From Matter to Place: A Camp for the Transmission of Inuit Local Knowledge

Pierre-Olivier Demeule

WINNER OF A 2019 CANADIAN ARCHITECT STUDENT AWARD OF EXCELLENCE

Pierre-Olivier Demeule, Université Laval

Advisor: Myriam Blais

For the Inuit of Nunavik—the northern region of Quebec—the traditional activities of hunting and fishing contribute to a sense of place. Today, they are also linked to healing, recreation, crafts and socialization. From this point of view, tundra camps are the mainstays of local identity and Inuit well-being.

Despite its proximity to existing settlements, the land remains accessible to few, due to the high costs of travel and construction. Resilient buildings are needed, whose layout and materials can adapt to changing Northern conditions. What can be learned from Inuit camps, which both symbolize and provide access to the tundra? How can the know-how behind the existing modest buildings inform new, resilient spaces that maintain a beneficial relationship with the land?

This project proposes a new tundra camp located two kilometres from the village of Salluit (62ºN), along a fjord accessible by canoe or ATV. The proposal’s key spaces facilitate the expression and transmission of local knowledge. It creates a restorative and responsive architectural environment, inviting spirit and soul to harmonize with the tundra.

The project explores the concept of sustainable vernacular architecture. It seeks to combine local know-how, local materials, and Northern construction processes. By doing so, it supports a model of healthy co-dependence between ecosystems, culture and the local economy.

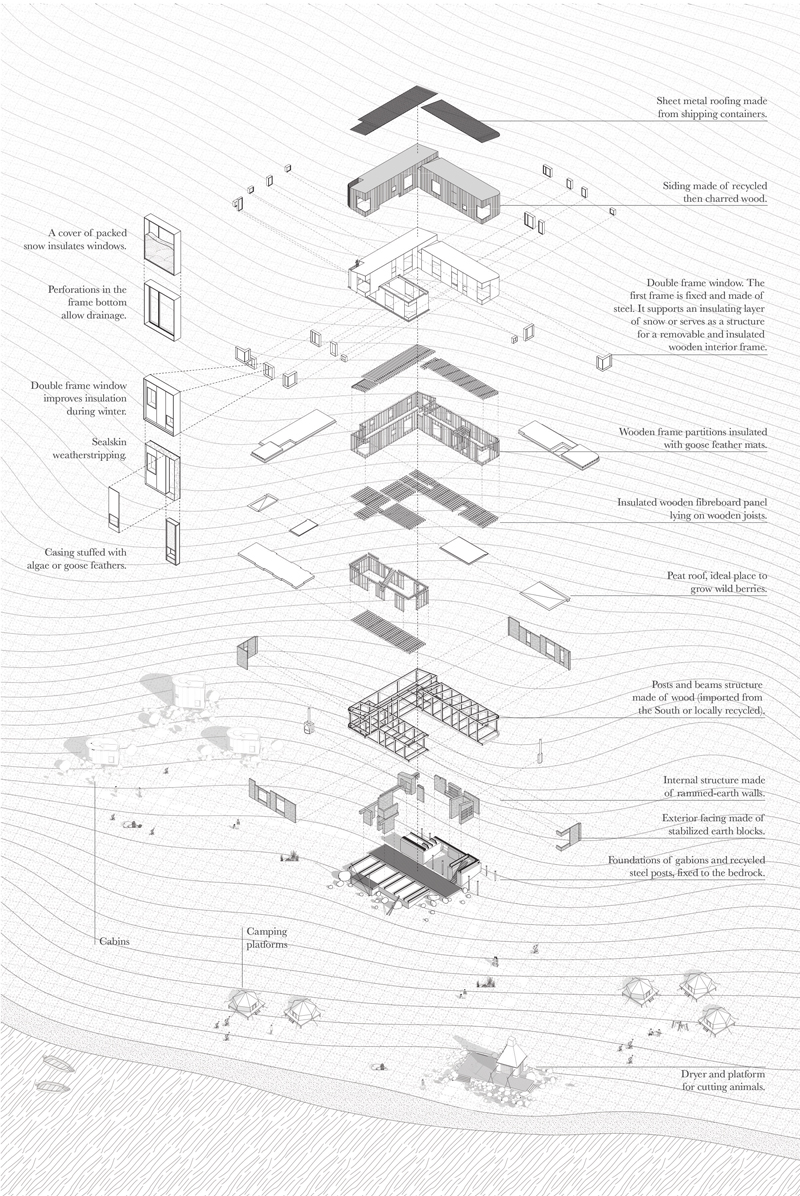

Components of the camp include an expandable community hall, cabins, camping platforms, and a hut for drying animal skins and meat. Each element has a limited ecological footprint. The structures use passive heating and cooling strategies. They use natural materials such as goose feathers for insulation, sealskin for weather stripping, and peat for roofing. The buildings adapt to each season with strategies such as adaptive fenestration, and a flexible use of space according to the time of year.

The project aims to further local capacity and autonomy with construction methods that can be replicated, adapted or transformed by the Inuit. The project also promotes “soul-healing.” Its spaces strengthen community ties and enable activities that allow for the sharing of Inuit values.

The new camp can be transformed and evolve over time according to local needs. At each design phase, the project aligns itself with the principles of Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit, meaning “living technology” or “what the Inuit have always known.” The design and construction of this place of healing hopes to demonstrate the ingenious know-how of the North—a Qaujimajatuqangit that can reconnect the Inuit to their land in ways that are harmonious, innovative and adaptive.

Jury Comments

Rami Bebawi :: Perhaps the word “resilient” is what seems to bring to life the value of this project. I greatly appreciate this forward-thinking attitude that attempts to contemporize past values.

Joe Lobko :: A traditional Inuit camp reinterpreted and reimagined, applying contemporary building science and traditional cultural understanding in the effort to create a resilient and adaptable model. A wonderfully presented project with a thoughtful and convincing thesis.

Cindy Wilson :: This beautiful project is both a record of the past and a window to the future. The use of natural materials to support more contemporary building methods is intriguing, and these materials are more accessible in the context of a northern climate.