Pundit of the Public

A new book of essays celebrating the work of George Baird doubles as an account of the climate of architectural ideas in Europe and North America from the 1960s to the present.

When academic stallions are sent out to pasture, the last thing some are saddled with is a festschrift. These are collections of laudatory essays from colleagues and former students. While appreciated by their subjects, these books are often of limited impact and import, and—like most end-of-career gifts—wind up on display on office shelves.

What University of Toronto Daniels School professor Roberto Damiani has created is not a token festschrift in honour of his colleague George Baird, but something much more interesting, original and enduring. The Architect and the Public: On George Baird’s Contribution to Architecture is nothing less than a comprehensive account of the climate of architectural ideas at all stages of Baird’s career, from when he obtained his B.Arch. from the University of Toronto in 1962 right up to the present. Contributing essays and interviews to the book are international beacons like Kenneth Frampton, Joan Ockman, Michael Hays, Mark Baraness and Peter Eisenman, plus such leading lights of Canadian architectural culture as Bruce Kuwabara, Louis Martin, John van Nostrand, Hans Ibelings and Adrian Blackwell. Because of the range of these contributors and the depth of their ideas, this book is essential to understanding the life and work of the most important architectural thinker Canada has ever produced.

Since most of his career was devoted to writing and teaching architecture, and less to the design of buildings, it is a sign of just how inclusive Canada’s architectural culture has become that George Baird was awarded the RAIC’s Gold Medal in 2010. In similar fashion, the RIBA awarded its 2014 Royal Gold Medal to scholar-critic Joseph Rykwert, although it is impossible to imagine the AIA ever awarding its own Gold Medal to Peter Eisenman or Michael Sorkin. Many of Damiani’s contributors note that Rykwert is actually one of Baird’s key mentors, despite never having formally been his teacher or editor.

London Versus New York

As a Toronto architecture undergraduate, Baird traveled to Finland on a 1959 exchange, sparking an interest in Alvar Aalto that led to a book on his work eleven years later. Baird met Rykwert after he moved to London in 1964 to pursue doctoral studies under Robert Maxwell at the Bartlett School, his intended subject being “The use of semiological concepts in architectural theory.” With not just semiology but the first waves of other French and Frankfurt School cultural theories in the air, Beatles-era London was a much richer milieu than Toronto or Helsinki, so Baird’s interests in art, literature, film, cuisine and music expanded while there. Frequent sparring partner Reyner Banham was down the hall at the Bartlett, and nearly all the other critics and theorists who would dominate English-language architectural writing for decades were publishing or teaching in London at that time: Charles Jencks, Colin Rowe, Alan Colquhoun, Kenneth Frampton and others. With the decline of the British economy and support for academe, within a decade, every one of them was teaching in the United States.

