Interview: Nina-Marie Lister

Ecological designer and registered professional planner Nina-Marie Lister’s work spans between policy and practice.

INTERVIEWER Adele Weder

Nina-Marie Lister has made a career of embedding nature within the design of our daily lives. As founder of the studio Plandform and leader of the Ecological Design Lab at the soon-to-be-renamed Ryerson University, she has developed a nature-centric, interdisciplinary approach to landscape interventions. Her work spans between design and policy, from animal crossings built over highways, to the wilding of her own Toronto front garden, to supporting the development of the Meadoway park system on a 16-kilometre hydro corridor.

Lister has been recently honoured with the $50,000 Margolese National Design for Living Prize, administered by the School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture at the University of British Columbia. Canadian Architect contributing editor Adele Weder interviewed her at Massey College, where Lister is a Senior Fellow. The following is excerpted from their conversation.

CANADIAN ARCHITECT: Tell me more about how you work.

LISTER: The medium of my work is landscape, and it is things that are alive. When we design at a small scale and when we design responsibly—for example, with an ecological application or with the lens of ecology—we don’t risk the system. We engage in ways that are safe to fail. I work almost exclusively in partnership arrangements and in collaborations, where we co-create designs, particularly because I’m at work in a living system that is complicated and complex.

We’re living in a time of tremendous urgency between the climate emergency and global biodiversity collapse. Anything we do has to be done quickly and urgently, but with a lot of different approaches. This means trying things quickly with enough information to act now, but on a scale that’s responsible and safe to fail.

CA: In your Margolese acceptance speech, you talked a lot about projects that you didn’t get and competitions that you didn’t win. So is it fair to say that you’re more optimistic about the potential of design than the reality of current practice?

LISTER: Yes, in that we need to be brave and daring and not be afraid to break things, including boundaries. That’s why they say that second place is often the winner. Design competitions give us the space to try new ideas. Just being in competitions is an opportunity for innovation. Even if we don’t win, we still learn something from that, and we carry that forward into the next project. And we can put forth an idea that is compelling, engaging and different.

So much of design work—particularly in the private sector, or even by private sector suppliers in the public sector—when the project is completed, the designers walk away. A lot of my work is about monitoring, evaluation and resetting of goals. We consider design an engaged process of learning.

CA: Your practice involves complex biological systems. The market economy is also a very complex system, in a different way. How do you reconcile those two systems?

LISTER: I come from a very privileged position, working in a university where I’m paid to do research. But on the other hand, I’m highly motivated by the urgency of our times. And frankly, the corporate market system that created a lot of the problems we’re trying to deal with right now will not get us out. We need to find different ways of working. And while “partnership” sounds like an escape clause for both the private and public sector, it actually allows us some interesting space to innovate.

