In Memoriam: Cornelia Hahn Oberlander (1921-2021)

The legacy of a trailblazer in landscape design.

When Cornelia Hahn Oberlander passed away this May, Canada lost a trailblazing landscape architect and a dear friend. Always a step ahead—and a quick step at that—Oberlander forged new territory in Canadian landscape architecture, introducing many new ideas and techniques to the field. Reflecting on her life and career, this trailblazing quality of her work really came home to me.

Born in Mülheim, Germany in 1921, Oberlander immigrated to the United States as a teenager. She was part of the second cohort of students that included women to attend Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design (GSD). After graduating with a BLA in 1947, she was determined to participate in the postwar transformations taking place in North American cities. Key to this endeavour was her collaboration with architects. This commitment to collaboration was forged at the GSD, where teachers such as Walter Gropius introduced collaborative studio problems to architecture, landscape architecture, and planning students. It was further reinforced by her time in the Philadelphia, when she worked with architect Louis Kahn and landscape architect Dan Kiley, as well as with architect Oscar Stonorov.

Cornelia and her architect-husband Peter Oberlander arrived in Vancouver in the 1950s. Both were proponents of cross-disciplinary collaboration, and soon Oberlander was working on single family homes with architects such as Frederic Lasserre, Harry Lee, and Thompson Berwick Pratt and Partners. In an article for The Canadian Architect in 1956, she advised architects and landscape architects to “explore the possibilities of a site, so that the house and the area around it be planned as one unit.” She stressed the importance of fitting the house to the land: a site-focused design approach that would become emblematic of architecture and landscape architecture in British Columbia.

Oberlander was also landscape architect for the city’s first experiments in social housing, McLean Park and Skeena Terrace, with the CMHC, Harold Semmens and Underwood McKinley Cameron. Oberlander’s 1962 planting design included trees with grand canopies, such as copper beech and gingko. These stately trees are still standing today, and contribute greatly to the atmosphere of their projects, providing dappled light and counterbalancing the scale of the towers, helping them fit into their surrounding neighbourhoods.

Oberlander’s collaboration with Arthur Erickson on Robson Square was her most celebrated. The project also commenced a professional relationship that lasted 36 years and involved numerous projects in Canada and the United States. Erickson once remarked, “most landscape architects I’d use before were too […] sentimental […] not tough enough. Not intellectually up to the challenge. But I remember Cornelia felt the potential.”

At Erickson’s office, she met young architects Bing Thom, Nick Milkovich, and Eva Matsuzaki, who would fashion their own successful practices and work with her on future projects. It was also at Robson Square that Oberlander began to pioneer her skills in successfully bringing plant life into complex urban projects, an aptitude that she would continue to hone working with Erickson at The Canadian Chancery in Washington DC (1988) and the Laxton/Evergreen Building (1981, 2009), with Moshe Safdie at Library Square (1995, 2018) and The National Gallery (1988), and with KPMB Architects at the Canadian Embassy in Berlin (2005).

Sometimes her landscapes became the key symbol of a project. The New York Times Building Courtyard (2007)—a project she collaborated on with Renzo Piano, Fox & Fowle, and H.M. White Site Architects—is a good example. Visible from the main lobby and the auditorium, her lush green courtyard with its tall birch trees has appeared in numerous photographs of the project and features prominently in The New York Times’s promotional material. This notoriety came with its price, however. Apparently, birds like the courtyard as much as humans. One disgruntled tenant called Oberlander in Vancouver and asked her to get rid of the birds, because they were making too much noise.

Oberlander also blazed trails in the creation of children’s outdoor play environments. Never a subscriber to off-the-shelf playground equipment, she continually explored how natural materials and spaces created with earthen mounds and plants could function as conduits for play and spontaneous exploration. Decades ahead of her time, Oberlander also embraced risk-taking in play—witness her signature “wobble walls,” created with logs stacked on-end in a line. This play feature was adopted in other playgrounds throughout Canada—although they were usually much shorter than Oberlander’s wobble walls, which sometimes reached well over a metre in height.

Her first landscape for children was the Bigler Street playground in Philadelphia, which was so innovative, it was featured in Life magazine in September 1954. But her most famous children’s environment was for the Children’s Creative Centre at Expo 67. Here, Oberlander used the basic elements of landscape—terrain, water, plants, and structures—as well as loose parts, such as logs, that could be freely manipulated by children. I still encounter adults today who fondly remember playing in Oberlander’s Creative Centre at Expo 67.

As Oberlander’s career progressed, she continued to create sustainable landscapes that were sensitive to ecological processes. She also forged new ground by incorporating plants valued by Indigenous peoples well before other landscape architects were doing so. Oberlander was decades ahead of the times in her work at UBC’s Museum of Anthropology, where she designed an ethnobotanical landscape featuring plants used by Indigenous people for medical and nutritional purposes. Ferns—whose spores had been used to make powders for healing wounds—and mahonia shrubs—whose berries were consumed raw or used in jams and jellies—were planted in the undergrowth of the preserved forest. Oberlander’s entryway mounds were planted with her custom seed mix of long grasses and sand dune flowers. This could be considered one of the first instances of the now-popular “rewilding”–and it was 1976!