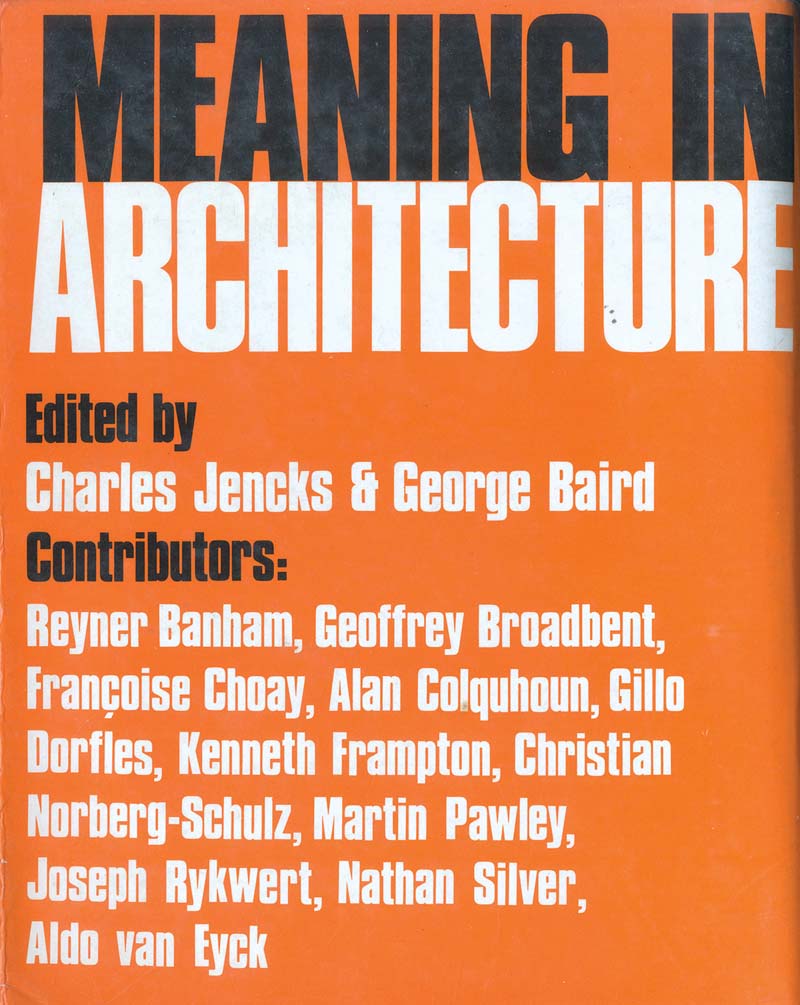

Baird sat in on some of Rykwert’s Essex seminars (where Daniel Libeskind and Alberto Pérez-Gómez were students somewhat later); Rykwert forged links for the Canadian to start teaching and publishing in London. As one of the first architectural theorists to dabble in semiotic theory, a major legacy for Baird was his 1967 Roland Barthes-inspired essay “‘La Dimension Amoureuse’ in Architecture,” which was revised to become an anchor essay in the ambitious anthology he and Charles Jencks edited in 1969, entitled Meaning in Architecture.

Louis Martin provides a lucid and highly readable exposition of the provenance and ideas of each of the essays in Meaning in Architecture, which included all the critics mentioned above, plus Aldo van Eyck and Christian Norberg-Schultz. (Damiani’s introduction to The Architect and the Public, plus the essays by Martin, Joseph Bedford, Joan Ockman and Adrian Blackwell, are all superb examples of critical scholarship, providing a foundation for the book’s other chapters, and doing much to clarify the complex theory debates of the 1960s and 70s.) In a simple but breakthrough move for presenting architectural commentary, Jencks and Baird’s Meaning in Architecture reserved space on its pages for contributors to publish comments along the margins of their peers’ essays—shells within shells of ideas, at a time when new theories churned and recombined. Damiani employs a version of this editorial device in his own book, cross-referencing the convergence and divergence of ideas from different writers by tagging links, using little arrows followed by suggestions: “see Blackwell, Frampton, Kuwabara,” for example.

Meaning in Architecture had an immediate impact on both sides of the Atlantic. Peter Eisenman recounts in his sometimes evasive 2017 interview with Damiani that “It was an important book, one of the most important at that time […] a knockout.” Prior to the London debates and their expansion to New York’s Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies (founded by Peter Eisenman in 1967 after he completed his own studies at Cambridge), architectural theory had been dominated by the shallow appropriation of ideas imported from the physical or social sciences—what Denise Scott Brown skewers as “Physics Envy.” But semiotics would not come to dominate architectural thought, and Baird abandoned most of its analytic techniques almost immediately; Jencks followed suit a decade or so later.

A key turning point was Peter Eisenman’s tough review of the book in Architectural Forum in 1970, where he proposed that Baird and Jencks confused semiotics with semantics. Louis Martin’s summary of Meaning in Architecture from today’s perspective is that it consists of “Theoretical fragments from structural anthropology, semiology, semiotics, and English literary criticism […] an unfocused chorus of voices, which postponed the promised theoretical synthesis.” With this, Martin implies that “theoretical synthesis” is a desired or inevitable goal, but Baird’s subsequent career shows his diminished interest in the abstract construction of thought systems. He decided not to seek a “theoretical synthesis,” but instead immersed himself in teaching, practice, urban advocacy, and the focused criticism of buildings. This may have been the best decision Baird ever made.

