Ten Indigenous Designers

We take a deep dive into the work of ten Indigenous architects and designers whose names may be relatively unknown at present, but who are working in thoughtful ways deserving of attention.

Canada has a small but growing number of Indigenous architects and Indigenous designers working in allied fields such as interior design, planning and landscape. Here, we take a deeper dive into the work of ten of these practitioners whose names may be relatively unknown at present, but who are working in thoughtful ways deserving of attention.

These practitioners represent a range of ways that Indigenous thinking can impact design. Land-based practices are at the forefront for many of them: Jason Surkan begins his projects by living on the land, while Kelly Edzerza-Bapty is making use of forest-fire-killed wood as the structural timbers for buildings. The four elements are integral to Jason Hurd’s design for the Dakota Dunes Resort Hotel (pictured on this page), while Naomi Ratte aims to convey the connection between people and place in her recent work on a team masterplanning a national park in Iqaluit.

Community engagement is also key to Indigenous methodologies, although it is different for each project. David Thomas has been part of a large team with several Indigenous designers and many Indigenous stakeholders working on a revolutionary masterplan for a neighbourhood-scale development for an urban reserve in Winnipeg. Rachelle Lemieux and Nicole Luke have completed much of the design for a recent project through the pandemic, shifting from in-person to online engagement of communities.

The practitioners featured also bring a variety of disciplinary perspectives to their work. Destiny Seymour made her name designing textiles inspired by artifacts from her culture; she’s now partnered with Mamie Griffith in taking on architectural and interior design projects. Tiffany Creyke brings design insight to the client side of projects as the Director for Indigenous Design & Projects for Vancouver Coastal Health.

While our profiles put the spotlight on Indigenous designers, for each of them, the work has a larger purpose: it’s about empowering Indigenous communities. How can design uplift the people who encounter it, and facilitate deeper connections to the land they live on? This is work that goes beyond the hero image in a magazine, but that aims to strengthen communities and cultures, setting solid foundations for the future.

Kelly Edzerza-Bapty

Nzen’man’ Child and Family Development Centre

Inklucksheen Reserve, BC

TEXT Emma Steen

Obsidian Architecture founder Kelly Edzerza-Bapty is rethinking typical ways of making architecture. Her Indigenous-owned and -operated firm works predominantly with First Nations across the Yukon and British Columbia through slow, community-led approaches. Coming out of an education in industrial design and architecture, where she did not see herself reflected, Edzerza-Bapty says that having a female-led Indigenous practice was a priority. “I’ve tried partnering with bigger firms, and realized that a lot of the time, you are still tokenized. They want you there when they need to check the boxes and put an Indigenous face forward, but you are never offered equity beyond consultation, and are not in the meat of the construction documents: you are merely ‘Indigenizing’ their designs.”

Edzerza-Bapty’s projects often include hiring Indigenous community members, and developing regionally specific designs that speak to the Nation they serve. Her process slows down production to make time to sit with—and build trust with—community. “We’re not quick in, quick out,” says Bapty. “[In client consultations,] I ask for different groups of elders, often in gender split, and local Indigenous language speakers, as well as the members that are running the programming in communities. We try to do at least a full-day workshop with youth in the community each time we come in: we’ll run model-building workshops, and design-thinking sessions with iPads, markers, laptops with 3D building files. These youthful contributions to the design process, programming, and final project are valuable. In this participatory approach, we’re thinking about [buildings] in terms of being in place for several generations, of having that longevity and durability. We are investing in ‘generational architecture’ and ‘generational building.’”

BC’s accelerating history of wildfires has led Edzerza-Bapty and her team to reconsider how designs can work in a world where natural disasters and environmental changes are becoming more frequent. One strategy has been to harvest wood charred by forest fires for construction—once the burnt portions are removed, it’s essentially kiln-dried timber. Collecting and clearing out the wood also reduces the risk of future forest fires and accelerates the forest’s regeneration. “When fires come through and burn hot and quick, they leave really beautiful timber behind,” says Bapty. “If the fire comes through a second year, it’s fuel. So what if we plan to go out and do a selective timber harvest that can also work as a restorative approach to land management?” It’s the kind of holistic outlook that Indigenous Nations have always held, she adds.

