All in it Together: mâmawêyatitân centre, Regina, Saskatchewan

ARCHITECT P3Architecture Partnership

In a marginalized Regina neighbourhood known as North Central, the contemporary mâmawêyatitân centre stands out amid the humble vinyl-sided and eroded clapboard houses. Mâmawêyatitân (roughly pronounced mama-WAH-yah-tin-tin) is a Cree word meaning “let’s be all together.” In this case, the moniker is quite literal: the building is a conflation of high school, daycare, community centre, library and satellite police station. It’s a weave of wildly variegated, potentially conflict-generating programs within a single complex—which is why its strategic design is so crucial to its success.

Designed by Regina-based P3Architecture Partnership (P3A) and funded jointly by the Regina Public Schools (Province of Saskatchewan), City of Regina and Regina Public Library, the mâmawêyatitân centre was completed in 2017 after a long process of negotiation and consensus building. First, the architects and other stakeholders had to establish trust and buy-in from community members, largely Indigenous and lower-income, who had a right to be skeptical. Aside from belonging to demographic groups that have been systematically marginalized, they had endured vague (and then broken) promises about the proposed centre since the idea was first discussed in 2001. By the time design development finally got underway, the program faced serious provincial funding cuts and had lost two major components—a health clinic and a food store—that were originally supposed to be embedded within it.

When construction started, the project extracted some harsh trade-offs: the new construction obliterated all the existing buildings on the site, including a century-old brick high school. That particular building was arguably of heritage value, but also carried an unfortunate visual evocation of residential schools for its mostly Indigenous student body. The existing community centre, of more recent vintage, also had to be demolished in order to construct the new unified, multi-programmed building.

The centre aims to embody Indigenous principles in its materiality, by abstracting the Prairie locale’s wide horizons in its opaque sky-blue glass and Tyndall-stone base. “The building is about the place itself, but also everyone’s experience of the place,” says P3A principal James Youck.

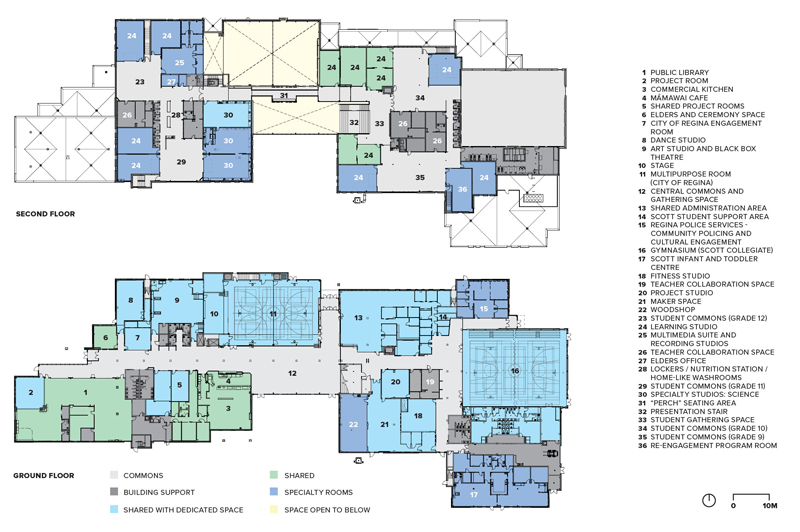

In its programming, the centre goes far beyond the typical multifunctional building, where different users have separated zones, or distinct groups use a facility on weekdays and on weekends. The logistics of creating a deeply integrated space—that is, space that can instantly or in some cases simultaneously serve multiple purposes—required much research and many conversations.

The high school, for instance, needed to access the commercial kitchen, workshop, art studio, theatre and library—all spaces which would be available for community use as well. And yet certain zones—the after-school hangout room, councillor’s office, daycare (devoted strictly to students’ children) and faculty quarters—would be accessible only to the high school students and staff. The central administrative and reception area would be partially shared, partially integrated; that is, city and school staff would have their own specifically designated work stations, but both would share office supplies and equipment anchored in a back room.

The architects collaborated with the usual gaggle of government bureaucrats, but also with local residents and Indigenous Elders. The latter advised on everything from colours to the particular placement of the Elders and Ceremony Space, which they directed the architects to position prominently beside the main community entrance.