When I was an undergrad studying film history and production in the early 70s, Meaning in Architecture was my own introduction to architectural theory—semiotics had become the intellectual fad of the moment for film theorists, and I wondered how it all applied to design. Later, when I was an architecture student working for Edmonton firms, some Toronto colleagues introduced me to Baird. He went on to become an editorial and academic mentor to me. As a student, I wrote essays on John Lyle, as well as on the Edmonton City Hall Competition (to which Baird had submitted a conceptually seductive design), for two of the only three issues ever produced of the Toronto journal Trace, which Baird co-founded.

Toronto, GSD, Toronto

Despite his early success teaching and writing in London, Baird returned to Toronto at the end of the 1960s. He had been offered an appointment at the University of Toronto, and also judged that practice would be more of a possibility in Canada than in an England in decline. Given the ever-shifting landscape of architectural theory then, Damiani proposes that there were also intellectual reasons why Baird returned: “In Toronto, he could take advantage of a certain distance from both the European and American urban crises, and nurture an optimistic vision of the future of public space.” Baird’s innate optimism is noted by nearly half of the contributors to the book.

Coupled with this was a new interest in phenomenology sparked by Rykwert, and an increasing immersion in the ideas of political philosopher Hannah Arendt—in particular, her 1958 book The Human Condition. Baird was one of the first writers to apply her ideas to architecture, and especially urbanism. Within several years of arriving back in Toronto, Baird appeared on stage with Arendt at a symposium about her philosophy at York University. Although he commenced writing at that time about how Arendt’s political philosophy could inform conceptions of public space and community, the book consolidating his interpretations—The Space of Appearance—would not appear for nearly two decades.