Edzerza-Bapty plans to use fire-killed timber for the interior structure of the Nzen’man’ Child and Family Development Centre for the Nlaka’pamux community in the southern interior of BC. Her work on that project started in 2017, when she was commissioned to design a new facility to combine all of the organization’s services into one building. When the town of Lytton and the surrounding area were hit by wildfires in 2021, destroying the spaces that they were renting in the interim, the pressure to fund a new building increased.

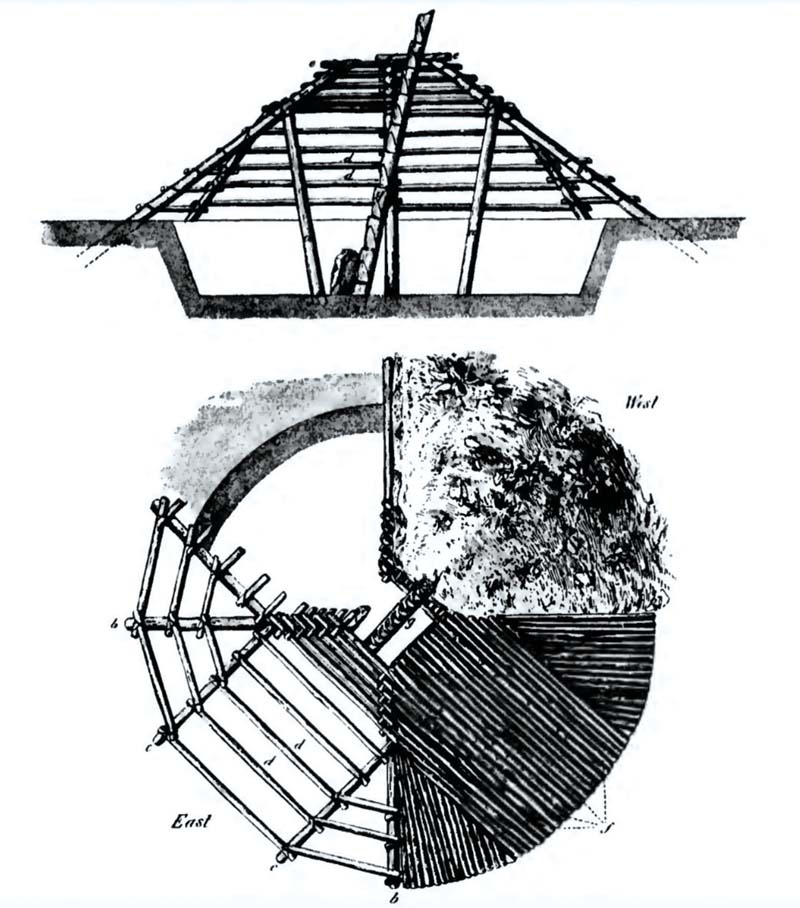

The new centre, which will be located in Inklucksheen Reserve along the Fraser River, is a land-bermed form that backs into the hillside like a shieshkin (pit house) with red, rammed earth walls—a local material and naturally fire-proof construction. “In the different canyons going north, there are red-hued rocks—when the sun hits them, they are very vibrant,” says Edzerza-Bapty. “We have the pit house as a model of vernacular architecture from that region, which was our inspiration for the building form and structure. The building faces the Stein Valley, an area with lots of pictographs—these hold many stories, including a Nlaka’pamux birthing story.”

Edzerza-Bapty says that the centre has “an amazing board of women working there,” and has taken on services including childcare, early learning, youth and elder programming, disability services, food and family programs, and in-home care. “They bridge a lot of the shortcomings created in the community from the reserve systems and from a 80-year history with a residential school. These women are putting reconciliation in action, within their communities, and under their own systems. It’s a community approach to reconciliation.” Still, the centre has struggled for funds to ensure the building can be completed. “It’s hard to find funding for organizations like this that are doing all the right work,” says Edzerza-Bapty. “There’s a gap at the government level for putting equity in Indigenous organizations and Indigenous-run projects.”

