Practice: Procuring Change

How can current RFP processes be improved to yield better outcomes—both for architecture and for architects?

When emerging architecture firms begin to scale up to larger projects, it often means plunging into the world of publicly posted Requests for Proposals (RFPs). These competitions are a requirement for organizations in the public sector, as a means of ensuring fairness and transparency on taxpayer-backed projects. They are also used by a broad range of client types to find architects for important buildings—hospitals, schools, civic centres, academic buildings, museums, and libraries—to name only a few.

For somebody looking through the list of interested firms for any significantly sized RFP, the globalized nature of architecture as a business becomes clear very quickly. Large firms from urban centres all over Canada are usually interested, and it is not uncommon to also see firms from the United States and overseas. No matter who you are, to participate in this process on multi-million-dollar budgeted projects likely means to compete with behemoths—firms staffed with hundreds of people, equipped with multi-person marketing teams and with portfolios that span the globe.

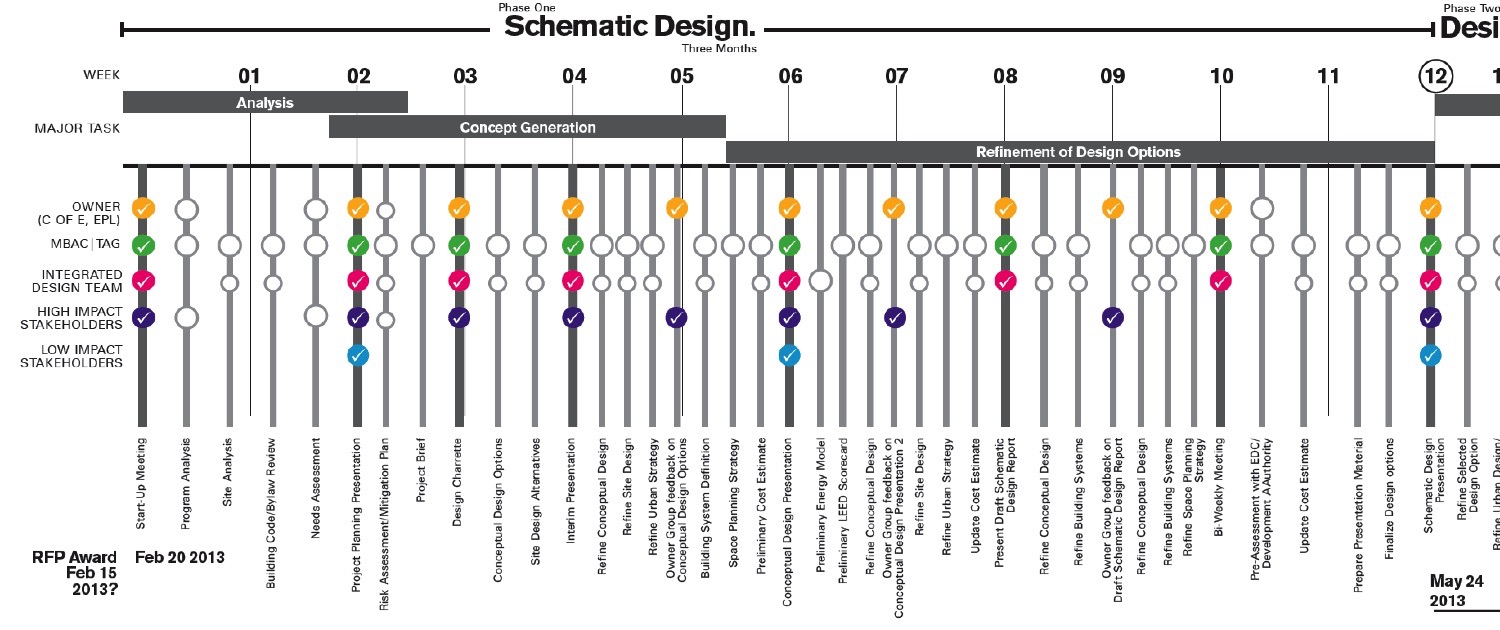

To say the workload these pursuits place on the industry is “burdensome” would be a serious understatement. The procurement phase for larger-scale projects is often a months-long, multi-phased affair. A qualifying round can see as many as 50 different firms submitting for the project: imagine a 20-page limit on qualifying submissions, and then imagine 1,000+ pages pouring onto a client’s desk at one minute before deadline. Weeks later, a smaller number of firms then pre-qualify for a more labour-intensive second round. Then there might be interviews. There could be travel involved at every step. The work involved for everybody is tremendous and it costs a lot of money. You may also be asked to provide services well outside of typical architectural scope.