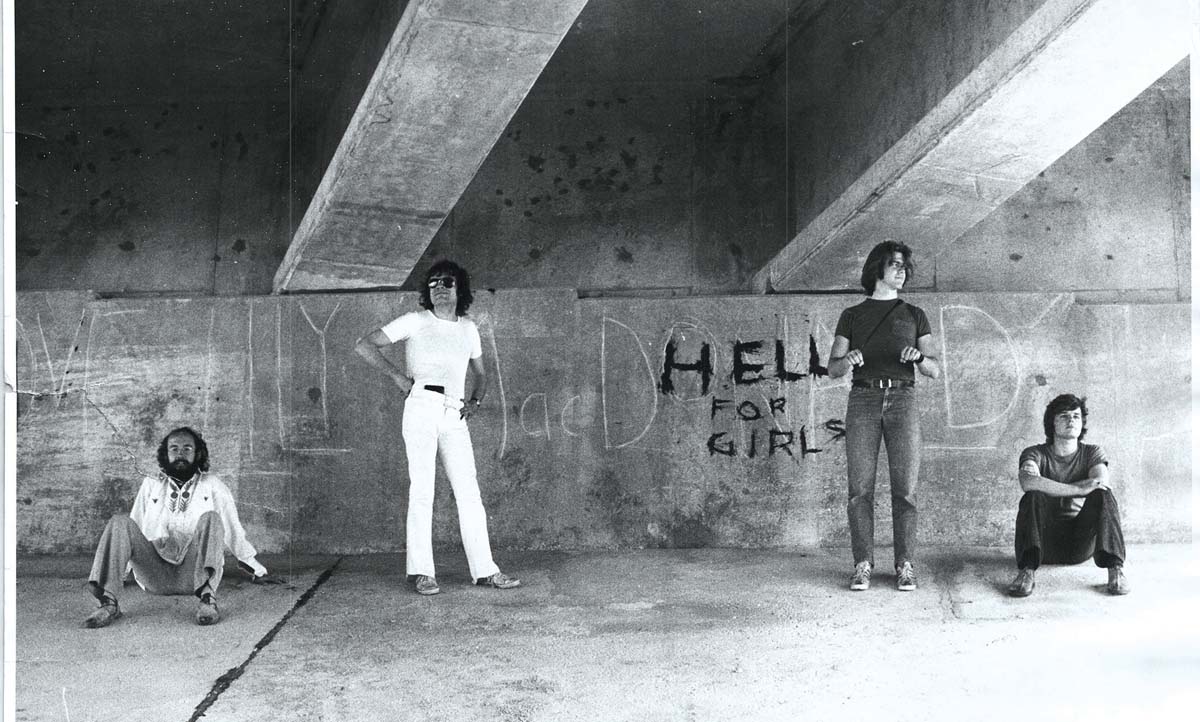

Settling in at 230 College Street, Baird at first became a close associate of architecture school director Peter Pragnell, also newly arrived from Britain. By the mid-1970s, the two had split, raising tensions all around, but the ensuing debates and clashes over curriculum and ideas ultimately enriched the education of their students. In 1972, Baird engaged four of those students to renovate the premises on Britain Street that he shared with publisher James Lorimer. Thus is born one of the mythic hinge points of Canadian architectural culture—Bruce Kuwabara, John van Nostrand, Barry Sampson and Joost Bakker, all at the business ends of paint rollers, renovating the building.