Nonetheless, Edzerza-Bapty points out that even adversity can bring new possibilities. “A fire is a rebirth. After a forest fire comes through, the first year it feels devastating. But the next year, it’s a field of fireweed, there’s a regrowth that happens. That’s how Indigenous communities are: they are resilient. If we have the chance to do it differently or better, we will.”

Jason Hurd

Dakota Dunes Resort Hotel

Whitecap, SK

TEXT Pamela Young

Dakota Dunes Resort Hotel is a new, 155-room getaway destination with a lot of history behind it. Traditional Dakota territory encompasses parts of present-day Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario and the upper Midwestern United States. Following the buffalo, Dakota led by Chief Whitecap (Wapaha Ska) made seasonal rounds through the Prairies until the 1870s, when the Canadian government forced them onto reserve lands. Chief Whitecap settled his followers in Moose Woods, slightly south of present-day Saskatoon, where they became cattle ranchers. Today, Whitecap Dakota First Nation is a progressive, 600-person community that operates a golf course, a casino, and, since 2020, the resort attached to the casino.

For Jason Hurd, managing partner of aodbt architecture + interior design’s office in Prince Albert, Saskatchewan, it was important for the Dakota Dunes hotel to convey Whitecap Dakota First Nation history and culture in a way that was meaningful and modern. Hurd, who is Métis, grew up in Prince Albert, where his family has lived since the 1870s. He completed his Master of Architecture at the University of Waterloo in 2007 and worked in cities including London, Melbourne, New York, and San Francisco, before returning to Prince Albert, where he joined aodbt in 2009 and became a partner in 2012. Established in 1980, the firm has a staff of 60 split between its Saskatoon and Prince Albert offices, and has many First Nation clients. “It’s important to be curious, ask a lot of questions, and come with an open heart,” Hurd says of the consultation process with Indigenous clients. “You have to set any preconceived ideas about the project at the door and see where the process takes you.”

Working closely with the client team and a local Indigenous graphic designer, aodbt, in association with LEMAYMICHAUD Architecture Design, developed a design concept for Dakota Dunes based on the four elements and strongly influenced by the Dakota connection to the land. The lobby, with its freestanding fireplaces and charcoal tones and textures, represents Fire. Lined with a river-rock trough and with a suspended, handcrafted canoe as its focal point, the Water-themed main-floor corridor connecting the lobby to the restaurant, lounge and conference centre highlights the Saskatchewan River’s importance to the Dakota as a transportation and trade route. The Land-themed restaurant and bar celebrate Whitecap Dakota ties to buffalo and cattle. The guest rooms, with floor-to-ceiling views of the dunes, represent Air. Angled wood panels on the façade and the slanting mullions of the guest-room windows allude to the dynamism of tipi forms and grass bending in the wind.

All parts of the hotel, and especially the rooftop pool, provide expansive views of the region’s distinctive, windswept dunes. To Hurd, two of the most successful design aspects are the transparency of the ground floor and its connectivity to the landscape, with an outdoor amphitheatre and celebration space including a firepit. These exterior gathering areas are partially enclosed by the wind-blocking volume of the hotel tower. “The community hosted ceremonies there for Truth and Reconciliation Day, with a tipi encampment, dancers and food—everything happening in that outdoor space, with people sitting on the embankment,” he says. “It was very much how we hoped it would function, and it made me very happy.”

Destiny Seymour and Mamie Griffith

aabijijiwan New Media Lab

Winnipeg, MB

TEXT Pamela Young

In Anishinaabemowin, “aabijijiwan” means “it flows continuously,” like rippling water. Interactions between Indigenous traditions and new technologies ripple outward from the University of Winnipeg’s aabijijiwan New Media Lab, which opened in 2021. Here, labs containing animation, VR and green screen equipment, along with 3D printers and a laser cutter, border an open space where a beading workshop or sage-wrapping session might be in progress. Interior designer Destiny Seymour led the conversion of 372 square metres of standard-issue academic space into aabijijiwan. “Renovations are challenging,” she says. “You have an existing box, and you’re dealing with ideologies that don’t necessarily fit in that box.”

