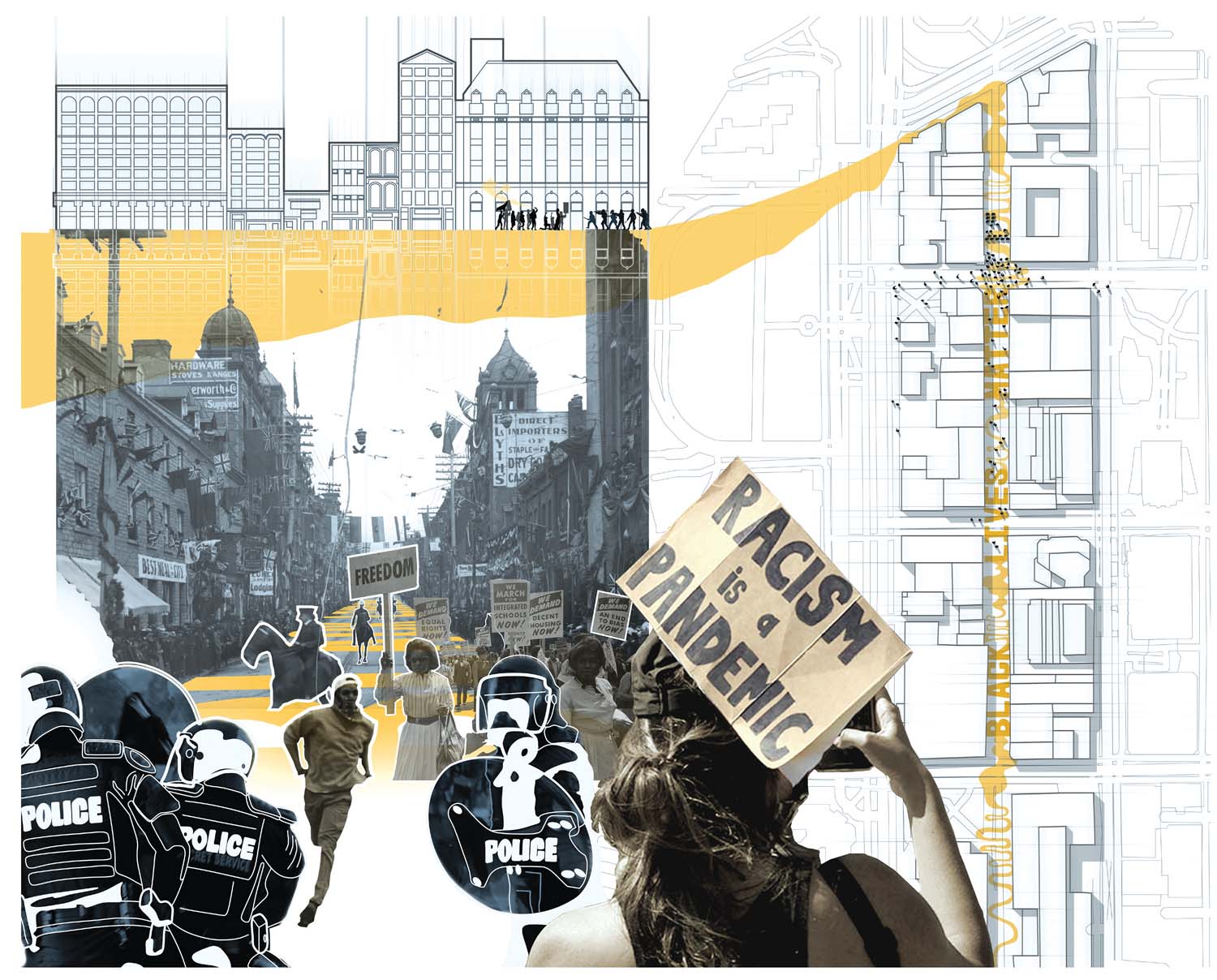

On June 1st, 2020, I found myself at the front lines of the Black Lives Matter protest at Lafayette Square outside the White House. My arms were raised, fists clenched tight, and with all the other enraged voices, I chanted at the top of my lungs the names of those murdered in the recent weeks. The people around me erupted with anger, outrage and heartbreak, compounded by the struggle, loss and danger of the ongoing pandemic.

The month leading up to this day had been a complete blur filled with powerful protest, tear gas, and continued discriminatory acts that echoed centuries of systemic racism—but this day was different. On the evening of the peaceful protest, National Guard officers rushed in unexpectedly, throwing tear gas canisters at us, knocking down those around me, and in a storm of flinging shields and batons, unloading a barrage of rubber bullets on us. This was an attack against democracy; an assault against freedom. I walked home that day grateful to be alive, thinking how privileged so many of us are to be able to walk down the street without fear of being attacked for the colour of our skin, our identity, or our beliefs.

As the world shook with the devastation of these events, people looked towards their communities for answers. Slowly, a more resilient hope began to inspire a new sense of community. Heartbroken by the brutal murders and the violence against protesters, I too longed for a meaningful sense of community. I spent my mornings and afternoons volunteering with the World Central Kitchen initiative in Washington, D.C., where I worked with a team dedicated to preparing and distributing thousands of meals to those disadvantaged by the pandemic. After leaving the kitchen each day, I joined a large group of protesters in the city and marched for hours, propelled by the powerful voices around me. During the same period of time, my close connection to the University of Waterloo architecture community led me to organize several initiatives and virtual spaces for much-needed conversations with students, faculty and alumni around these issues.

A sense of empathy was foundational to all these initiatives. It quickly became clear to me that when we gathered together in these physical or virtual places, what we were confronting and wrestling with was the question: What does it mean to be a human being?