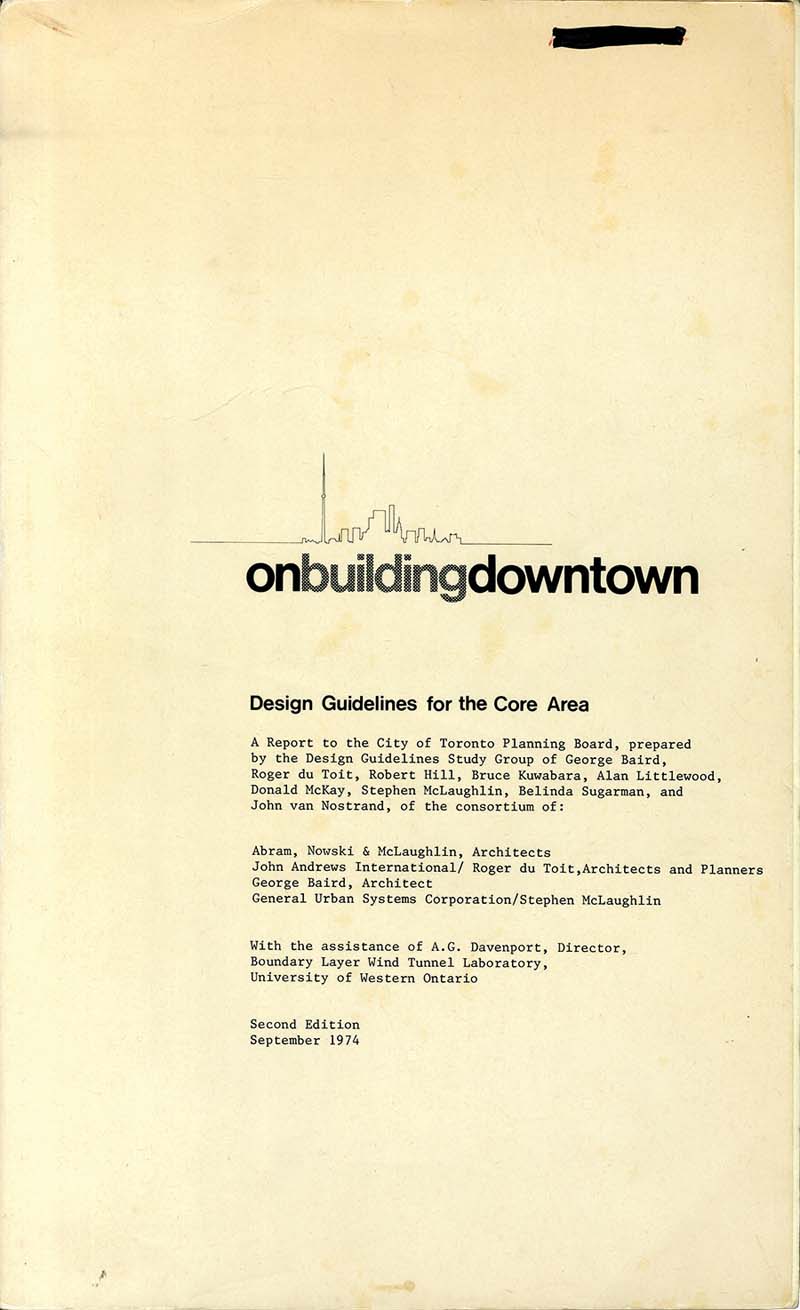

Along with helping on modest design commissions for house additions and a church renovation, soon they and others became collaborators on two of Baird’s most widely respected and influential works. The ground-breaking studies commissioned by the City of Toronto—On Building Downtown and Built-Form Analysis—were the most creative and intellectually rich urban design publications Canada had seen. This is a key theme of the lively and gracious interview Damiani conducts with Bruce Kuwabara, who argues that “Our studies, especially Built-Form Analysis, [showed] that property values could be maintained and that a mixed-use core did not imply less density. Considering that these fundamental objectives have shaped Toronto’s growth over the last forty years, I feel that our studies had an important impact.”

John van Nostrand and Marc Baraness make much the same point in their contributions to The Architect and the Public. Hans Ibelings and Andrew Choptiany assert that “On Building Downtown was a direct and practical application of phenomenological and structuralist concepts in the form of guidelines for densifying Toronto’s downtown core.” Comparing Baird’s work to that of Rem Koolhaas, with whom Baird sparred after The Space of Appearance appeared, they state: “[Baird’s] work is essentially Torontonian […] He has made significant contributions to the field of architectural theory, but it is in his role as a disseminator that he has had the most influence.”

Indeed, the essays and interviews contributed by Baird’s Toronto cohort are the spiritual core of the book, linking Baird’s theoretical interests with his commitment to practice, along with a fascination with urban fabric and the social success of Toronto. Adrian Blackwell offers a finely written survey of Baird’s evolving intellectual passions, from semiotics to post-structuralist theory, plus his reactions to the writings of Robert Venturi and Hannah Arendt. He highlights the importance of Baird’s studies of urban housing typologies and the morphology of the city, as Baird focused ever more on the urban lot as the key unit of understanding how neighbourhoods agglomerate and cities grow. Blackwell proposes that “Baird’s most powerful discovery has been [recognizing the importance of the] intertwined apparatus of public space and private property to architectural and urban theory.”

Having set things in motion, but frustrated by the climate in practice—in the architecture school, and in post urban-reform movement Toronto generally—by the mid-80s Baird took up visiting appointments at American Ivy League schools. He moved to Harvard to teach full-time from 1993 to 1996, consolidating his global reputation as a teacher and critic of architecture. Happily for Canadian architectural culture, he subsequently retuned to become Dean at what later become known as the Daniels School of Architecture, Landscape, and Design.

The 25 years since Baird returned to Toronto are ones when he perhaps most enjoyed the fruits of his labours. His book on Arendt was well-received, if thought by some to have missed its moment (Eisenman opined to me that it was two decades too late for the influence it deserved); it was followed by books on street photography and the collection Writings on Architecture and the City. In 2012, the Daniels School convened a symposium on Baird and his work, and most of the essays collected in Damiani’s The Architect and the Public began as presentations there.

Conclusion: Theory, Practice and Criticism

Because it spans both sides of the Atlantic through a half-century of architectural culture, it might be anticipated that a book like The Architect and the Public would reveal some unexpected larger patterns. A sentiment shared by many of its contributors is that there has been a rise and fall in the estimation of theory by architects, and that things are now at a low ebb, with some referring to a “Theory Age” in the past tense. In his conversation with Daniels ex-Dean Richard Sommer, Baird agrees that it is almost impossible to combine practice with scholarship in architecture schools today. “Theory fatigue had set in,” Baird proposes, and recent years have seen “the gradual displacement of theory from engagement with buildings.”