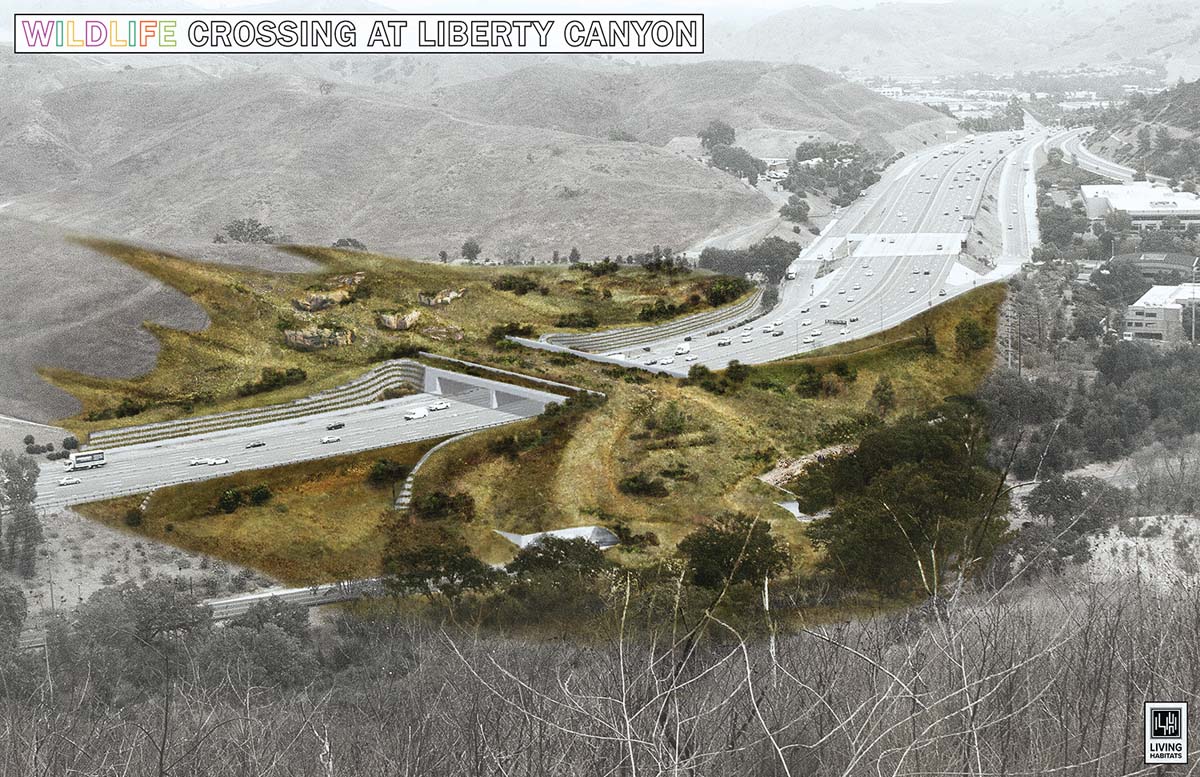

A lot of the work that I do right now is around landscape connectivity through wildlife crossing infrastructures. How do we allow humans and wildlife to get where they’re going to safely? These are not the same as the highway bridges we use for truck traffic, military vehicles, or rescue vehicles. For example, they have to support landscape overburden, and you can’t allow the edges of these bridges to settle differently for wildlife.

This means the way we think about design has to not only include the structure and the landscape for different clients—one of whom can speak and the other one who can’t—but also the system of governance and the system of maintenance, implementation and decision-making about them.

What we can do is issue procurement processes differently. We can partner with the private sector, which has more risk capital available, particularly if there is a new category of infrastructure that has very different requirements. The public sector can issue a requirement for this infrastructure on a widespread basis with the private sector. We can also establish different standards of success for infrastructure like bridges intended for wildlife.

Photo courtesy Living Habitats

CA: You’ve described animals as “clients.” How do you engage in that kind of relationship with a species that doesn’t speak?

LISTER: Oh, they do speak—just not to us. And let me clarify: nature owes us nothing, but we owe nature a pretty big debt right now, since we’re the one species that takes over the space of multi-millions of them. So it’s imperative that I work with a group of scientists and particularly people who cross the disciplines to interpret how we’re going to make sense of a world that allows for connectivity and interaction.

It’s common to talk about ecosystem services, for example, which rankles me. The living world does not provide only a service to us. It’s important for us to be able to change the way we design with, and for, the natural world, beyond simply thinking of it in utilitarian terms. That’s something that our Indigenous communities have taught and shared with us.

As a planner, I will never use the term “land use” again, even if it means relinquishing my licence. I’m a land-based practitioner. That wording is critical, because it means that I am looking at what can I do with this landscape that provides for others socially, ecologically, and economically.

CA: How do you establish performance metrics for your projects? For instance, in your wildlife-crossing: how did they measure the attempted crossings with and without the intervention?

LISTER: It is amazing how the ecological data world uses all kinds of creative observational tools. My colleagues in conservation ecology, biology, and zoology will use everything from camera trap evidence, to hair traps, to tracking evidence from footpads. Graduate students spend a lot of time measuring footprints. A purpose-designed wildlife crossing is tracked and sampled using at least three different methods. We know for sure that these projects are overwhelmingly successful. Long-term data has been gathered from different lenses, using different types of knowledge bases, for multiple species.

That analogy could be used in urban settings to look at how we understand not only green roofs, but, say, biofuels, green streets or parks. How quickly is water absorbed after a storm event in our parks, versus in hard surface areas? Our parks can be seen as so-called nature-based solutions or green infrastructure during flood events, not just for public recreation. That’s great. That’s a win. We know they’re supposed to be used for that. But what if they are also seen as cooling the urban heat island? What about as carbon sinks, for the soil sequestration of carbon?

CA: You’ve described the magic that you feel when you put your arms around a tree that’s hundreds of years old. A person can also feel that way about buildings that have been around and inhabited for centuries. The feeling is really of immortality–the sense that both the built and natural landscape can carry on and provide joy to others long after we ourselves are dead and gone.

LISTER: Yes, they connect us to each other through history. When we alter the landscape, we remediate and sometimes reaffirm the value of a landscape that has to last through time. We should treat our buildings with that long-term perspective.

CA: That ethos you’re describing applies to Massey College, the building where we are sitting right now. It’s almost 60 years old, a low-rise in the centre of Toronto, and is in no danger of demolition. But this building has caregivers—or, I guess a better word for that is stakeholders.

LISTER: Actually, I think that “caregivers” is exactly the right word. They’ve made sure that it’s updated for the times and maintained beautifully. It could have been designed and built a thousand years ago, or five years ago, and could still be here 50 years from now. Cultural heritage

is deeply and profoundly tied to natural heritage.

CA: Has the pandemic changed your approach to your work?

LISTER: Yes, it has. it’s one thing to appeal to people on behalf of other species, and another to speak to them about their new self-interest in green space. How is their health being affected by access to nature, or the lack thereof? That’s changing the way we ask research questions.

CA: Now that you’ve won the Margolese Prize, what is your ambition for the next ten years?

LISTER: Well, my goal is to be out of a job because our society will have no more need for what I do. That’s probably a longer-term plan than 10 years. In the meantime, I’ve returning to Harvard this January to co-create and teach a course called Wild Ways, which looks at landscape connectivity.

CA: And what is your hope for the future?

LISTER: I hope for more meaningful and robust connections to nature every day in our cities for everyone. I want to see those connections manifest in the material world and in public policy. Most of all, I want every person to feel that they have innate human power.