Addressing climate change through advocacy, policy and planning

The symbiotic relationship between municipalities, advocacy groups, and the real estate development community is a complex ecosystem critical for the design community to understand when addressing climate change through advocacy, policy and planning.

Architects, landscape architects and urban planners are influential brokers to facilitate change in the built environment, yet we rely upon experts and researchers who make it their business to provide convincing background data and policy alternatives for legislators. When the agenda is targeting net-zero strategies, positive change happens when cities can push the climate agenda forward through clear incentives for developers, often through regulations that restrict underperforming buildings while encouraging highly efficient retrofits and new construction. To this end, the real estate community has the greatest opportunity to influence—and deliver upon—market demand for buildings that can reduce their greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions to zero. The symbiotic relationship between municipalities, advocacy groups, and the real estate development community is a complex ecosystem critical for the architecture and planning community to understand when addressing climate change through advocacy, policy and planning.

We felt the best way to unpack this issue was to invite three Toronto-based leaders representing a real estate company, a non-profit agency, and the City of Toronto for the final episode of our first season of SvN Speaks: a series of climate-positive discussions launched during the summer of 2022. Our guests included Julia Langer, Jenny McMinn and Jane Welsh. Langer is the CEO of The Atmospheric Fund (TAF), a non-profit corporation endowed by the City of Toronto, the Province of Ontario and the Government of Canada to advance low-carbon solutions for cities. McMinn is the Managing Director of Urban Equation and Partner of Innovation and Impact at Windmill Development Group, providing both real estate development and sustainability advisory services across North America. Welsh is the Project Manager of the Environmental Planning unit of Toronto City Planning for the City of Toronto. She is responsible for creating new solutions to address sustainability, climate change and resilience. Welsh’s achievements include the development of the Toronto Green Standard, the Green Roof Bylaw, and Official Plan policies for Environment and Climate Change. While all three guests have never worked together on a project, they have invariably collaborated with each other during their careers. As our conversation unfolded, it became clear just how important their complementary skill sets and world views inform each other’s position in advancing the climate change agenda.

We felt the best way to unpack this issue was to invite three Toronto-based leaders representing a real estate company, a non-profit agency, and the City of Toronto for the final episode of our first season of SvN Speaks: a series of climate-positive discussions launched during the summer of 2022. Our guests included Julia Langer, Jenny McMinn and Jane Welsh. Langer is the CEO of The Atmospheric Fund (TAF), a non-profit corporation endowed by the City of Toronto, the Province of Ontario and the Government of Canada to advance low-carbon solutions for cities. McMinn is the Managing Director of Urban Equation and Partner of Innovation and Impact at Windmill Development Group, providing both real estate development and sustainability advisory services across North America. Welsh is the Project Manager of the Environmental Planning unit of Toronto City Planning for the City of Toronto. She is responsible for creating new solutions to address sustainability, climate change and resilience. Welsh’s achievements include the development of the Toronto Green Standard, the Green Roof Bylaw, and Official Plan policies for Environment and Climate Change. While all three guests have never worked together on a project, they have invariably collaborated with each other during their careers. As our conversation unfolded, it became clear just how important their complementary skill sets and world views inform each other’s position in advancing the climate change agenda.