Harvard GSD’s Michael Hays describes himself as being part of “The Theory Generation.” The same would apply to most of The Architect and the Public’s contributors. In his interview with Damiani, Hays notes how current students “who previously would have studied advanced theory, now spend their time with tech. As a result, a few generations of design students have passed through school with very little teaching or support with regard to critical theory.” Good news for the writers in the book, he notes there is increasing interest in the history of theory, if not its contemporary creation. Consequently, this collection may quickly become one of the best books available summarizing the arguments of the last half century, showing how architectural theories evolved, grew and died—all focused through the lens of Baird’s career. Like many others in the book, Hays thinks Baird’s continuing connection to practice and urbanism has vitalized his theory: “The influence of theory pervades architectural education, even where theory itself is denied. George Baird can claim to have been one of the few to usher in this new imbrication of design research and a kind of ‘theory-in-the-making.’” Hays concludes that “Baird is more aptly described as a highly literary and philosophical architecture critic and commentator, rather than a theorist.”

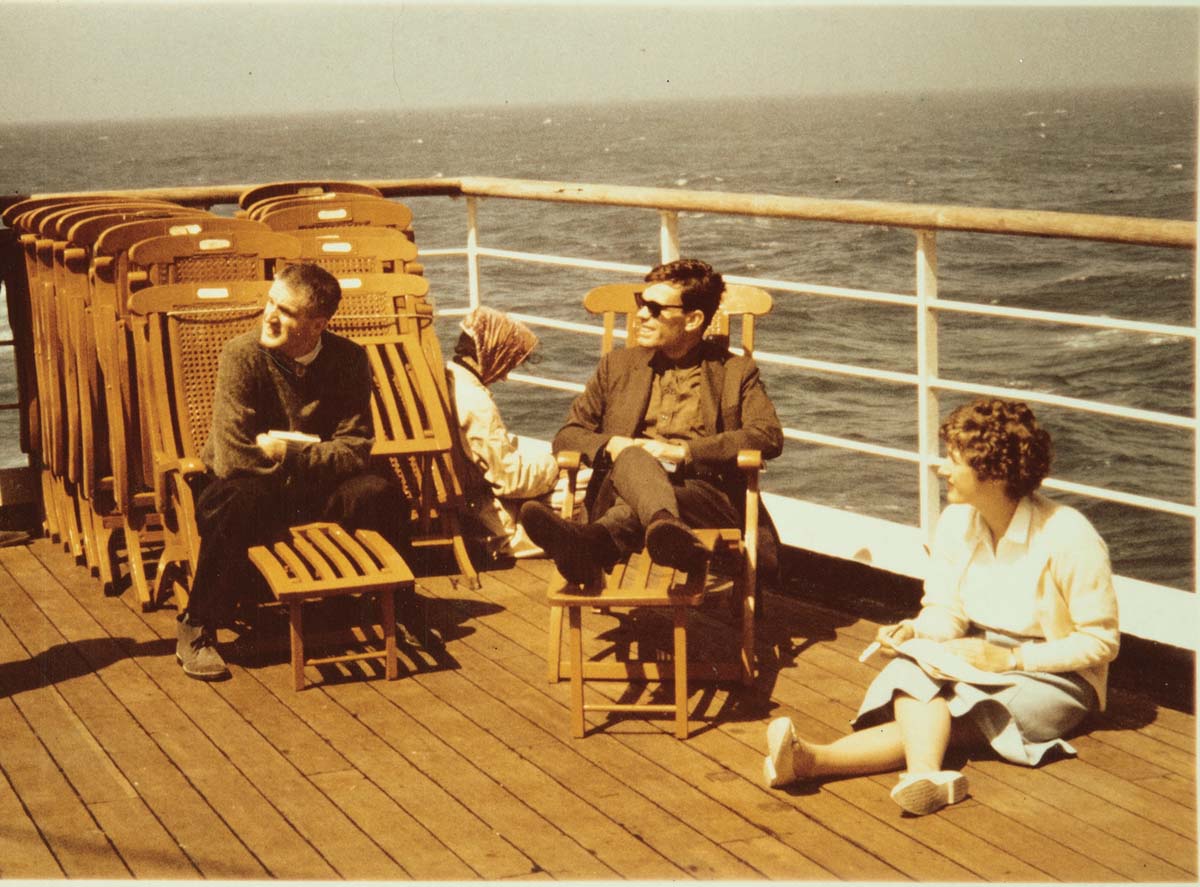

The Architect and the Public is the product of meticulous scholarship by Damiani and his academic colleagues. The book includes a timeline, detailed bibliography and footnotes plenteous enough in length and linkages to inform a full doctoral seminar. Baird is also more the packrat than I ever knew. Seemingly every piece of paper that ever sat on his desk now has a permanent home for scholars to peruse at Calgary’s Canadian Architectural Archive. Taking advantage of this hoard, Damiani’s book is illustrated with dozens of pages reproducing Baird’s studio and seminar outline handouts, posters for talks at prestigious universities, and a colour folio featuring book covers and snapshots of the Toronto architect with students and colleagues, even steaming across the Atlantic to Helsinki in 1959. The book covers the range and substance of Baird’s professional life, ideas, and achievements in stunning detail.

This makes the book’s one gap all the more obvious, and baffling. The Architect and the Public contains no illustration—and almost no mention—of any completed building produced by Baird’s architectural practice, be it his original sole proprietorship, his partnership with Barry Sampson, or its most recent version when they were joined by Jon Neuert. Why? Baird was always frank that he was never the hottest pencil in the firm, but his name was on the door for a half century. Sampson often spoke to me of Baird’s importance as an in-house critic and sounding board as designs evolved at their firm. As