In the weeks that followed, architects and architectural organizations struggled to respond to the events that had occurred. Many institutions issued letters that failed to meaningfully capture the magnitude of the issues at hand—perhaps because it is difficult to even begin thinking about addressing issues endemic to the profession at large. Not only is the profession driven by economic and social privilege, but architecture is still taught from a Eurocentric perspective, and BIPOC populations are under-represented among professionals, client groups and students. But changes are starting to happen. Several architectural institutions have begun seeking out more diverse critics and guest speakers, conversations are ensuing regarding curriculum shifts to include global and anti-colonial perspectives, and working groups have been formed to work towards equity among student bodies and teachers.

These are all important steps in the right direction, but in the frenzy of activity, there is a question that continues to stay with me: how can a profession which has for so long failed to address these issues so quickly shift its perspective to embody and enact meaningful change? This question brings to mind the words of American political activist Angela Davis: “I have a hard time accepting diversity as a synonym for justice. Diversity is a corporate strategy. It’s a strategy designed to ensure that the institution functions in the same way that it functioned before, except now that you have some black faces and brown faces. It’s a difference that doesn’t make a difference.”

Angela Davis’s poignant words point to a truth that we must confront which goes beyond institutional policy. We are tasked with a greater undertaking rooted in our shared humanity, and ultimately, how we choose to respond to human suffering. And if for a moment we lose our sense of how human a problem this is, we need only look back to last summer, to what ignited these movements.

Although this question extends far beyond the education and profession of architects, we are deeply implicated because architecture is fundamentally an expression of the human response to environment. If we—as architects, educators and students—are not invested in fostering an education that puts diversity, equity and inclusion at its core, how can we possibly design spaces that do the same? How can we possibly design for the increasingly complex social and environmental issues that we face? To confront these questions, we—as architects, educators and students—by virtue of each of these roles, are also activists.

While the protests in the streets of so many cities continued through the summer and fall of 2020, similar acts of protest filled the virtual spaces of architectural institutions across Canada. I attended a virtual all-school gathering at the University of Waterloo School of Architecture at the beginning of the summer term, where long-silent voices were heard for the first time. As a school, we shared a space where, despite the virtual setting, we were forced to embrace the difficulty, the discomfort, and the failure of the institution to address the concerns of individual students and long-standing issues around equity, diversity and inclusion. Brave individuals shared their encounters with racism and how these experiences affected them during their time in the field of architecture. Each person’s account was moving, eye-opening, and powerfully demonstrated the painful and long-lasting scars of injustice. Although others in attendance may have endured similar experiences, each person’s story was clearly important, and demonstrated that the healthy and resilient rebirth of our communities depends on every voice being witnessed and acknowledged.

Although architectural training is known to be broad, embracing so many emotionally difficult conversations, with their intense memories and powerful silences, was outside of my formal education. The work of addressing these issues felt radical because so much of institutional discourse on education focuses on externalities: the creation of policies, mandates, governances. Rarely do we look inward to the heart of the challenges at hand. Rarely do we look back at ourselves. The conversations we were beginning to have as a school revealed something absent in architectural discourse: humility, empathy, vulnerability and love.

Towards the end of 2020, I was asked to be an advisory board member for the University of Waterloo School of Architecture Racial Equity and Environmental Justice Task Force. In this position, I felt my primary contribution was to emphasize an overwhelming feeling of how much we have failed as a profession to see and tackle the issues of equity, diversity and inclusion. In board discussions, it was important for me to also recognize the longstanding efforts made by students at the University of Waterloo School of Architecture around these issues. Student-initiated groups such as On Empathy (est. 2014), Treaty Lands, Global Stories (est. 2016), and the Sustainability Collective (est. 2018) were perhaps small and largely unseen when they began, but these initiatives continue to demonstrate the profound and revitalizing role students play in the education and renewal of our institutions.

When asked to contribute to an article on dismantling racism in Canadian architecture schools, I was not sure I was the right person to take on the task. The genuine struggles and heartfelt efforts I have seen being made by students and faculty are not quantifiable. They are often embodied as complex and nuanced stories that contribute to the song we are collectively singing. I am humbled and inspired by the voices I have heard, and it is with great respect and reverence for each of these brave individuals with whom I’ve crossed paths that I found purpose to contribute to this work.

With each conversation at the University of Waterloo School of Architecture, and each initiative organized within architecture schools across Canada, it became more and more apparent to me that we need to take time to sit with questions before proposing solutions. The sense of urgency that emanates from every conversation may demand quick action. But to enact lasting measures, we must carefully balance the tension between moving forward to implement change with the slow work of nurturing each question—and one another.

The complexity of this undertaking is enormous, but every act of working together to build equity, diversity and inclusion is also an act of building trust, and in turn, building community—communities where it is necessary to continue asking the questions:

- Who do each of us need to become to embody the change we want to see?

- How do we traverse this difficult path together?

- And most importantly: How do we make sure that no one is left behind?

At every protest I attended last summer, there were moments where vibrant chanting gave way to a calm sense of strength and solidarity in one another. Musical instruments spontaneously appeared, and the passionate voices of protestors magically transformed into song. I was struck by the ability of a melody to hold both the ferocity of the protest and the vulnerability and tenderness of each individual. We were working in unison, and every voice was necessary. These are the moments that stay with me and inspire a way forward.

Jaliya Fonseka is an architectural designer and an adjunct professor at the University of Waterloo School of Architecture.

You may enjoy reading the companion piece to this article, From the Ground Up, by architect Anne Bordeleau, the O’Donovan Director of the School of Architecture at the University of Waterloo.