Settler-Colonial Modern

Architectural historian Magdalena Milosz considers postwar residential schools and the illusion of progress.

Writing about modernism in colonial contexts, architectural historian Gwendolyn Wright proposes that “the physical environment became a strategy for enforcing common values while maintaining difference within a conjoint modern world.” In Canada, little else exemplifies this statement so strongly as the century-long experiment known as residential schools.

Recent confirmations of unmarked graves at the former Kamloops Residential School in unceded Secwépemc territory and several other former residential school sites ignited a national conversation about this history and its ongoing consequences. For Indigenous communities, it has been a time to grieve, as it should be for us all. For settlers, it has also been a wake-up call to take a more critical look at Canadian history, particularly the recent past and present of settler-Indigenous relations.

As a settler-colonial nation, Canada’s access to territory has always been predicated on the removal of its prior occupants. This took place through sequestering Indigenous peoples on reserves or congregating them in permanent settlements, as well as separating children from their families and communities through residential schools—a system the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada called “cultural genocide” in 2015. The primary purpose of these institutions was to re-educate children for assimilation into settler society. Many suffered hunger, abuse, and neglect at the hands of keepers. Although much of the system was phased out in the late 1960s and early 1970s, the last institution did not close until 1997.

Non-Indigenous Canadians are most likely familiar with residential schools through news stories featuring photographs of old-fashioned classrooms with children sitting in orderly rows, or of imposing brick buildings constructed a hundred years ago. Yet there is a more recent, lesser-known visual vocabulary of this system: architectural modernism, harbinger of progress and, in Wright’s words, of “brutal destruction” as well.

Modern residential schools reflected the government’s desired progressive image vis-à-vis Indigenous peoples after World War II, when it embraced a policy of “integration.” The atrocities of the war brought more widespread attention to human rights issues and the disparate treatment of Indigenous peoples in Canada. Indigenous soldiers had made significant contributions during the war, and had been able to vote in federal elections while in service—a right extended to all status Indians only in 1960. The Indian Act was amended in 1951 to remove some of its more restrictive provisions, such as those prohibiting cultural practices, political organizing, and retaining lawyers. The government also promoted home ownership, citizenship, and participation in the settler economy.

Despite sending more children to provincial public schools and fewer to segregated federal day and residential schools, the federal Department of Indian Affairs continued to build new residential schools and additions in the postwar period. Like public schools of the same era, these institutions promised to educate children for a prosperous future as productive citizens, on an equal footing with other Canadians. In contrast to the overbearing, historicist structures of the 1920s and 30s, residential schools designed and built after the war suggested that the government was leaving behind paternalism and oppression for equality and democracy.

But the seemingly progressive visual and spatial codes of residential schools in this era served to mask continuing power imbalances and oppression. The modernization of residential schools did not change the fact that Indigenous children were still separated from their communities and taught a primarily Eurocentric curriculum. The image of the modern residential school disrupts notions of postwar architectural optimism and complicates the sense of these institutions as part of a distant past. In their adoption of modernism, these structures also sought to become invisible among quite disparate settler architectures.

A project for a new building at the Kainai Nation (Blood Tribe) in Treaty 7, Alberta, for example, would have been indistinguishable from any non-Indigenous school in a postwar suburb. Designed by the Department of Public Works around 1950, it was a low-rise block with a rhythmic grid of windows and spandrel panels on its front elevation and an off-centre, recessed entrance. The design was likely intended as an additional classroom building at one of the reserve’s two residential schools, but it was never built. At both the Anglican St. Paul’s and Roman Catholic St. Mary’s schools, the government ultimately opted for more utilitarian solutions, setting up a link trailer building and a disused military structure as classrooms.