this book was in the works for nearly a decade, I am disappointed that there was no essay commissioned from Sampson while he lived, and barely a mention of his passing. One of the essential architectural arts is criticism, which is equally crucial for design studio reviews, the give-and-take of producing buildings, and writing for books and journals. Do theorists underestimate criticism, after belittling it as mere application, shifting into a critical mode of their own?

I am quite proud to claim George Baird as an architecture critic who applied his judgment and intellect to understanding buildings, and who catalyzed public spaces of equity and consequence. I would go on to propose that criticism remains much more important to architects than theory, from which it so obviously draws. Baird’s role in practice, in devising urban design rules for Toronto, in his studio and in classroom teaching, and especially in his writing (where nearly every essay links to a specific constructed building or public space, the kind of connection rarely made by theorists of his era) is much more that of the critic than the theorist. Even lining up the contributors to Meaning in Architecture was more the act of a critic-curator than a systems-spawning theorist, and ditto for the unusually inclusive lecture series and academic conferences Baird organized—not to mention the salon-like dinners he and his food writer wife Elizabeth have often hosted. He is responsible for more friendships and convergences of ideas than any architect ever to call Canada home. There is an art to such linkages, and George Baird is a maestro.

I have to disagree with Peter Eisenman. Baird’s magnum opus, The Space of Appearance, was not too late when it was published in 1995. Given the intense current needs of cities and citizens, it may have actually arrived too early. More so than any time in the past few decades, architecture is overdue for an engagement with politics. Baird’s application of Arendt’s ideas on equity and public space is an ever-optimistic way forward, his real contribution to architecture. With many of us losing access to all that is public during pandemic lockdowns, there has never been a stronger market for focused thinking on how to shape a new urban sensibility. After a half-century hovering in the wings of world architecture, and true to his on-the-stage and off-the-stage career, George Baird may be about to make a re-Appearance.

The Architect and the Public: On George Baird’s Contribution to Architecture is published by Quodlibet, Rome (2019).

Vancouver-based architecture critic Trevor Boddy contributes the anchor essay “Enclaves of Invention” to the monograph D’Arcy Jones Architects, forthcoming from Dalhousie Architectural Press. He was co-curator of the 2014 “Critical Junctures” global gathering of architecture critics at London’s V&A Museum, which included George Baird.