If you choose to chase an RFP, the statistical likelihood is that you will lose. Lose early in the process, and you feel personally hurt that you did not make the cut. Lose late, and you may have spent thousands of dollars on a fruitless pursuit. Then there is the debrief process, where you may learn that the person evaluating submissions knows little about architecture and misunderstood something critical about your submission. The successful candidate goes on to design a building that stands as a monument to the time you failed. There is more than one of these monuments in your city. You may pass by a couple on your way to work.

The raw workload—all of it overhead—can prove prohibitive, especially for smaller firms. Yet despite all this genuine pain, the procurement process is an important means of access for designing some stellar projects and (critically) for meeting new clients.

Toon Dreessen is founder of Ottawa-based Architects DCA, a past president of the Ontario Association of Architects (OAA), and an outspoken advocate for changing procurement practices for architecture in Canada. He thinks that current procurement practices are “fundamentally broken.” “This is really a matter of public interest,” says Dreessen. “Unfair procurement processes harm small businesses, and their negative impact on the built environment lasts for generations. That’s something that the public needs to better understand.”

Dreessen has a long list of issues with procurement practices. Among them: he believes that they remove dialogue between clients and prospective architects that would improve projects, they inherently skew in favour of larger firms, they stifle innovation by keeping people from asking questions (lest they lose a competitive advantage), and they ultimately create a focus on low fees that has become so prevalent that it is damaging Canada’s architecture. Asked if there was one thing he feels it is important for procurement professionals to understand, he says: “Ultimately fees don’t matter. We spend too much time and effort arguing about fees, when we really need to be arguing about quality.“

Dreessen noted that most architecture firms in Ontario are small, with only one licensed architect. “These firms don’t participate in this public procurement process because they can’t. They can’t get their foot in the door […] They can’t win these big projects, and when I talk about big projects, I’m talking about a ten, fifteen, twenty-million-dollar project. That’s totally manageable by a small firm of five people.”

“That means that really big firms are the only ones left at the table, and they’re fighting to get even those relatively small projects, let alone the huge ones.”

Dreessen has argued for design competitions as a better approach, saying that they provide a place to foster innovation and for firms to stand on the strength of their ideas. They likewise offer a chance for even the losers to grow their portfolio. Dreessen has also advocated for more quality-based evaluation, as opposed to evaluation based on fee. He suggests that procurement needs to remain fair, while also making room for “conversation” between architect and client.

“If we agreed on fairness—and the concept of fairness—we wouldn’t have fee-based RFPs. We would agree on what a fair fee is, and we would agree on what a reasonable compensation is, and we wouldn’t leave it to a race to the bottom,” says Dreessen. “If all things are equal, it should be a meritocracy. It should be that the person who gets the job is the best qualified for it, or has the most creative solution in a competition format. That should be the deciding factor.”

