Think Tank: Stanley A. Milner Library Renewal, Edmonton, Alberta

PROJECT Stanley A. Milner Library Renewal, Edmonton, Alberta

ARCHITECTS Teeple Architects (Design Architect) with Stantec (Architect of Record, formerly Architecture | Tkalcic Bengert)

TEXT Trevor Boddy

PHOTOS Andrew Latreille

After nearly a decade of design and construction, the Stanley A. Milner main branch of the Edmonton Public Library, by Teeple Architects in association with Stantec, finally opened last September, with pandemic precautions in place. One of our few major public buildings to open in 2020, the design may also be Canada’s truest indicator of where library architecture is headed. The direction it proposes, though, may not please fans of heroic made-from-scratch architecture, or for that matter, books. Here is my explanation of this unsettling conjunction.

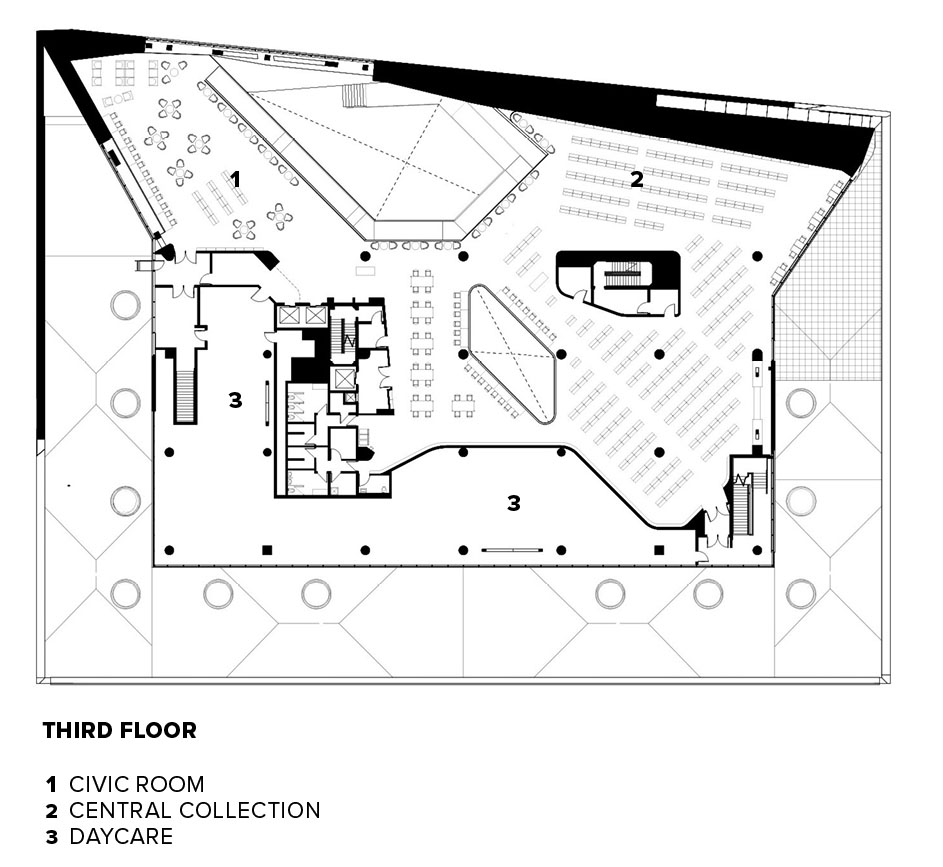

Unlike other major downtown central library designs in Canada, the reopened Stanley A. Milner is a revamp of an existing structure, rather than a new build. And yet, its contents are a far cry from its predecessor. A large part of its second floor is devoted to makerspaces: a digital milling and printing lab; textile layout zones; sound recording and mixing studios; e-sports lounges; a teaching kitchen; video editing suites, and so on. Yes, there are rows of book stacks outside these, but the gathered machines are clearly the stars of this show. They’re swamped by eager young users after school ever since opening, many of them previously reluctant to darken the door of any library, and unable to afford even the most basic of this suite of largely digital tools. Moreover, there is a new breed of librarian at the ready to assist them, helping patrons operate the machines, locate online sources for ideas, and occasionally even suggesting references from a pulp-and-paper database—that is to say, a book!

As an Edmonton teenager who made a weekly pilgrimage to what was then called the Centennial Library, I would have been delighted with the prospect of this range of machines and minders to learn from. Lest I be typed as some dusty “keeper of the books,” one of the main reasons for my Saturday trips was the Centennial Library’s huge lending library of vinyl LPs, one of the largest on the continent. I loaded up every week with King Crimson, Thelonious Monk, Richard Thompson and my other faves. The building encouraged lingering with plush carpets, skylights and what had to be the first Barcelona Chairs in any Alberta public building—rehabilitated, they are still in use in the updated building.