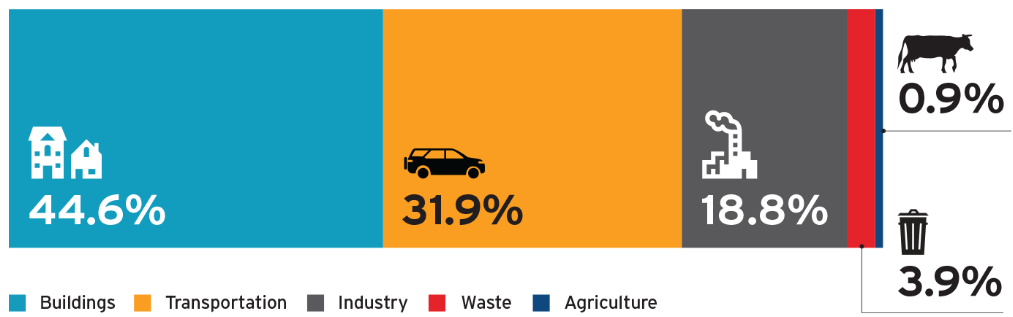

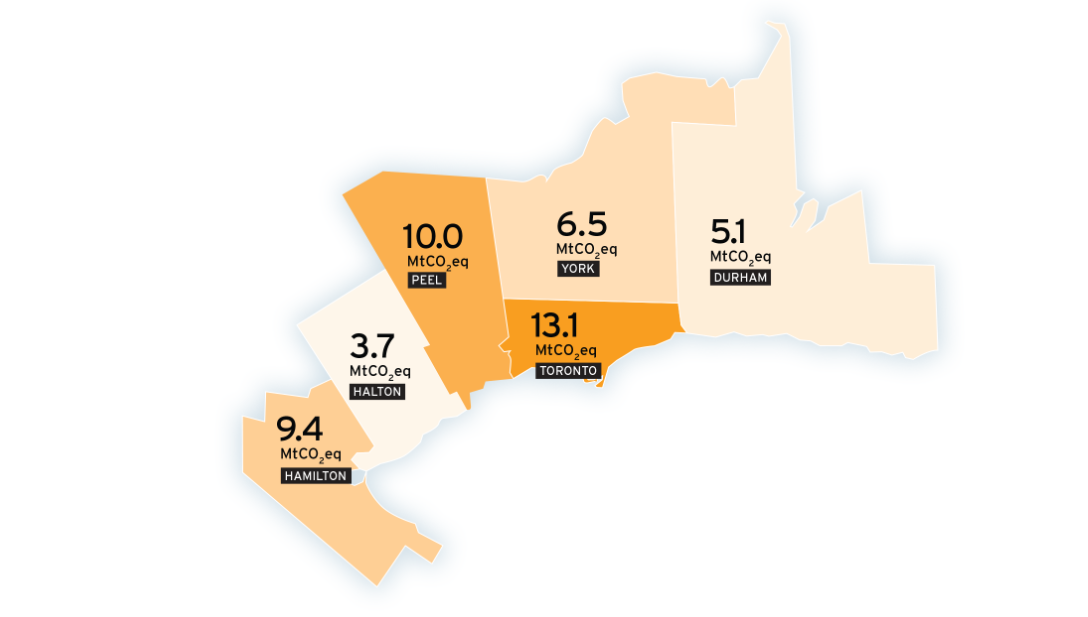

As we strive to reduce global GHG emissions, it is important to note that buildings contribute, on average, 40% of GHG emissions annually. According to TAF’s carbon emissions inventory, that figure is 44.6% of all GHG emissions for the Greater Toronto Hamilton Area (GTHA). To effectively transition towards a post-carbon future, new building stock will continue to play an essential role. Transportation is the next priority, contributing to 31.9% of the GTHA’s GHG emissions. While encouraging more electric vehicles on our roads is not directly the purview of architects and planners, making cities less reliant on automobiles provides a distinct area of focus for our profession amidst the global climate crisis.

Post-Carbon Leadership and Advocacy

What can a city like Toronto do to encourage low-carbon building forms and construction in urban areas? How can architects facilitate dialogue between the real estate development community and the City to promote effective post-carbon policies? And what are the current opportunities to bring our objectives to scale so that we can meet 2030 targets, ultimately having Toronto become a zero-carbon city by 2040?