But Seymour, who is of First Nations descent on both sides and identifies as Anishinaabe, was well equipped to transform this box into an appropriate vessel for its contents. At the University of Manitoba, she completed an undergraduate double major in psychology and anthropology and a masters in interior design. Over more than a decade with Winnipeg-based Prairie Architects, she designed interiors for many Indigenous schools and community buildings.

Her inability to find textiles reflecting the Indigenous cultures of her own region took her career in an unexpected direction. Patterns on museum artifacts such as a 400-year-old elk antler scraper tool inspired Seymour first to sketch, and then to take a silk-screening course. In 2016 she left Prairie Architects to focus on her Indigo Arrows textile collection. Her table linens, pillows and quilts rapidly attracted a following—Seymour and Winnipeg-based garment manufacturer FREED recently introduced a line of home textiles for Urban Barn, a chain with stores throughout western and central Canada. In 2018 Seymour and architectural designer Mamie Griffith (Dene) founded Woven Collaborative; the studio’s mission is to “respectfully reflect local Indigenous cultures & identity within architectural forms, interior spaces, furniture, and textiles.”

Seymour and Griffith selected an earthy palette of purple, ochre and sage to lend warmth to the aabijijiwan New Media Lab. To director Dr. Julie Nagam, co-director Dr. Jaime Cidro of the affiliated Kishaadigeh Collaborative Research Centre and other members of the (mostly female) client team, it was important for the space to feel welcoming to women and children. Seymour designed a curved screen in reclaimed elm wood that, during a workshop, affords a breastfeeding mother some privacy while still enabling her to follow the presentation.

The lab’s drum stools are a type of custom furniture that Seymour has incorporated into many other projects. However, she says that upholstering them in Pendleton blanket wool—as she has done until recently—always felt like a compromise. Although the blanket patterns are inspired by North American Indigenous motifs, they are not genuine expressions of specific Indigenous cultures. In partnership with Winnipeg-based Anishnaabe beading artist Cassandra Cochrane, Seymour and Griffith recently generated an alternative for use on future drum stools. Like the aabijijiwan New Media Lab, it is a fusion of tradition and technology: Woven Collaborative has vectorized a floral pattern by Cochrane, and is now offering it in three colourways, printed on durable, easily disinfected commercial-grade vinyl.

Rachelle Lemieux and Nicole Luke

Michif Manor

Winnipeg, MA

TEXT Omeasoo Wahpasiw

Launched in 2019, the Government of Canada’s Indigenous Homes Innovation Initiative aimed to support Indigenous-led housing ideas. One of the 24 projects selected for support was Michif Manor, a place for Métis families from outside of Winnipeg to stay while they or a family member seeks medical treatment in the city.

The design for Michif Manor is being led by Métis architect Rachelle Lemieux and Inuk designer Nicole Luke, who work with Verne Reimer Architecture. For both, intergenerational ideas of community caring and sharing were key to the design. A central atrium creates a visual connection to the sky and natural elements outside, welcoming sunlight during Winnipeg’s long winter and forming the warm heart of the building. “We try to think of what a grandmother’s house feels like, because this is a home away from home,” says Lemieux.

Lemieux’s family has an intergenerational history in the building arts. “When I was growing up, I would walk by this preserved house in St. Norbert (McDougall House, 3514 Pembina Highway), and I didn’t know it, but my grandmother told me later, ‘your Great Great Grandfather built that house’,” says Lemieux. For her part, Luke says that she has always been passionate about culture and design. “I grew up realizing there is limited representation of Indigenous people in professional fields, and this was reflected on the architecture.” She aims to “learn culturally appropriate ways of designing, to be the best learner possible, and to apply [the appropriate cultural nuances] to each project.”

