Book Review: Blueprint for a Hack

By Vikram Bhatt, David Harlander and Susane Havelka (Actar Publishers, 2020).

Blueprint for a Hack describes a five-day project that took place in 2017 in a village in the Nunavik region of northern Quebec. The Kuujjuaq Hackathon saw Inuit community members work alongside designers from southern Quebec, with the aim of examining and improving public spaces within Kuujjuaq, reducing landfill waste and participating in a cultural exchange.

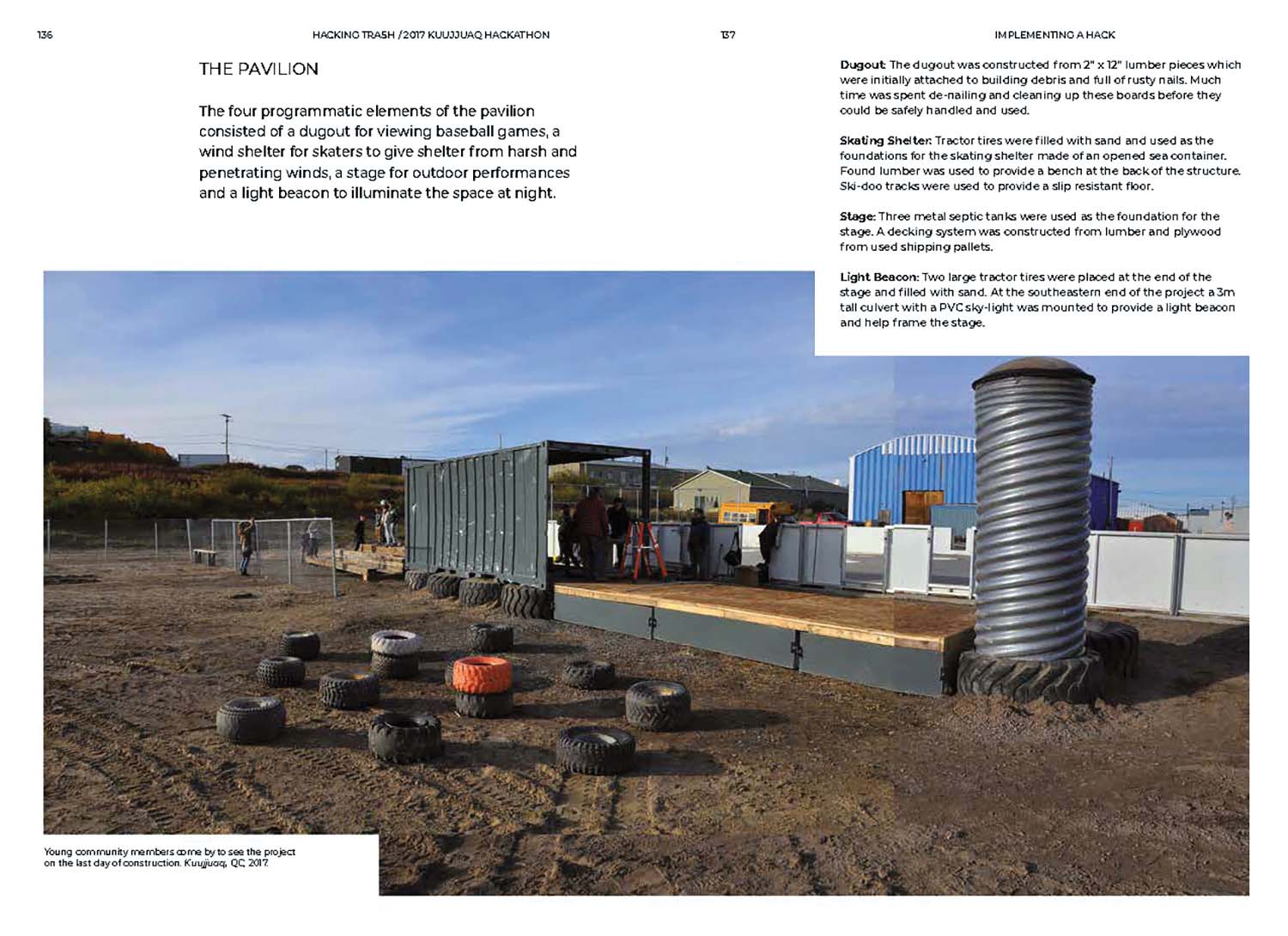

The Hackathon resulted in the construction of a community sports pavilion. Created with materials salvaged from the local landfill—a shipping container, scrap lumber, tractor tires and septic tanks—the pavilion, and the processes that shaped it, represent an unassuming yet critical precedent for challenging formalized practices of architecture and design. In recognition of this importance, it was awarded a National Urban Design Award in 2018.

As the book documenting the project explains, Canada’s arctic and sub-arctic communities are often shaped by forces that are ignorant of the cultural, environmental and logistical contexts particular to the north. This lack of awareness is evident in architectural and planning approaches that are typically informed by southern Canadian sensibilities and foisted upon remote communities with little meaningful consultation. This leads to underused projects that feel foreign and disconnected from their physical and social realities. A more effective approach would be informed by local engagement, Indigenous culture and lived knowledge of the challenges of remoteness and northern climates.

Historically, Inuit have long required resourcefulness. As nomadic peoples, they needed ingenuity to survive in the challenging environments of what would become Canada’s northern regions. This spirit continues to prevail as Inuit grapple with social and economic conditions arising from colonization and increasingly, the challenges of climate change. The resourcefulness at the core of Inuit culture—and the outward expression of this in informal building practices—has generally been overlooked by design practitioners. At the Kuujjuaq Hackathon, in contrast, this ingenuity was both acknowledged and honoured as a valuable source of information and as strategic inspiration.

Historically, Inuit have long required resourcefulness. As nomadic peoples, they needed ingenuity to survive in the challenging environments of what would become Canada’s northern regions. This spirit continues to prevail as Inuit grapple with social and economic conditions arising from colonization and increasingly, the challenges of climate change. The resourcefulness at the core of Inuit culture—and the outward expression of this in informal building practices—has generally been overlooked by design practitioners. At the Kuujjuaq Hackathon, in contrast, this ingenuity was both acknowledged and honoured as a valuable source of information and as strategic inspiration.

To “hack” is to modify and to work in new ways, and also to upend and challenge standard material applications and methods of production. The Hackathon aimed, in part, to learn from practices of “hacking” already present in modern Inuit life, and to apply a hacking mindset to improve public spaces in Kuujjuaq to better serve those who live there. This process included strategizing how to transform discarded waste into a useful construction.

Blueprint for a Hack argues that such informal invention and ingenuity may provide new routes forward for the disciplines of architecture and planning, and that these skills have potentially far-reaching implications.

The participatory design approach used in Kuujjuaq highlights a wider discussion that’s needed between architects, designers and planners about how knowledge is gathered and how spaces are designed. A more collaborative approach taps into deeper understandings of place and the history, people and interactions that shape it. The hacking mindset reduces waste and encourages active engagement of team members—both with and without formal design education—acknowledging the wisdom, creativity and resourcefulness of everyday locals.

Drawing inspiration from the ingenuity and resourcefulness of the Inuit serves as a valuable springboard for re-examining and re-imagining different ways of up-cycling materials—and for practicing architecture.

Review by Natalie Badenduck