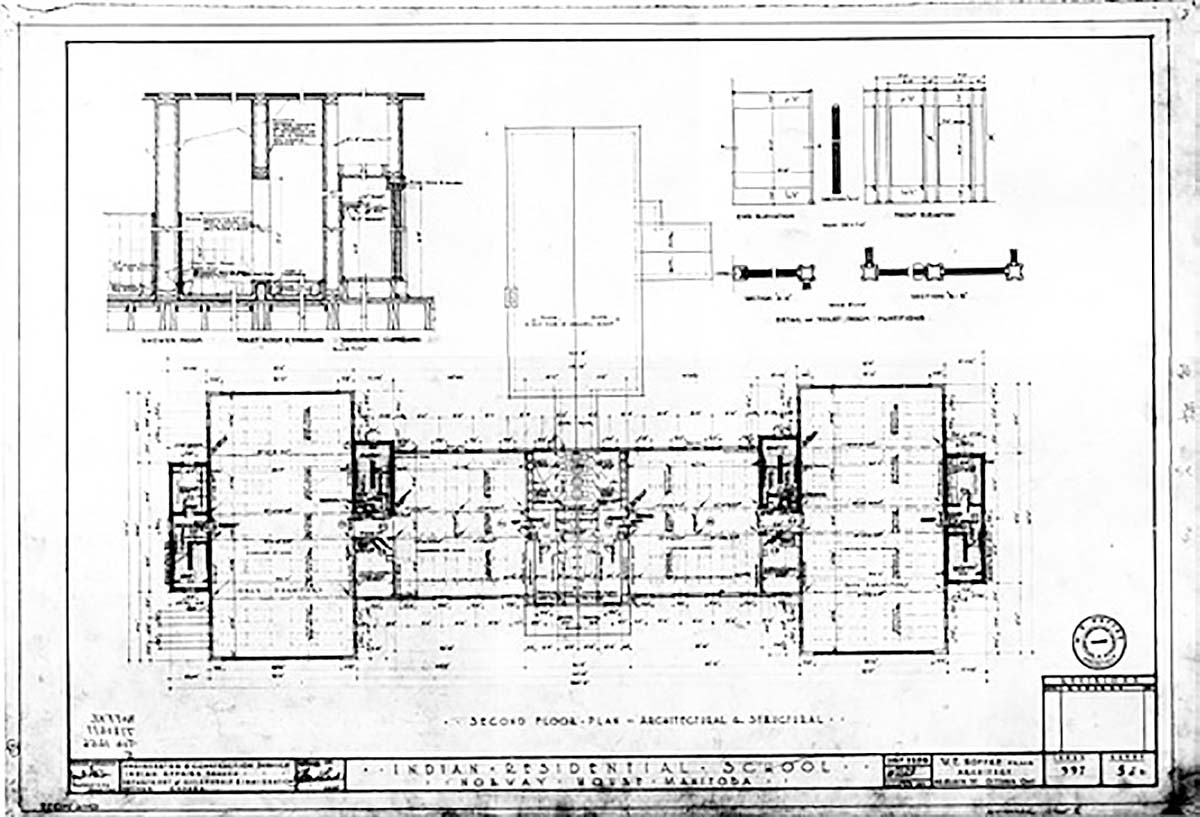

Another school, built in 1954 in Treaty 5, Manitoba, shows how a modern exterior could be used almost like clothing to disguise an old plan. The Norway House Residential School had a central block flanked by symmetrical, two-storey wings, with classrooms on the ground floor and dormitories above, as well as a rear wing with a chapel, assembly room, and dining hall. The plan facilitated segregation of children by gender and age, often separating siblings who were in the same institution. It resembled the two dozen residential schools built by Indian Affairs in the 1920s and 30s—including in Kamloops—and made reference to an even earlier residential school, the Mohawk Institute in Six Nations territory (Brantford, Ontario), built in 1905.

The former MacKay Residential School in Treaty 2 (Dauphin, Manitoba) is one of only sixteen residential schools that are still fully or partially standing in Canada. It was designed by the Engineering and Construction Service of the Indian Affairs Branch in the Department of Citizenship and Immigration (a successor to the Department of Indian Affairs), and built in 1957. The main building was accompanied by outbuildings including a principal’s residence—built as a single-family house—as well as a married teachers’ residence and quarters for single staff in the form of small apartment buildings.

The substantial school structure has a horizontal profile, with strips of windows set in buff-coloured brick, and a two-storey portico at the entrance. With its rows of classrooms, gymnasium, and cafeteria, the building resembled a conventional secondary school: with the exception of a conspicuous, four-storey dormitory block at the building’s west end, where the children lived. The site is currently used by a Christian charity, Parkland Crossing, to provide affordable housing and other services. Survivors periodically gather there to honour their time at the institution, and in recent years, the site has seen more commemoration with a monument and plaque. An interior space has also been set aside for the use of survivors.

In the postwar period, the federal government was also making efforts to teach English to adults in remote Indigenous communities. In the late 1950s, Indian Affairs and the National Film Board put together a filmstrip called “We Learn English” that presented everyday scenes in a simple, painted graphic style with short captions. The section on “The Community” featured images of a picturesque village, with houses, a church, and other peaked-roofed buildings arranged on a rolling hill. The one exception was the school, which featured a flat roof and ribbon window—the result of Indian Affairs’ request for the artist to render “a neat, newly-painted, modern school.” While this was a day school, not a residential school—the children who attended went home at night, but were still taught to see their own cultures as inferior—the image suggests the power of modern architecture to represent the government’s supposedly forward-looking attitude towards Indigenous education at this time. The filmstrip conspicuously omitted any discussion of residential schools.

Although residential schools may seem like marginal architectures, known only to the children who lived in them and the anonymous bureaucracy that kept them there, in the postwar period, they were very much products of mainstream architectural culture. In 1961, the Vancouver firm Gardiner Thornton Gathé & Associates, whose archives are held at the Canadian Centre for Architecture, built a new complex for St. Mary’s Residential School in the unceded territories of the Stó:lō and Coast Salish (Mission, British Columbia). The three-storey dormitory could hold nearly 250 children and was built alongside a one-storey school, refectory, chapel, and gymnasium. A large cross towered over the buildings atop a tall tripod base.