Back then, the Edmonton Public Library was advanced in its embrace of technology and a social mission to spread knowledge to all citizens. It remains so today—their system was named “Best in North America” by Library Journal in 2014. I have no doubt that the tech-driven knowledge on offer to anyone with an Edmonton library card will spark careers for talented future designers—if there is to be an Alberta post-oil creative economy, it will be more likely born at the Milner Library than in any legislative corridor. Moreover, as a profession, architects hardly need convincing that knowledge can be created and transmitted in the form of materials, not just through words on a page. Our design schools talked a lot about phenomenology during the 1990s, but this new shift from passive reading to embodied activity marks a significant change. The maker-centric approach may be at the vanguard of larger changes in libraries, too. Raymond Moriyama’s 1969 Ontario Science Centre inspired experience-based, populist science museums around the world. In a similar way, the new Edmonton building—along with other projects of its type, such as RDHA’s Old Post Office in Cambridge, Ontario—could be signposts for a shift to experience-based large public facilities. A new word may be needed for buildings like this, instead of “library.” Time to bring back Buckminster Fuller’s “sensorium”?

The new Stanley A. Milner library is the product of two powerful and relentless personalities—Toronto architect Stephen Teeple and Edmonton Public Libraries CEO Pilar Martinez. Their collaboration began almost a decade ago, when Edmonton’s City Architect, Carol Belanger, catalyzed the choice of Teeple’s firm for what was initially thought to be merely a re-skinning of the 1967 building, designed by Fred Minsos. The Centennial Library was a graceful modernist-classical pavilion, disfigured by a gawky 1999 PoMo addition on its Churchill Square elevation. When design started for Teeple and associate architect Stantec, Martinez was a senior librarian on the building committee. As the project progressed from technical and program evaluation, through budget cutbacks and changes of government, she was eventually appointed to the top job—in large part to get the project done. Teeple had designed the immense Clareview Recreation Centre in northeast Edmonton, which included a large branch library, earning the firm points with clients at city hall and at Edmonton Public Libraries. Indicating how much things have changed in but a few years, that branch did not feature a single makerspace gizmo when it opened in 2014.

Like many other tendencies in Canadian public buildings, rethought downtown libraries here begin with a Raymond Moriyama and Ted Teshima design, the 1977 Toronto Reference Library, with its generous light and atrium. The next major downtown libraries are a mixed pair: Moshe Safdie’s popular/populist Vancouver Library Square, compelled by a shopping mall public vote to Colosseum-imagism; and the Patkau’s Grande Bibliothèque de Montreal (completed with Menkès Shooner Dagenais Le Tourneux and Croft Pelletier), a fine design bedevilled by technical issues. Schmidt Hammer Lassen and Fowler Baud & Mitchell’s Halifax Public Library was one of the first, and likely best transmission to Canada of the Nordic massing gimmick of displaced cantilevered boxes. The crown of the latest run of central libraries in Canada is Snøhetta and DIALOG’s Calgary Public Library, achieved with top drawer Nordic hutzpah, resulting in a rounded volume hovering over an active LRT line. Warmly finished and filled with light, it shone as a venue for a 2019 David Adjaye public talk I attended. The all-new Calgary library and the radically renovated library in Edmonton both have a similar floor area, at approximately 22,000 square metres and 15,000 square metres respectively. However, at $245 million, the Calgary library budget was nearly three times the $84.5-milllion cost of the Stanley Milner Library.

Armed with facts like this stark contrast between Calgary and Edmonton construction budgets, architects need to be increasingly skeptical whenever they hear claims that renovating an old building would cost more than building anew. After much discussion about demolition and a re-start de novo, the Edmonton clients and design team decided to remove all exterior windows and walls, while conserving the 1967 building’s concrete frame right down to the parking garage and foundations below. The finished design retains existing floors, elevator shafts, even escalator and skylight locales, plus much of the existing mechanical system. On the Churchill Square side, the library is expanded and wrapped with a new high-performance envelope. (Overall, the building attains LEED Silver.) There is no doubt that the interior finishes are banal, and the rhomboid zinc-clad exterior overexuberant. That said, with its programmatic tilt to makerspaces, its extreme parsimony with public funds, and the embodied energy conserved by recycling much of the old library, Edmonton’s example is much more the library of the future than Calgary’s, which history may soon regard as the extravagant final creation of that city’s greatest building boom.

As the gun-metal grey Azengar zinc panel cladding started to be installed during late construction in 2019, a rare-in-Canada public debate about design erupted, ignited by a critical broadside from Edmonton Journal columnist David Staples. Television and social media soon chimed in, bringing with it a battle of metaphors, with hundreds of online speculations as to whether Teeple’s chamfered and faceted metallic design more resembled a Star Wars galactic cruiser or an Eastern Bloc tank. Martinez and her team realized they could not win against this type of media frenzy, so wisely turned it on its head. With cheeky advertisements and a social media handle of #THINKTANK, Edmonton’s clever librarians gave as good as they got. “The building opens up curiosity,” says Martinez, concluding that Teeple’s design is “a phenomenal space to inspire learning creativity and imagination.”

