Things are Looking Up: Union Station Food Court, Toronto, Ontario

The new food court of Toronto’s Union Station features multi-functional, space-age ceiling pods, whose design was led by Toronto studio PARTISANS. Architect Alex Josephson tells Canadian Architect how his upstart firm landed a role in the renovation of Canada’s busiest transit hub.

PROJECT Union Station Food Court, Toronto, Ontario

ARCHITECTS PARTISANS in collaboration with DIALOG and GH+A

Cultivating a future client

Seven years ago, I bought a ticket to a Charlie Burger event—one of those secret dinners where they fly in a renowned chef. I was seated across from a tall, confident stranger who was wearing a bespoke western rodeo-inspired plaid suit. After realizing our common love for architecture and food, he passed over his card and explained that he worked for a real-estate holding and development company named Osmington. I had never heard of Osmington. Plus, that jacket?!

A few months later, the stranger—Brad Keast—reached out to see if the studio that I co-founded with Pooya Baktash, PARTISANS, was interested in working on ideas competitions with him. He was clear that there was no guarantee for any work, but we would have an opportunity to try and impress some heavy hitters in the development community.

Brad’s email arrived at a time when PARTISANS was practicing out of a 500-square-foot loft; we had just moved from the inside of a storage facility’s loading dock. For two years, we worked on competitions together. The best we did was second place.

Bidding on a long shot

We eventually learned that Brad had an important project on the go. Around 2006, Osmington had won the bid for a 75-year head lease over most of the retail spaces in Union Station, and was inviting designers to submit proposals for an interior fit-out. As part of a larger renovation, Union was being revalued as a significant place in the country. Osmington saw the potential for Union to become one of the world’s most engaging civic experiences.

When PARTISANS inquired, we were told that the likelihood for us to be considered was slim to none—but that if we wanted to submit a bid, we were welcome to do so. We put a package together that included a partnership with the world-renowned Massimilliano and Doriana Fuksas. I had worked for them in Italy. The day of the submission, I delivered it in-person at the Osmington offices in a custom-made box. They smiled, but explained that the project required a partner located closer than Italy, with more grey hair than mine. They needed insurance. But they ultimately decided that they wanted to keep us involved. Fuksas was out, but we had gotten our toe in the door.

Finding a role

In many ways, Union Station is a bit of a miracle, given the challenges that its redevelopment has faced. The base building architect, NORR, along with many collaborators, pulled a rabbit out of a hat in excavating a whole new level under the existing train tracks, which needed to remain in continuous operation. Much credit is due to them.

PARTISANS was part of the interior fit-out team for the commercial spaces as well as helping to create the vision. We worked in collaboration with NORR, GH+A, DIALOG, Beauleigh, Hammershlag Joffe, RWDI, LightEmotion, and others. In 2013, our technology-driven studio contributed a stand-alone 3D BIM model that eventually became a design and construction tool for all participating architects, engineers and consultants. It not only demonstrated the scale and scope of the project, but also enabled an efficient sharing of information, facilitated the phasing of Union’s tenant fit-outs, and allowed for maximum flexibility while delivering the project.

At first, our contribution of the BIM model was treated with skepticism by the base building and contracting teams. There were, after all, almost a decade of standard CAD drawings that constituted the project. Yet, we felt it was important to understand the exact dimensions and components of the spaces to be able to fit them out.

To create the model, PARTISANS hired ten Revit-fluent Ryerson University graduates. The team compiled the existing drawings and used laser-scanning to develop the model, which offered a clear, three-dimensional picture of all the issues the project was facing. Pipe by pipe, duct by duct, wall by wall, the context emerged. We could finally start designing.

Wrestling with MEP

What we discovered through four rounds of design—during which we weren’t sure if we would keep our jobs—was that MEP systems drove everything. The complexity of these items tended to lowest-common-denominator solutions, like drop ceilings, which leave plenty of space for trades to do whatever they want above, but at the cost of beauty and complex future maintenance. Rem Koolhaas, at his Venice Biennale curatorial stint, commented on this problem, noting that present-day systems take up more space in buildings than even humans do!