Ensuring both individual and group interaction, the Manor includes a communal kitchen, lounge, games area, and quiet space. Ten double-occupancy rooms accommodate one to four people, while two family rooms sleep up to six. The variety of spaces ensure that guests will both have privacy, and be able to heal alongside others in community. Beyond addressing the physical needs of guests, the building aims to provide emotional, mental, and spiritual comfort. “The building itself will be one of love, safety, and warmth, where individuals may be proud of their heritage, and share with others that are going through the same experience,” says Lemieux.

Outreach and continued engagement are fundamental to Lemieux and Luke’s design process, and during the pandemic they have continued to consult broadly using social media, Teams, Zoom, and surveys. They hope this will create a solid foundation for their work, and ensure it remains a positive asset to Manitoba’s Métis Nation. Says Lemieux, “I would like for future generations—my nieces and nephews and Indigenous youth—to feel proud of their heritage and see themselves reflected in the cities and buildings where they live, work and play.”

Jason Surkan

Round Prairie Elder’s Lodge

Saskatoon, SK

TEXT Omeasoo Wahpasiw

As a 13-year-old growing up in the Treaty 6 territory near Kistapinânihk (Prince Albert, Saskatchewan), Jason Surkan saw the documentary Radical Attitudes: The Architecture of Douglas Cardinal. It ignited dreams to become an architect—work that brought him into contact with Cardinal himself, while undertaking his Bachelor of Architectural Studies at Carleton University. Surkan continues to explore: “What is a contemporary Métis architecture?”

Surkan is a member of Fish Lake Local #108, and his Métis ancestry traces back to Hudson’s Bay Company families, including men from the Orkney Islands, women from Turtle Island, James Bay Cree families, the Red River Resistance, and a great grandfather who operated a sawmill in the Montreal Lake area. His current work with David T. Fortin Architect allows him to live in his homeland, a prairie-to-boreal forest ecological zone that has provided so much for so many. His own approach is grounded by Elders such as Maria Campbell and inspired by the efforts and ingenuity of ancestors who used their environment for materials.

For the Round Prairie Elder’s Lodge, a project for the Central Urban Métis Federation Inc. (CUMFI) in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Surkan began the project by living on the land. The building, now coming to completion, is literally grounded in Surkan’s experience of the place, as well as in his community- and equity-focused approach. “Architecture should respect and give back to the land on which it sits,” says Surkan.

The Lodge needed to be affordable, but this constraint did not limit its beauty and realization of a specific Métis intent. A bright façade visually references the white lime-mortar plaster of historical Métis homes in the Batoche area of Saskatchewan, contrasting with a dark plinth that references a traditional Métis practice of spring grass burning. Patterns inspired by Métis floral beadwork are cut into exterior solar window shades, which welcome in warm winter sun but shade interiors from harsh summer rays. The front entry of the building—as well as the wood cladding in several interior spaces—features a chevron pattern that is reminiscent of the Métis sash.

Surkan also drew on local materials and traditional Métis construction techniques. For the entrance canopy, round, raw pine log ends from the Boreal forest are slotted into a horizontal beam like the logs in a Red River Frame. Continuing to use local wood products, Surkan designed a fireplace enclosure that nods to Hudson Bay frame houses with their heavy corner posts, and planks slotted in and fastened with dowels. “A lot of the Métis would have flagstone in the entranceway, so we also used flagstone around the fireplace,” says Surkan.

The themes of historical Métis homes continue through to the outdoor landscape, which features a central hearth to encourage community gathering. In this way, Surkan and his team have flipped the colonial experiences of Métis visibility. In the past, says Surkan, Métis homes often took on a European appearance from the outside, while maintaining egalitarian and open spaces inside that were reminiscent of tipi life. Outside the Round Prairie Elder’s Lodge, Métis Elders will now take their place in the sun, enjoying their final journeys as proud Métis supported by one another, and by a place designed with love for the Nation.