Oberlander’s deep commitment to ecology and Indigenous cultures ultimately led her to the North—another trailblazing direction in her career. About ten years ago, landscape architects began looking to the North, where the impacts of climate change are exacerbated. In 2011, for example, the Nunavut Association of Landscape Architects hosted the Canada-wide CSLA congress. Of course, Oberlander had been there decades earlier. Beginning in 1991, she consulted with Pin/Matthews Architects and Matsuzaki Wright Architects on the Northwest Territories Legislative Assembly in Yellowknife. This project prompted her to invent a novel planting approach that embraced her dictum “plant what you see.” In the 1990s, no nursery in Yellowknife was willing to grow plants from seed for her landscape. So, she collected seeds, clippings, and tissue cultures of kinnikinnick, rose hips, saxifrages, vaccinium and other plants from the Yellowknife site. This material was transported back to Vancouver for cultivation in greenhouses. When planting in Yellowknife began, she returned with the vegetation—genetic progenitors of the plants that had been growing on the site.

These were planted using a technique she called “invisible mending.” Borrowed from sewing, the goal of invisible mending was to attract as little attention as possible to the stitch itself. Applied to the landscape, plants were not installed in defined planting areas, but instead interspersed in disturbed areas and bare patches—an approach that made the planting process invisible. Oberlander liked to joke about an American garden historian who visited the Yellowknife site. The historian kept complaining to the tour guides that she couldn’t find Cornelia’s planting beds.

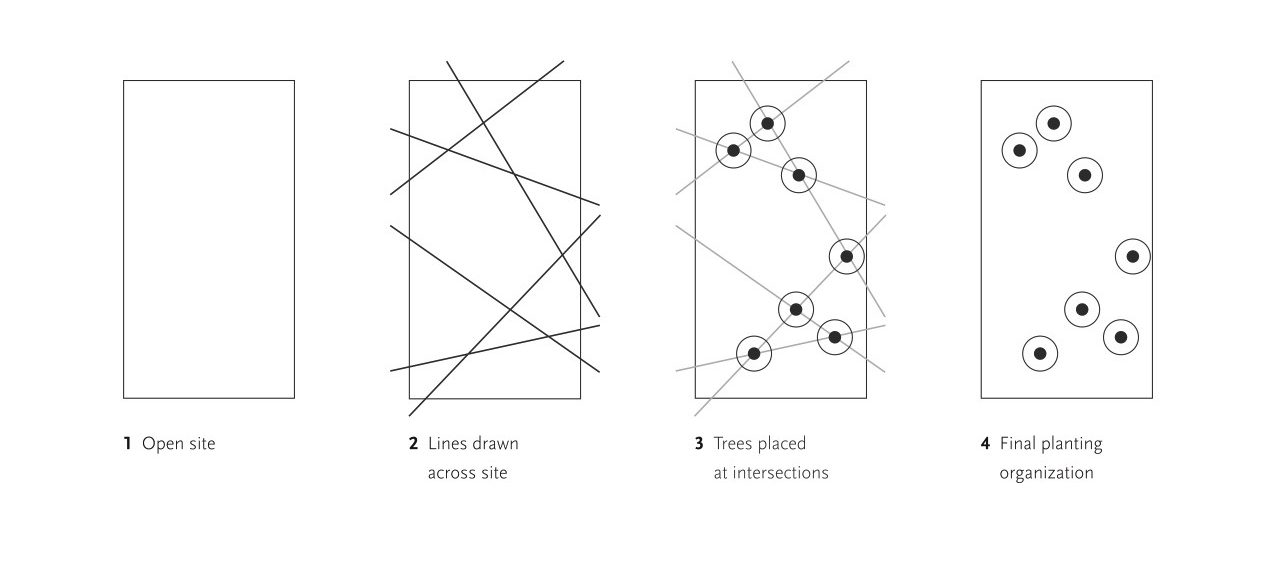

Oberlander returned to the North to work on the landscape of the East Three School in Inuvik with architect Gino Pin. In Inuvik, Oberlander combined her commitment to collaboration, her knowledge of children’s play environments, and her “plant what you see” approach. She also invented a unique layout scheme for trees that addressed the extreme conditions of the North. A major challenge in the Arctic is the formation of snowdrifts, exacerbated by the Coriolis Force—the deflection of wind movement caused by the rotation of the earth, which is greatest at the poles. With climate change, lower, stronger blowing snow combined with the Coriolis Force made snowdrift calculations increasingly complex. To protect the school and the children, Oberlander devised a tree layout method that created a landscape-integrated shelterbelt, helping to refract blowing snow and avoiding accumulation up against the school and its entranceways.

Interestingly, her tree layout method was inspired by a point-and-line exercise which Oberlander had been exposed to as a student at the GSD in 1946, when the school was experimenting with Bauhaus Vorkurs methods. The exercise was meant to create a balanced randomness. Oberlander drew random lines across the borders of the East Three School site plan, and placed dots where lines intersected each other, with each dot locating the position of a tree. The original intent of this Bauhaus-inspired method was to enhance the movement of the eye and the visual imagination. For Oberlander, it also provided a means of refracting snowdrifts.

Oberlander’s trailblazing approach to landscape architecture has yielded outstanding results. Canada’s designed landscapes would not have been the same without her. It has been an honour to learn from her amazing work—and to become one of her many friends who admired her quick sense of humour, unstoppable determination, and contagious optimism for the future. She is sorely missed.

Susan Herrington is a professor in the landscape architecture program at the University of British Columbia’s School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture (SALA). She received the John Brinckerhoff Jackson Book Prize for her book Cornelia Hahn Oberlander: Making the Modern Landscape (University of Virginia Press, 2014).