The renovated library clearly draws inspiration from the aggressively angled massing of OMA’s 2004 Seattle Public Library. The most striking interior space of the #THINKTANK is its splayed and splined atrium, new construction pushed out along a narrow zone in front of the Centennial Library’s structure. The addition forms a better locale of orientation and entry than any space in Koolhaas’ design. Fast + Epp engineers were charged to find a way to hang the addition’s structure off the existing building’s frame and foundations, resulting in one of the building’s visual highlights—a storey-high truss exploding out of the most acute-angled corner and set on elegant Y-frame columns, their engineering logic vitalizing the entire room. However, this atrium that is so heroic up top comes with a distraction at its bottom, in the form of a storey-high interactive video screen—a digital embellishment at architectural scale.

When I returned a few weeks after the press preview to see the library in public use, that big screen was tuned dully to an educational television station, with noone watching anywhere along the ramps, balconies and gathering zones of the atrium. The questionability of the trying-too-hard populism of this mega-screen was doubled by the adjacent super-graphic designed by library staff (not Teeple’s office) proclaiming “IMAGINE” in six-foot-high cut-out letters. I cannot think of anything less likely to inspire my mind to ‘imagine’ than a big sign ordering me to do so, with a TV running mindlessly next to it, as in pandemic living rooms. Similarly oversized, multicoloured letters are installed in corridors outside the basement public meeting rooms. Likely, library staff have overreacted to the public critique of the sterility and monochromia of Teeple’s design. When visiting, look up from there to enjoy the atrium and its inspiring conjunction of Teeple’s spatial legerdemain, Fast + Epp’s structural brilliance, plus Things I Knew to be True, Peter von Tiesenhausen’s wall-mounted public art at top—consisting of various figure-like recycled steel elements, grouped into glyphic ‘words’ and ‘sentences.’

.

The architecture of the Stanley A. Milner Library is perhaps blunt and forcefully ungainly—but then again, these qualities are often thought to be virtues by the Prairie psyche—hey, they propel us through those snowdrifts! With huge oil refinery and petro-chemical complexes clearly visible to the east from downtown, a metallic palette makes sense in Edmonton. The provincial mammal may be the bighorn sheep, but the animals closest to the Albertan soul are the larger-than-life dinosaurs. Indeed, the architecture surrounding Sir Winston Churchill Square is the most diverse single collection of large buildings after modernism in our nation—a heroic dinosaur park for the architectural ideas of the past half century, even more interesting in its agglomeration than in its individual pieces. There is the triceratops of the voluptuous corner curves of the Art Gallery of Alberta, the late Randall Stout’s homage to former employer Frank Gehry. There is the Edmontosaurus of the Kahn-inflected City Hall by Gene Dub. Skidmore Owings & Merrill’s Edmonton Centre is the brontosaurus of the bunch, and the glassy wings of Diamond and Myers’ original Citadel Theatre take flight as a pterodactyl. Not surprising—because it comes from the talent who designed a fine Alberta museum for thunder-lizards—Stephen Teeple’s latest addition, a well-armoured and bold stegosaurus, fits right in.

Trevor Boddy (FRAIC) recently co-wrote and produced, with Barry Johns (FRAIC), a 30-minute video on a 1962 “missing minor masterpiece” by Arthur Erickson, located outside Edmonton. The Dyde House and Garden is being presented in virtual screenings with live commentary at architecture schools and professional associations in 2021.

CLIENT City of Edmonton; Edmonton Public Library | ARCHITECT TEAM Teeple Architects—Stephen Teeple (FRAIC), Richard Lai, Christian Joakim, Avery Guthrie (MRAIC), Omar Aljebouri, Will Elsworthy, Mahsa Majidian (MRAIC), James Janzer, Rob Cheung, Petra Bogias, Tomer Diamant, Sahel Tahvildari, Julie Jira, Tara Selvaraj, Dhroov Patel, Fadi Salib, Eric Boelling, Marine de Carbonnieres, Ali Aurangozeb. Stantec / Architecture | Tkalcic Bengert—Brian Bengert, Dawna Moen, Kristi Olson, Shaune Smith, Ian Colville, Carol Regino, Alyssa Haas, Derrik Kennedy, Ana Borovac, Ben Brackett, Joseph Chan, Ted Fast, Erika Hostede, Matt Roper, Bryanne Larsen, Taylor Bengert | STRUCTURAL Fast & Epp | MECHANICAL Arrow Engineering | ELECTRICAL AECOM | LANDSCAPE Scatliff+ Miller+Murray | INTERIORS Teeple Architects | CONTRACTOR Clark Builders | CIVIL AECOM | FAÇADE RJC | LEED WSP (Formerly Enermodal) | ACOUSTICS SLR Consulting (Canada) | ENVIRONMENTAL Gradient Wind | TRANSPORTATION Vinspec | CODE Kim Karn Consulting | AREA 15,326 m2 | BUDGET $84.5 M | COMPLETION September 2020

ENERGY USE INTENSITY (PROJECTED) 120 ekWh/m2/year | BENCHMARK (NRCAN 2014, non-healthcare institutional buildings after 2010) 278 kWh/m2/year | WATER USE INTENSITY (PROJECTED) 0.1186 m3/m2/year | BENCHMARK (REALPAC 2011) 0.98 m3/m2/year