Build it and they will come: Bringing small house to the Canadian long-term care sector

Building (and thinking) big can allow us to 'live small' as we age.

If there was any doubt as to the role the built environment plays in safeguarding public health, it’s surely been erased by now. Over the last two years, Canadians from coast to coast witnessed the devastating effects of ill-considered design regulations and a lack of building intelligence in residential eldercare facilities.

The state of long-term care today is a direct result of its troublesome history and perpetual marginalization in policy making, in mainstream healthcare, and certainly in design discourse.

This is not to throw our profession under the proverbial bus; many if not most architects have shifted from a pathogenic thinking to a salutogenic thinking in long-term care, designing homes that privilege the privacy, dignity, and wellbeing of residents.

But these homes have also been tethered by a compliance mindset driven (in Ontario at least) by the systems and standards that have governed the design, development, and operations of long-term care homes since the late 90s.

At Montgomery Sisam, we’ve always been at the forefront seniors supportive housing. Working with many of the most progressive thinkers and doers in the industry, our practice has been a proud partner to the quiet revolution in long-term care design.

Now, in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, it behoves us to become not just passive allies but vocal advocates for more progressive, evidence-based models of care. One among many such model is small home.

Small home addresses many top-of-mind issues in long-term care today

The concept is simple. Small homes are designed to be intimate, residentially scaled facilities with accommodations for a very limited number of residents, usually 8 to 12. Each resident has their own private space, and access to a shared living room, family kitchen and outdoor space, all of which are home-like, elder-friendly, and easy to navigate. And resident support is provided by multi-skilled workers responsible for cooking, cleaning, and caregiving.

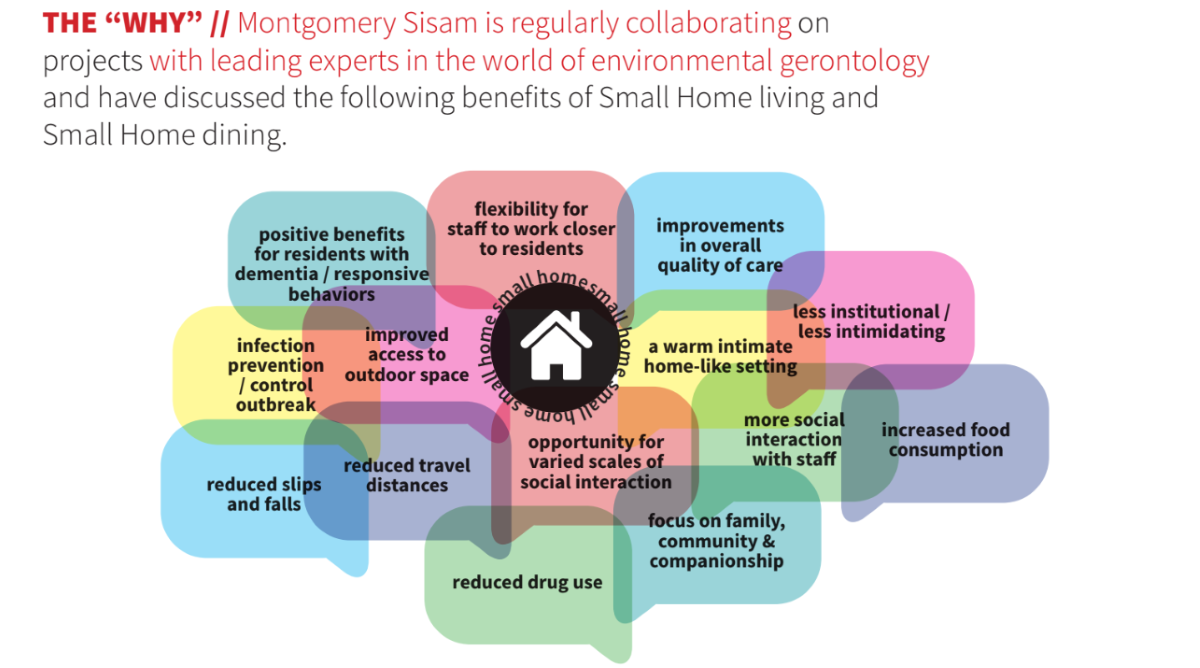

Small home design has many proven merits. Their intimate physical environment and operational structure privileges resident-caregiver relationships, social connectedness and a more familiar, more familial living and dining experiences [1]. What’s more, the compact, intelligible nature of a small home floor plan aids in wayfinding, fall prevention and staff workflow [2]. And the self sufficiency of each home along with their limited number of residents lends itself to better infection prevention and control and natural cohorting during an outbreak [3].