Tiffany Creyke

Integrated Health Centre (with VIA Architecture)

Vancouver, BC

TEXT Emma Steen

as the Director of Indigenous Design & Projects for Vancouver Coastal Health (VCH).

Working at the crosswords of design, community and infrastructure, Tiffany Creyke navigates public art, Indigenous health and bureaucracy as the Director of Indigenous Design & Projects for Vancouver Coastal Health (VCH). Coming from a planning and sustainable development background, Creyke says her mission is to “create safer spaces for the local community” within VCH’s facilities. She adds, “whosoever’s land the structure is sitting on, people should feel represented, seen and safe.”

Creyke leads the development and dissemination of resources for Indigenous health and wellness, working across multiple Nations and protocols to create meaningful spaces for Indigenous communities to gather and feel cared for in the City of Vancouver and its surroundings. But space and land are not neutral in what we currently know as Canada, and funding adequate opportunities to represent host Nations—as well as urban Indigenous peoples—is a constant balancing act.

health centre in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, with VIA Architecture. Rendering courtesy VIA Architecture.

“[The need for] reparations goes beyond what you can see, because that is the only way you are going to have sustainable movement,” says Creyke. “Reparations must also include having structural policy pieces in place, so every single person who is involved in the design development of a building is following the same protocol and process.”

Creyke sees the development of health infrastructure through the lens of her work as a curator, community organizer and planner. One of her many projects has involved leading the client side of the design of a new Integrated Health Centre in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, where she has been working closely with Squamish, Musqueam and Tsleil-Waututh matriarchs.

“Embedding traditional knowledge into contemporary design through the direction of matriarchs—that, to me, is a respectful way of going about this work here,” says Creyke. She shares that the corner structure, designed by VIA Architecture, includes “a sea kelp façade running up the building, with carved house posts and large carved doors that provide a sense of welcome and safety with Indigenous design.” She adds that the building will radiate light “out onto the pavement when it’s dark, creating amenity for the homeless population in that area—we are not only thinking about the people in the space, but those living around the space.”

Community empowerment is integral to Creyke’s goals of reclaiming spaces to serve Indigenous communities in a meaningful and responsible way. “Spatial justice is having yourself represented in the space that you’re in that goes beyond just putting up a piece of art,” she says. “I am trying to get us to the point where we are designing around programming that is more intentional.”

David Thomas

Naawi-Oodena

Winnipeg, MB

TEXT Pamela Young

and Design for Treaty One Development Corporation.