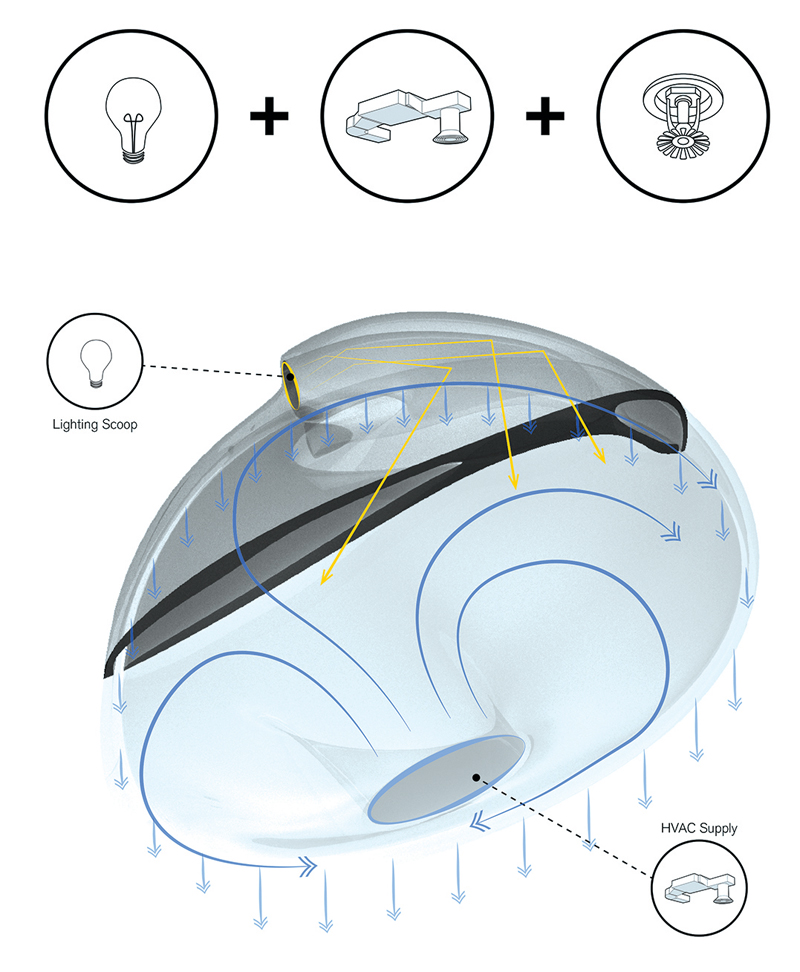

On the lower level of Union, having a dropped ceiling would mean settling for a food court with an eight-foot-high ceiling. We concluded that a fully custom idea was needed to maintain the open ceilings, while accommodating everything from lights to fire sprinklers in the areas around the bulky HVAC runs.

Do you remember that scene in Apollo 13 where the engineers convene in a room and work together to “build a filter”? That is exactly what happened at Union Station. On our final round of design, we were able to gather every engineer in one place and ask: “Can we come up with a way to house sprinklers and water pipes, HVAC ducts and diffusers, a light fixture, and speakers in one single component?” We looked around the world for precedents. The group was particularly inspired by the original open disk ceiling at the Marcel Breuer-designed Whitney Museum in New York (now the Met Breuer). For Union, the result was the Pressurized Ocular Diffuser—or POD for short.

Inside the PODs

The sculptural PODs turn infrastructure into a set of aesthetically intriguing objects. 210 cloud-like structures playfully hover over the seating area, fitting in the spaces around HVAC runs and equipment to preserve the open ceiling. There are only two standard designs, but the amorphous form produces a strong sense of visual variety.

The PODs are the culmination of extensive research into the architectural potential of combining multiple building systems into singular sculptural objects. Off-the-shelf products are economical, low-risk solutions to increasingly complex HVAC requirements—and their intractable practicality has become a significant (albeit de facto) part of architecture. The PODs disrupt this status quo and reinvent the possibilities of the ceiling by blurring the distinction between architecture and systems design.

Each POD integrates an HVAC pressure vessel, light diffuser and sprinkler head into a single rigorously performative architectural object. It consists of two shells that nest together to form a plenum. The outer shell forms the HVAC pressure vessel and duct inlet, conceals lighting equipment, and provides hardware attachment points for installation. The inner shell acts as the luminaire. The gap at the edges of the two shells serves as the air diffuser; the sprinkler head is accommodated in a pocket at the apex.

The geometry was developed collaboratively with consultants including aerodynamic, lighting and mechanical engineers. Numerous digital simulations, including computation fluid dynamics analysis and illuminance studies, were conducted for both individual and aggregated PODs to inform the geometry and demonstrate feasibility. Performance was later verified with extensive testing of full-scale mock-ups.

Combining systems into a single object had the downstream benefits of streamlined coordination, accelerated installation and simplified layout changes. The food court portion of the retail concourse featuring the PODs opened to the public in late 2018.

We learned, in working on Union, that design opportunities emerge from unlikely places—a meeting with a stranger in a plaid suit, a determination to overcome the obstacle of a ceiling duct. We learned that design requires a village and a lot of people willing to have an open mind in situations where that feels almost impossible. When enough time is allotted for failure and iterations, then, beauty emerges. Innovation takes time, patience and a lot of teamwork.

Alex Josephson is co-founder of Toronto firm PARTISANS.

CLIENT Osmington Inc. | MECHANICAL The Mitchell Partnership | ELECTRICAL Hammerschlag & Joffe | CONTRACTOR PCL Construction | BUILDING PERFORMANCE RWDI | LIGHTING LightEmotion | CODE LRI Engineering | RETAIL Beauleigh Retail Consulting | AREA 2,322 m2 | BUDGET Withheld | COMPLETION November 2018