Now, small home is by no means new to residential long-term care. Its origins can be traced back to the Green House model in the United States and similar projects around the globe [4]. It is, however, a challenging pursuit in Canada where the current climate favours larger, leaner buildings.

Lean design aims to create the most effective buildings possible with the least amount of square footage. It allows architects to meet legislated standards while eliminating redundancies and optimizing the floor plan to help providers manage the effects of strict funding structures, rising capitals costs and major staffing shortages. And, when coupled with other important design qualities, it offers a sustainable balance between efficiency and experience for safe, healthy, dignified elder-friendly residences.

The thing is these larger, leaner buildings simply don’t compute with our post-pandemic consciousness and the growing research favouring small living.

So, how do we get the benefits of small home while maintaining the same operational integrity?

We recalibrate our priorities. We find a better balance between experience and efficiency. We build big to live small.

It starts with shifting our thinking from the macro to the micro, understanding the granularity of users’ day-to-day experiences and mapping out every decision in the context of resident life and staff workflows.

Next, we have to embrace the operational differences that comes with this thinking, scaling down the traditional 32-bed Resident Home Area (RHA) as much as possible into smaller subclusters of interconnected, self-contained units with a limited number of bedrooms. Any degree of ‘smaller’ is better in the pursuit of living small.

Then, we have to fight the lure of centralized services and create, in each of these clusters, a strong social heart complete with an open family-style kitchen, dining room, and den-like living area and we have to couple this social heart with accessible, purposeful outdoor space.

Finally, we have to strategically and mindfully connect subclusters to a central service hub to achieve the essential efficiencies that come from a larger care structure.

In the build big, live small model, every element related to the resident experience, from the hearth to the table to the garden, is scaled down to recreate the comfort and intimacy of home and day-to-day living. As evidenced by small house research, it has the capacity to yield tremendous gains, including improvements in the overall delivery and quality of care [5]; improved relationships between residents and staff [6]; lower incident rates [6] and higher resident satisfaction and self-reported wellbeing [7]; and increased staff recruitment, retention, and satisfaction [8, 9]; and, in all of these things, a higher quality of life for residents. What’s more these gains exist within a larger building structure so as not to impact the efficiencies of its back-of-house operations.

If it’s that easy why isn’t everyone already doing it?

Systemic challenges in long-term care development persist, aggravated in recent months by supply chain issues, excruciating inflation, and the scarcity of trades.

You cannot operate the build big, live small model for the same cost as a traditional home. Subclustering resident homes areas requires duplicating some program elements, and duplication requires more money and more staff, inherently working against lean design gains from a tighter floor plan and smaller square footage.

Moreover, build big, live small isn’t just a design approach but a model of care, one that requires a fundamentally different philosophical outlook at every organizational level to be successful. And in the wake of the pandemic, staff morale is low and staffing shortages persist.

But a radical culture change is possible; the willingness is there, and financial help is coming with more investment being made in the long-term care sector than every before. We can only hope that with the promise of a better future, the workforce will come and come inspired.

So, what’s the takeaway?

We are at crossroads.

Residential long-term care in Canada has and continues to suffer from many competing challenges. In response to the public and political awakening to these challenges, a new national standard is set to be released. But standards traditionally limit lateral thinking. And those of us who have been working in this sector for years know compliance isn’t the answer here. Creativity is.

The build big, live small model is one way to incite real, substantive change now.

Building big to live small, however, is not without its challenges. It relies heavily on the human factor, from financiers to the front lines. In such a politically charged atmosphere, where many discussions and decisions are dominated by dollars and cents, it is our professional responsibility to advocate for these evidence-based design solutions, how they can be implemented, and the policy alternatives needed to support them.

With a more forward-thinking dialogue in place, organization-led innovation and sector-wide transformation becomes not only possible but achievable. What follows will chart the course of history for generations to come.

Alexandra Boissonneault, Associate, Research and Communications & Tony Ross, Principal Montgomery Sisam Architects