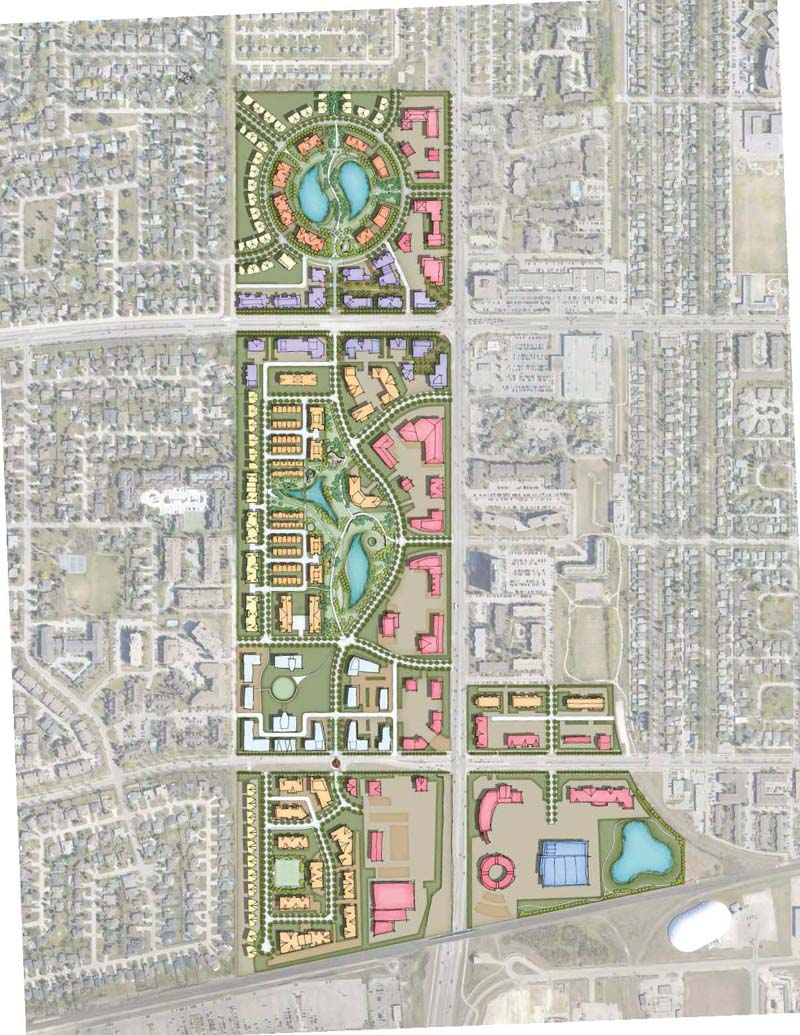

Like a plant sprouting from rocky soil, an inspiring land-sharing agreement in Winnipeg has emerged from a pile of broken promises and legal battles. In 1871, with the signing of Treaty 1 at Lower Fort Garry, Manitoba, the Crown made land allotment commitments to seven First Nations that were never fulfilled. When the 65-hectare Kapyong Barracks site in southwest Winnipeg was vacated in 2004, it was initially turned over to the Canada Lands Company, an arms-length Crown corporation, to arrange for its sale. In 2008 the leaders of Treaty One Nation, the umbrella organization formed by Treaty 1’s First Nation signatories, launched a lawsuit. The upshot of their successful suit is that 68 percent of the former barracks property, now renamed Naawi-Oodena (“centre of the heart and community,” in Anishinaabemowin) will become an urban reserve, with the Canada Lands Company developing the remainder of the site. Infrastructure construction will begin in June 2022, and when full build-out is achieved in approximately 15 years, Naawi-Oodena will accommodate up to three thousand new residences and 111,000 square metres of commercial space.

David Thomas brings lived experience, a designer’s skill set, and a readiness to be “a sponge for ideas” to his role as Manager of Planning and Design for Treaty One Development Corporation. Raised in Winnipeg and a member of Peguis First Nation, he was making $11.35 an hour in a bank job and supporting a young family when he enrolled in the drafting program at Red River College. He graduated and went on to complete a Master of Architecture at the University of Manitoba. With his daughter, Cheyenne Thomas, a U of M Bachelor of Environmental Studies graduate, he is now guiding final design stages of the Indigenous Peoples Garden in Canada’s Diversity Gardens at Winnipeg’s Assiniboine Park. He is also active in an international Indigenous designer’s network and was a contributor to UNCEDED, Canada’s official exhibit at the 2018 Venice Architecture Biennale. “As a First Nation person I feel that we had levels of communication and storytelling that we’ve lost,” he says. “As a designer, I’m committed to figuring out how we can tell stories, how we can express who we are.”

Thomas and many others in Winnipeg’s Indigenous design community—including Destiny Seymour, who is also profiled in this issue—were instrumental in producing the Former Kapyong Barracks Master Plan, released in March 2021. Like any contemporary master plan encompassing multiple blocks within a developed urban context, it addresses issues of zoning, circulation and community space. But unlike virtually any other, it proposes integrating wild rice production with stormwater management, incorporating public realm features highlighting the cultural significance of the cardinal directions, and designing rest areas where people can observe weather patterns, water quality, animal behaviour and plant growth.

Overall, the plan envisages an urban Indigenous space that expresses Indigenous values and highlights the character and history of the seven Treaty One communities. It lays the foundation for an urban centre that celebrates the rich culture and language of the Anishinaabe people, bringing together Indigenous governance, community, and economy.