The St. Mary’s project was published in the September 1965 issue of the Journal of the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada (JRAIC) as one of the inaugural winners of the Department of Public Works Design Awards for Architecture. The awards recognized “distinguished accomplishment in federal government buildings” and “were judged on the basis of the solution of the problem presented to the architect.” The buildings’ compositions of reinforced concrete, loadbearing masonry, and glued laminated timber clearly impressed the jury, which consisted of architects Raymond Affleck, Victor Prus, and Charles Elliott Trudeau (brother of the future prime minister).

Today, the former St. Mary’s residential school is situated within Pekw’Xe:yles, a small reserve shared by twenty-one First Nations. Survivors give tours through what remains of the school, sharing their horrific experiences of being separated from their families for months or years at a time, and of physical and sexual abuse, in the hopes of raising awareness about this history. This is what Wright refers to as “the underside of modernism”: a celebrated image of progress overturned to reveal the difficult histories of which it is a part.

Four years later, another residential school project was recognized with the same design award: a gymnasium and chapel addition for the Assiniboia Residential School in Treaty 1 territory (Winnipeg), by the federal Public Works design team for the Western Region. Assiniboia was a rare urban residential school, opened in 1958 and located in a repurposed school building from 1918. The new gym and chapel consisted of two austere blocks topped by clerestory windows, built of concrete masonry and connected by a vestibule and breezeway. These buildings, as well as the original repurposed school, still exist, but have been adapted to other uses. Survivors of Assiniboia recently published their experiences in a book called Did You See Us? Reunion, Remembrance, and Reclamation at an Urban Indian Residential School, which assembles a complex portrait of the residential school experience.

In the late 1960s, Assiniboia—along with many other residential schools—was converted into a “hostel” or “residence” where children lived while they attended public schools in nearby settler communities. While many of these “hostels” were simply repurposed residential schools, some were purpose-built. The Christie Residential School, in the unceded territory of the Nuu-chah-nulth (Vancouver Island), was condemned in the late 1960s and replaced by a new “Indian student hostel” in 1971. An article published in the August 1969 issue of The Indian News, a government publication distributed to First Nations across the country, noted that “except for sports, there will be no teaching at the residence.” Instead, the children, who would come from “100 miles of the Pacific coastline,” would attend the elementary school in the town of Tofino.

A perspective of the Christie project, designed by Indian Affairs architect J.W. Francis, shows the dormitories, administration building, and cafeteria as a series of buildings with asymmetrical roofs, all nestled against the sweeping backdrop of a mountain range. Francis was also the designer of the Indians of Canada Pavilion at Expo 67, which had become a complex site of negotiation as a committee of Indigenous representatives struggled to reclaim their nations’ representation on the world stage.

The hostel project was described in explicitly progressive terms and made some acknowledgment of the children’s cultural diversity. “To make the environment more formal and friendly,” noted the Indian News article, “an attempt will be made to capture an authentic Indian quality through the use of Haida carvings and totems, a Nootka welcoming figure and several murals done by well known west coast Indian artists.” The use of art had also been a strategy to “Indigenize” the Expo project two years earlier, bringing up questions of visual and architectural sovereignty in the midst of widespread Indigenous political activism.

Recently, Chris Clarke McQueen, my colleague at McGill University, shared with me his own experience with the obscurity of modern residential schools. Clarke McQueen is from the Treaty 8 Akaitcho Territory Łutsël K’é Dene First Nation, and is Chief Architect with the Department of Health and Social Services of the Government of Northwest Territories. He recently learned that the elementary school he attended as a child was originally built in 1958 as the Fort Smith Federal Day School. This institution was operated by the government as part of a larger complex that included a church-operated hostel, together recognized by the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement as the Breynat Hall residential school. Designed by Rensaa & Minsos Architects for the Department of Public Works, the Fort Smith Federal School bore the typical modernist idiom of postwar elementary schools.

“I think that’s why I never knew,” Clarke McQueen says of the history of the building. “Was it a disguise?” I was struck by that, because it conveyed so succinctly the invisibility of settler colonialism in the built environment. Modernism, in this case, seems to conceal its own underside, covering up its tracks so that architecture associated with the systematic cultural genocide of Indigenous peoples continues to be used—sometimes without much awareness of its history. Following the revelations at Kamloops, there have been renewed calls to demolish Breynat Hall, the Fort Smith Federal School’s hostel, which is now a residence at Aurora College. The building is associated with trauma for many survivors who still live in the community, and the college has found that the history of the residence deters potential students.

Knowledge of these histories and their location in the space we now know as Canada is uneven, and certainly their manifestations in the built environment are not yet widely known. Modern residential schools highlight how recent these histories are, and how easily they blend in with other institutional architectures of their time. They bear witness to the complexity of modernism, and its potential for envisioning a future that comfortably accommodated oppression while shielding it from scrutiny. Looking more carefully at these architectures can reveal less positive, but ultimately more truthful, histories of the built environment.

Magdalena Milosz is a PhD candidate in the Peter Guo-hua Fu School of Architecture at McGill University. Her research focuses on architecture as a site of encounter between Indigenous Peoples and the settler-colonial state from the 1920s to 1970s.

1 Gwendolyn Wright, “Building Global Modernisms,” Grey Room 07 (Spring 2002): 125.