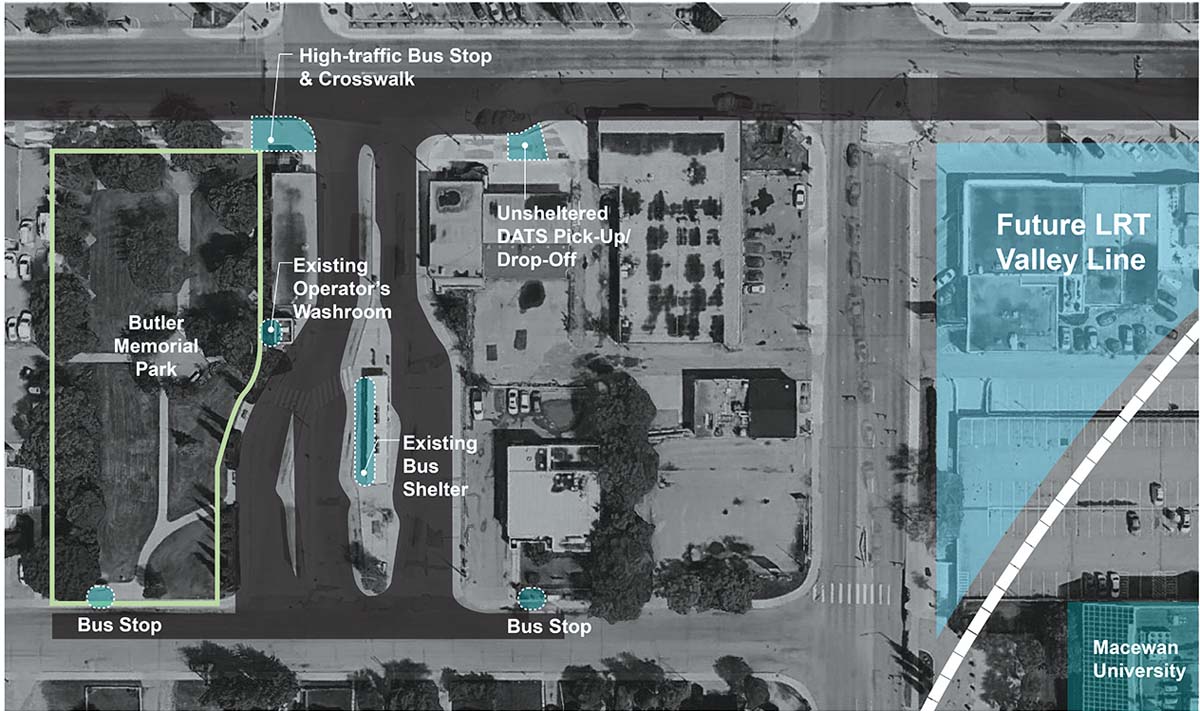

Others in Canada have even gone so far as to implement a different approach to procurement for architectural services. The City of Edmonton stands out as a case study—not just because of their unique practices, but because of the design-minded politics that led them there. In 2005, Edmonton’s then-mayor Stephen Mandel famously said in a state-of-the-city address: “The time has passed when square boxes with minimal features and lame landscaping are acceptable. Our tolerance for crap is now zero.”

Since that time, Edmonton has become more and more quality-minded in how it evaluates architects submitting proposals to design City projects. It is also unique in having a City Architect on staff. For the past decade and a half, Carol Bélanger has worked to refine Edmonton’s procurement practices for architectural services. “At the time I started my position, we used to do ‘call-ups’, but these were by invitation only,” says Bélanger. “So, you would call up three firms or four firms, to be ‘competitive.’ It was limited by who you knew.”

Influenced by provincial trade agreements that required more projects to be put out for public bid—as well as by the publicly stated desire to do away with “crap”—the City changed how it evaluated architects submitting to design its larger projects. It eventually moved to a two-phased submission and evaluation process. The first is a qualifying phase to create a shortlist of architects identified as being able to complete the work; the second phase consists of an RFP process for these pre-qualified candidates, as well as an interview for finalists. This process was designed to limit the raw work of proposal-writing on the industry at large, while still having an RFP process that focussed—in detail—on the project at hand.

“Once they know they are shortlisted, then we can put out the full-blown RFP,” says Bélanger, adding that the second phase of Edmonton’s RFP process includes the pre-qualified candidates’ vision for the project. “We ask for a vision. Not a design, but a vision: from an urban design point of view, how would you meet this context?”