Thomas notes that Winnipeg already has two small urban reserves. He has an office at Peguis First Nation’s 1.5-hectare urban reserve on Portage Avenue, which he says has “a sense of community that I’ve never really experienced before.” On Naawi-Oodena, he’s involved in everything from ensuring that buildings are configured to support the types of meetings that will take place in them, to providing technical support to the financial team. “It’s such an extensive project,” he says. “I can’t wait to see what it’s going to become.”

Naomi Ratte

Iqaluit Parks Master Plan (with Chris Grosset, NVision, and Chelsea Synychych, HTFC Planning + Design)

Iqaluit, NU

TEXT Pamela Young

Naomi Ratte, who describes herself as “a mixed-race woman of Pakistani and Anishinaabe heritage,” is interested in identity and connections between people and place. At the University of Manitoba, where she is pursuing her Master of Landscape Architecture, she co-founded the Indigenous Design and Planning Students’ Association (IDPSA) and co-edited the 2021 IDPSA publication Voices of the Land: Indigenous Design and Planning from the Prairies. In it, she and 15 other Indigenous U of M students answer the question: “Why are you studying design and how do you bring your cultural identity into your work?”

As an artist, Ratte won Canadian Heritage’s Art in the Capital Competition in 2018, transforming Ottawa’s York Steps into a salmon-themed artwork titled Jump!. At the start of the pandemic, she began learning beadwork—one of a lineage of important crafts that Indigenous people have refined with each generation. To her, one of the most inspirational aspects of beadwork is the community around it; Ratte participates in a beading circle with several other emerging Indigenous designers from Winnipeg.

Ratte’s cultural identity also comes out in her work since 2017 as a technical researcher with Ottawa-based Indigenous consultancy NVision Insight Group. Her work with NVision includes a landmark master plan for two Iqaluit parks that received Community Joint Planning and Management Committee approval last December. The Iqaluit Kuunga Nunalingnut and Qaummaarviit Inuit Nunagiqattaqsimajatuqanginni Master Plan establishes a 20-year stewardship and development framework for the Nunavut capital’s most visited park, 4,310-hectare Iqaluit Kuunga (formerly Sylvia Grinnell Territorial Park) and the 15-hectare Frobisher Bay island Qaummaarviit, a sacred heritage site occupied for more than 750 years by Inuit, Thule, and Dorset cultures.

Landscape architect Chris Grosset, NVision’s senior consultant on the master plan and a former Nunavut Parks Division employee with decades of experience in the region, explains that Iqaluit Kuunga is both “a gateway park for people making their first visit to Nunavut and the backyard park where the community recreates.” Key master plan aims are to ensure that rapidly intensifying visitor day-use will not impede traditional Inuit uses of the land, such as harvesting, and to protect landscape and cultural features in intensively visited areas with boardwalks and other infrastructural interventions. The linchpin strategy is to have community members share the responsibility for setting parks-related policies with government.

Ratte participated in several capacities throughout the master plan development: she was part of fieldwork and committee meetings, and assisted in the development of site plans, renderings, mapping work, and final design document layout. Through this visual representative work, she strives to use her role and perspective to convey the connection between people and place, helping to communicate “why this place is so special.” She says that connections to land have been continually disrupted by external forces, and brings an understanding to the work that “our connection to land can be sustained, reconnected, or discovered through landscape architecture.” She adds, “for me, it is about showing how the land is a reflection of us, our heritage and our future.”

Recent fuel contamination crises at Iqaluit’s water treatment plant have underscored the importance of the master plan’s recommendations for improved access to a freshwater collection site within the park, used by many area residents. Equally significant is the park’s recent renaming. What the Government of the Northwest Territories established as Sylvia Grinnell Territorial Park in 1974 (25 years before Nunavut’s creation), was named for the daughter of 19th-century U.S. explorer Charles Francis Hall’s patron—someone who never set foot in the region. The traditional Inuktitut name, meaning “place of many fishes” is now the official one. “For that name to be officially recognized by the Territory is a step in reconciliation,” says Ratte. “It creates an invitation to tell a story about the landscape, just as the name describes.”