Walking through the mâmawêyatitân centre, I’m struck most of all by the deceptively complex floor plan. I say “deceptively” because on entering the building, it reads like a fairly standard (and slightly corporate) building. But a close analysis of the ingress and egress points, and the placement of the various multipurpose rooms bespeaks a highly strategic Rubik’s cube of transformable and interactive spaces. There are no demarcation lines between user groups; instead, spaces seep or surge into one another. Certain rooms, like the workshop and commercial-grade kitchen, serve different end users once the school day ends, and they are designed with embedded moveable walls to expand, contract and secure the spaces as needed. Other areas, like the library and the commons area, serve different user groups simultaneously. (The library is open to the public throughout the day, when it’s also used by students.) These zones have a different spatial strategy.

Architecturally speaking, each of these spaces is “non-binary,” as it were, projecting an identity like a hologram projects an image that is ever-changing as the viewer shifts position. The central commons area, for instance, reads much like a traditional community centre lobby when one approaches it from the building’s main public entrance. But from atop the bleacher steps of the second-storey high school zone, one’s view focuses on an installation of suspended bicycles hanging from the ceiling of the commons. It’s a youth-centric gesture that seems to “belong” to the high school while not seeming out of place for the larger community.

In the middle of the building is the largest space: the main multipurpose room, overseen and used mostly by the City of Regina as a community gymnasium. For performances and larger events, it can be rendered even larger by activating the attached stage and opening the room’s folding glazed doors to let it spill into the commons. The commons, in turn, opens onto the rear outdoor space, landscaped with Indigenous-inspired plantings. A rather stark paved area between the building and the landscaped zone was designed to be screened and visually enriched by a wood pergola, which has not yet been realized due to budget cuts during design development.

Be advised that the architectural firm’s name—derived from its earlier iteration as Pettick Phillips Partners Architects—bears no relationship to the notorious development process known as “P3”. And for sure, it would have been challenging—maybe impossible—to pull off a project with this degree of foresight and inclusivity under the standard P3 process, which blindly favours the immediate cost cut over the qualitative benefit. So much daylighting, so many entrances and exits? Not strictly necessary on a blindly functional basis, and yet crucial to delivering efficient, secure multipurpose programming. The building’s generous glazing and multiple access points allow users to instantly see if, when and how a space is occupied from their dedicated ingress point. For the neighbourhood outside, the transparency of the highly activated building also ensures that Jane Jacobs’s “eyes on the street” are present for the neighbourhood.

A thoughtful attention to spatial occupation and sightlines plays out throughout the building. Both the daycare and the satellite police station are tucked discreetly out of the sightlines of the high school entry zone—close by, but not overtly in the face of the students. The high school’s student washrooms are designed as a panoply of separate single-user rooms, rather than the near-universal communal washrooms. That strategy—though a little more costly in terms of space and dollars—avoids creating one of the most fertile grounds for bullying in a school.

Two years after completion, how is the approach of being “all together” working out? Inside and out, the structure still looks pristine, with virtually no traces of vandalism. That attests to its acceptance and embrace by the community, says Youck. But he also notes that the acceptance was hard won, and is an ongoing, ever-renewing process. An outdoor pergola, if and when it receives funding, will add much-needed organic warmth and a brise-soleil to the rear area. The centre’s highly flexible common spaces do allow for an informal pop-up grocery and periodic visits by a mobile health unit, but the loss of the on-site health clinic and food store remains Youck’s biggest disappointment about the project.

Both the architects and the community are cognizant of the need for more services, more resources and more time to overcome the disadvantages of long-standing marginalization, says Youck. The mâmawêyatitân centre is designed to facilitate this restorative process during adolescence and beyond. But Youck himself acknowledges that it will take years to know the true measure of the success for the building. “It’s really the next generation where we’ll see this come to full fruition.”

Adele Weder is an architectural curator and critic based in British Columbia.

CLIENT City of Regina, Regina Public Schools and Regina Public Library | ARCHITECT TEAM Chris Roszell (MRAIC), James Youck (MRAIC), Brenda-Dale McLean (MRAIC), Sherry Hastings, Nitish Joshi, Ashton Fraess, Rebecca Henricksen, Deb Christie | STRUCTURAL JC Kenyon Enegineering | MECHANICAL MacPherson Engineering | ELECTRICAL ALFA Engineering | CIVIL Associated Engineering | LANDSCAPE Crosby Hanna & Associates | INTERIORS P3Architecture Partnership | KITCHEN Burnstad Consulting | COST BTY Group | LEED/COMMISSIONING MMM (now WSP) | CONTRACTOR Quorex Construction Services | AREA 10,500 m2 | BUDGET $32 M | COMPLETION September 2017