As CEO of TAF, Langer describes her organization as a “skunk works,” a term often used in the business world—particularly engineering- and technical-related contexts—to describe a group within an organization given a high degree of autonomy and unhindered by bureaucracy. TAF is in a privileged but crucial position to operate with an endowment to explore the many carbon-reducing possibilities while identifying and supporting the players that need to be involved. TAF helps advance low-carbon solutions through policies that provide capacity building where there is carbon reduction potential. Every year, they publish a definitive inventory in the GTHA that examines where those opportunities are, determining progress and ensuring proper alignment with programming, policies and investment opportunities. “Buildings are nearly 50% of the emission profile. Most of that is existing buildings and will increasingly be new buildings,” explained Langer, adding, “We are looking at both retrofits and new buildings. We are looking at building owners, investment and capital markets communities, cities, and utilities.” TAF sits between the developers who need to drive consumer demand for low-carbon buildings and policymakers, where Langer emphasized the reality of the consumer market and developer timelines, adding, “We need to work with developers early on. In a hot condo market, if you spend $2,000-4,000 more per unit to build a better building, they’ll buy the cheaper condo down the street.”

To help lower costs for the developer, TAF developed a finance mechanism for developers. Its Green Construction Loan program offers incremental financing up to $2,000,000 to make a building at least 25% more energy efficient than the Ontario Building Code at the time. The condo owners repay the loan because they benefit from the energy savings. The program’s success provided proof of concept for the City of Toronto, supporting their confidence to raise overall building efficiencies through its Toronto Green Standard. “You have to work with the players who are willing to ‘make it a go’ and then translate that into a policy or a mechanism that makes sense for everyone,” Langer said. “This is one example where you can go from demonstration to de-risking to socializing it within the marketplace, eventually making it a policy that ensures everybody is on board. Then, you can evaluate the results.”

To explain the value of the City of Toronto’s partnerships with organizations like TAF and collaborations involving the University of Toronto on low embodied carbon research, Jane Welsh discussed how the City works with developers who experiment with and comment on policy initiatives destined for further refinement by the City. Welsh discussed some leading real estate developers like Minto, Tridel and Daniels, who have engaged in an iterative learning process. Welsh explained, “Because there are cost implications when setting up a pathway for developers to work towards net-zero goals by 2030, we are always looking to provide clarity for them and to help socialize expectations in the marketplace to create consumer demand. Metrics are essential to help speed up adoption. And changing new building standards raise the expectations for existing buildings because that becomes the model you work toward.”

Too often, developers are criticized for not doing enough to build low-carbon buildings. However, as Jenny McMinn said, “One key thing developers are looking for is clarity of expectations so that risk can be managed and expectations met.” For developers like McMinn, it is not just the environmental aspect but also the social component that goes into her planning processes. These two factors are intertwined in arriving at a post-carbon solution and as a critical component to meeting the increased consumer demand for livable communities. McMinn thinks strategically and holistically. “We partner with key stakeholders, group policymakers, and other advocates at the ownership level. This commitment involves hard work requiring creative thinking and design to achieve an end product where we can achieve a Toronto Green Standard Tier 2 or beyond building without sacrificing lifestyle.”

McMinn draws from her experiences with many Windmill projects where the idea of a strong narrative includes experiences such as connections to local food production, community partnerships, or district energy production such as geothermal or waste heat recovery systems. As often is the case, developers have opportunities to create places that address serious environmental issues while realistically achieving livable low-carbon communities. McMinn cited the One Planet Living® framework developed by the UK-based social enterprise Bioregional—a process where communities are defined as being both socially inclusive and low-carbon. This framework further opens up several opportunities to align policy and advocacy with built results. Ultimately, McMinn emphasized, “the critical component here is ‘partnerships.'” Like the City of Toronto, Windmill also relies on arm-length organizations like TAF to help speed up the adoption of their low- or zero-carbon developments (TAF provided a “green construction loan” for a Windmill project in Ottawa). But McMinn is also the Managing Director of Urban Equation. This advisory firm is separate from connected to Windmill while advancing a green agenda, both as a service to municipalities and other developers while boosting in-house advisory and research capacities within Windmill.