Perhaps most importantly, Edmonton changed how they evaluated architectural fees. The fee component of their RFP process is rated as 10% of the overall scoring for the submission—very low compared to other governments and public agencies, who often rate fees at 30% or more of a total RFP score. Moreover, the City also works according to fee recommendations established by the province’s professional associations, the Alberta Association of Architects and the Consulting Architects of Alberta. This has the effect of making the expected fee for the project clear to all potential submitters from the outset, and already in-line with professional expectations for what is necessary to deliver good work.

“We’re not allowing firms to ‘buy’ the work with a low fee. But at the same time, being in a municipality, we’re still cognizant of having a limited budget. We’re not just going to pay exorbitant fees,” says Bélanger. “For the most part, unless somebody misunderstands something, we’ve always seen people get full marks on the core fee.”

What has followed from these changes? “The outcome has been nothing short of amazing,” says Bélanger. City of Edmonton projects have been celebrated with four RAIC Governor General’s Awards since 2018: achieved for Borden Park Natural Swimming Pool, The Real Time Control Building #3, Borden Park Pavilion (all by gh3*), and the South Haven Centre for Remembrance (by SHAPE Architecture with PECHET Studio and Group 2 Architects). Says Bélanger, “We’re not doing the work for awards, but the awards are a good indicator from a design excellence perspective.”

Public reception to the projects has also been positive, says Bélanger, noting that memberships to related civic organizations are up. The new buildings show up regularly on social media. It is even an issue which has been put on the ballot in Edmonton’s 2013 civic election: one mayoral candidate decried “Taj Mahal” rec centres, and garnered relatively little support. It turns out people liked design-forward civic buildings and saw the value in what the City was doing. Mandel and Bélanger both earn mention in the book Canadian Modern Architecture, 1967 to the present, with educator Graham Livesey writing that they sparked an “architectural renaissance” with their procurement practices, resulting in “a spectacular series of public projects, mainly by out-of-province firms.”

It is worth examining procurement carefully if an “architectural renaissance” that is also popular with the public can stem from changes to a city’s RFP practices.

There is a lot that RFPs determine before proposals are submitted. In the process of creating an RFP, potential clients of architects—often the staff of public agencies—determine criteria from the outset for who can bid on their projects. This entails making value judgements about what is important in designing the potential building, and what type of architect will be the best choice to design the project. Often, a culture of risk aversion creates a preference for firms who have done similar work in the past: much of the time, you can’t apply to design a building like a library if you haven’t already designed some pre-determined number of them. There is also the issue of how design teams are evaluated, and who does the evaluation. To what extent do client representatives understand architecture? To what extent should they?

Asked about issues with RFPs and procurement, the OAA responded with a written statement, including the following: “Among the most common issues are requirements that do not reflect a correct understanding of the Architect or Licensed Technologist OAA’s role, resulting in OAA members being expected to take on tasks that are the responsibility of others. The result might mean an architect finding themselves responsible for activities and outcomes they do not control, including the performance or responsibilities of the client, authorities having jurisdiction, or the contractor.”

There are other important issues beyond sorting out who-does-what. “This lack of understanding can also impact how to design an appropriate evaluation tool / criteria for selecting the right professional for the particular project you may have.” The OAA’s statement also raised issues of RFPs that include work impossible to cover under mandatory professional insurance.

The OAA advocates for Qualifications-Based Selection (QBS), which recommends that clients select the most qualified firm to design the work and negotiate a fee afterwards. The OAA website likens the process to a company hiring a new staff member first, and then negotiating their salary after. This approach differs from the City of Edmonton’s, but it is still a step outside of the norm for most public RFP requirements, which require a fee to be declared as part of the submission process. The matter of how—and when—architectural fees are decided has serious implications for how much the architect eventually gets paid. That, in turn, impacts the scope of service that an architect can reasonably deliver, while still surviving as a business.

Every facet of procurement invites questions with complex answers, and the processes by which we buy something are intimately connected with the product we receive. In the case of architecture, the product being purchased carries long-term planning implications and large environmental impacts, and it informs the look and function of the buildings we use every day. It is critical for potential clients to take time for interrogation, education, and introspection in their approach.

Jake Nicholson is a writer based in London, Ontario, with extensive experience working on proposals for architectural and engineering firms.