Speed and Scale

Speed and scale are essential concepts to address when determining the critical gaps to close as when seeking new ways to improve the efficacy of low-carbon project delivery met through strong policy, finance and funding mechanisms. One important idea to emerge from our conversation relates to the electrification agenda. Langer quickly pointed out that GHG emissions went way down when we finally phased out coal-fired plants in Ontario at the end of 2014, but since then, GHG emissions have been pretty much flat. “If we want to reach our 2030 targets, we need a 7% reduction yearly, every year. We have to electrify our home heating and transportation infrastructure,” declared Langer, noting how the utilities will have to play a more prominent role in helping developers—and not just individual homeowners—achieve GHG emissions targets through electrification. Langer pointed out that Toronto Hydro recently published its first climate plan. At the same time, the Provincial government needs to de-regulate utilities and allow new market entrants to supply electricity, eventually creating enormous opportunities for the development community and ushering in partnerships between innovative companies and utilities.

The big question about the electrification agenda is whether our current electrical grid has enough capacity. Toronto Hydro and other local utilities must emerge as much stronger advocates while managing the risks of increased electrification. McMinn remarked, “there is a need to reduce the demand for energy as one switches over to electricity. It’s a two-step solution on the building front–switching supply over to electricity while also driving down the amount of energy that buildings need in the first place.” Langer added that the business case for electric heating and using very efficient heat pumps is very strong on the new construction side. On the retrofit side, the business case is less convincing, though completely doable with the appropriate structured financing.

Including community: designing beyond individual developments

We often speak about individual buildings and consumers, forgetting about community developments’ larger role in reducing GHG. Windmill and other developers, including Dream Unlimited and Theia Partners, are working on Zibi, a major multi-stage project straddling the cities of Ottawa and Gatineau. Windmill initiated the Zibi development, achieving all the entitlements and approvals required for Canada’s first One Planet Living community, including the establishment of a District Energy Strategy (DES). The DES is the first in North America to use post-industrial waste recovery within a master-planned community whereby Windmill helped create an equal partnership between Hydro Ottawa and Zibi to provide net-zero carbon heating and cooling for all Zibi tenants, residents and visitors in the 34-acre development. The DES will be managed over the long term, and its scale and purpose make a lot of sense, given that so much of the neighbourhood is condo units where developers build and sell them but are not around to recoup the energy savings. The DES is a built-in revenue stream of little benefit to a condo developer but significant to the residents. As McMinn pointed out, “Zibi’s DES is another way to think of the provision and sale of energy as a business where using wasted heat from the onsite industrial plant is an energy gain that can be capitalized upon.” Windmill recognized the opportunity and understood that Ottawa Hydro’s business models are changing, so the discussion was, “the world is changing and here is an opportunity to work together and create a district system.” The massive benefit to Windmill, its partners and the eventual residents are that a reputable known entity runs the day-to-day business of selling energy.

Langer added that similar models to Zibi’s DES are being studied elsewhere. For example, the Hamilton Chamber of Commerce received a two-year grant (2019-2020) from TAF to identify opportunities to increase waste heat recovery among steel manufacturers operating in Hamilton’s Bayfront Industrial Area. Other ideas include understanding how to mine heat from data centres, or simply having two or more buildings share their varying heat loads throughout the day where an east-facing building could transfer excess heat to an adjacent building and vice versa. Citing New York City’s Local Law 97 (see SvN Speaks Episode 1), Langer mentioned how a successful piece of planning legislation is driving an entire building industry sector to ramp up and respond to more stringent low- or zero-carbon regulations. Welsh agrees, citing the City of Toronto’s Official Plan and other planning instruments that have the potential to create district energy production or generate renewables onsite. Truly low-carbon building energy strategies are within reach.

Addressing climate change through advocacy, policy, and planning is complex, but solutions are available. The biggest lesson to realize is the ongoing need for organizations like TAF to nudge, support and provide innovative options for municipalities and real estate developers to consider. And we must work with the private sector to test and help refine more stringent policies that will ensure our cities can reach their net-zero targets before it is too late.

SvN Speaks Episode 6.mp4 from Sean Mackay on Vimeo.

@AuthorBio: Drew Sinclair is the Managing Partner of SvN Architects + Planners.

Additional Resources:

Toronto Green Standard https://www.toronto.ca/city-government/planning-development/official-plan-guidelines/toronto-green-standard/

Official Plan Environment and Climate Change policies: https://www.toronto.ca/city-government/planning-development/official-plan-guidelines/official-plan/official-plan-review/