Decolonizing the Design Process with Five Indigenous Land-Based Paradigms

By reconsidering our approach in how we teach design and returning to land-based practices, students may come to see the land as their partner—as a teacher.

“… a space that is somehow meaningfully organized and on the very point of speech, a kind of articulated thinking that fails to reach its ultimate translation in proposition or concepts, in messages … the various landscapes, from frozen inland wastes to the river and the coast itself, speak multiple languages … and emit a remarkable range of articulated messages.”

– Peter Kulchyski, from Like the Sound of a Drum: Aboriginal Cultural Politics in Denendeh and Nunavut

Over the last decade, as faculty members and instructors at the University of Manitoba, we have begun to use our classrooms and design studios to engage in partnerships with Indigenous communities. Our aim has been to develop meaningful research and studio projects to explore how the design disciplines can learn from—and contribute to the needs and ambitions of—Indigenous communities. Through this intent, the projects have aimed to position Indigenous communities as a guiding voice, opening the way for those communities to shape the goals of the studios, and ensuring that the outcomes always serve in a good way.

This work has been an opportunity for us to reconsider how contemporary architectural education can evolve past the colonial frameworks that determine much of the present discourse. We believe that these studios are a platform for exchange; a back-and-forth gathered relationship between our programs, students, instructors, and Indigenous community members. Rooted in both Indigenous and Western worldviews, these studios have challenged traditional academic models for teaching to include Indigenous ways of knowing, making, and doing, to engage with the human and more-than-human worlds. (1) In doing so, we ask: how can we decolonize design practices and create a reciprocal praxis for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous practitioners, students and scholars?

To answer this question, we have begun to develop a decolonial and unsettling design framework to help guide both students and instructors to work through an Indigenous lens. This often requires one to “see with two eyes,” or learn from the strengths of both Indigenous and Western knowledge, for the benefit of all. By bundling a philosophical and dialogic collaboration with both Indigenous ways of knowing and Western schools of thought, we create a mutually beneficial and synergistic relationship as a way forward.

In the studios, students begin to understand that Canada’s settler-colonial practices have created lasting and devastating impacts on Indigenous communities, disconnecting many peoples from their roots, traditions, and ceremonies. They learn first-hand about how past and current social and political policies were designed to create the erasure of Indigenous peoples from their land, culture, and stories. We find that only once students come to understand these realities, can they begin to question how design practices can help address these systemic injustices that persist today.

Foundational to these studios is the idea that knowledge is all around us, rooted most deeply in place and the people and communities with whom we serve as designers. As such, these studios prioritize teachings offered from cultural guides, traditional languages, grassroots organizations, people with lived experiences in communities, and work on and with the land itself. This (re)framing of where knowledge comes from is the first step in decolonizing and (re)mapping the design practice. (2)

The following Five Indigenous Design Paradigms have evolved from this ongoing work, as a tool to help students in this learning process. They can be used as a sequential or non-sequential praxis that augments the typical design processes. The paradigms are not meant to replace existing processes, but rather become rooted in current methods to give attention to place, intuition, listening, visions, reciprocity, and sharing a good story. This is an iterative process: a back-and-forth, forwards and back. It can be cyclical, or in constant motion. The main purpose is to create a sense of awareness in the individual, making them available to the teachings of the land and community, to promote creativity, and to remind them to always ask, “How am I giving back?”

Five Indigenous Design Paradigms

Da na ka mi gad: It takes place, happens in a certain place

From daN – There is a certain place; Akamig – land, ground, landscape, event; ad – it is in a state or condition.

We should ask ourselves: What is place?

Mohawk scholar Sandra Styres explains that by occupying the emptiness of space, by being present, space becomes “placeful.” Mohawk scholar Vanessa Watts notes how Indigenous societies are reliant on particular and powerful relationships to land and place. Watts observes that human thought and action are derived from a literal expression of particular places and historical events. According to Watts, the agency that place possesses for Indigenous peoples can be thought of as similar to the agency that Westerners locate in human beings. Moreover, Indigenous peoples are extensions of the very land they walk upon, and have an obligation to maintain communication with it. In Indigenous design, place should be defined by culture, spirit, people, the land, language, other beings, time, and experience. To truly understand a place, you must subject yourself to it, be immersed in it, and commit to the experience it offers.

The position in this paradigm is about relationship-building and taking time to understand. It is about acknowledging your uniqueness and where your gifts lay, and allowing a particular place to speak to your practice. Through kindness and openness, the place opens up in distinctive ways, helping to remove the perceptive barriers that separate us from the natural world, forming the foundation of our creative acts.

When we began exploring this paradigm, we engaged with our Anicinabe cultural guide Calvin Skead from Wauzhushk Onigum, located on Treaty 3 in the Lake of the Woods area. He sat with us and generously shared his understandings of gift-giving and what it means to work in a “good way.” After, to honour the land, we prepared offerings for the wolf that lives on the site, the trees, the small creek running through the property, and for our ancestors in the open fire. Our time with Calvin set the tone: it was disarming, and made us vulnerable and available to the site and the experiences we were about to encounter. He taught us to understand a place by slowing down, having patience, listening, and connecting through our experiences.

We believe an essential part of understanding a place is connecting with it, witnessing it as an animate being. As we see it, preparing and offering gifts to the land builds relationships with the natural world. It creates a sense of openness that moves us to consider, in Calvin’s words, “all our relations.” Through habits of kindness and connection, we believe that a shift in mindset has the power to build relationships with place, and to profoundly change how we exchange with the environment and understand our relationship to it through our design practices.

An do tan: Listen for it; wait to hear it.

Land is more than the diaphanousness of inhabited memories; Land [with a capital L] is spiritual, emotional, and relational; Land is experiential,(re)membered, and storied; Land is consciousness—Land is sentient. Land refers to the ways we honor and respect her as a sentient and conscious being … a philosophical construct.

–Sandra Tyres, from “Literacies of Land, Decolonizing Narratives, Storying and Literature”

This paradigm is about spending time on the land, connecting with the place, and being guided by your intuition. It is about working in whatever way you desire, letting your heart and impulse reveal new possibilities. Andotan promotes working to engage your inner creativity, inspiring and connecting to the process while rooting yourself mentally, emotionally, physically and spiritually in place and in the land.

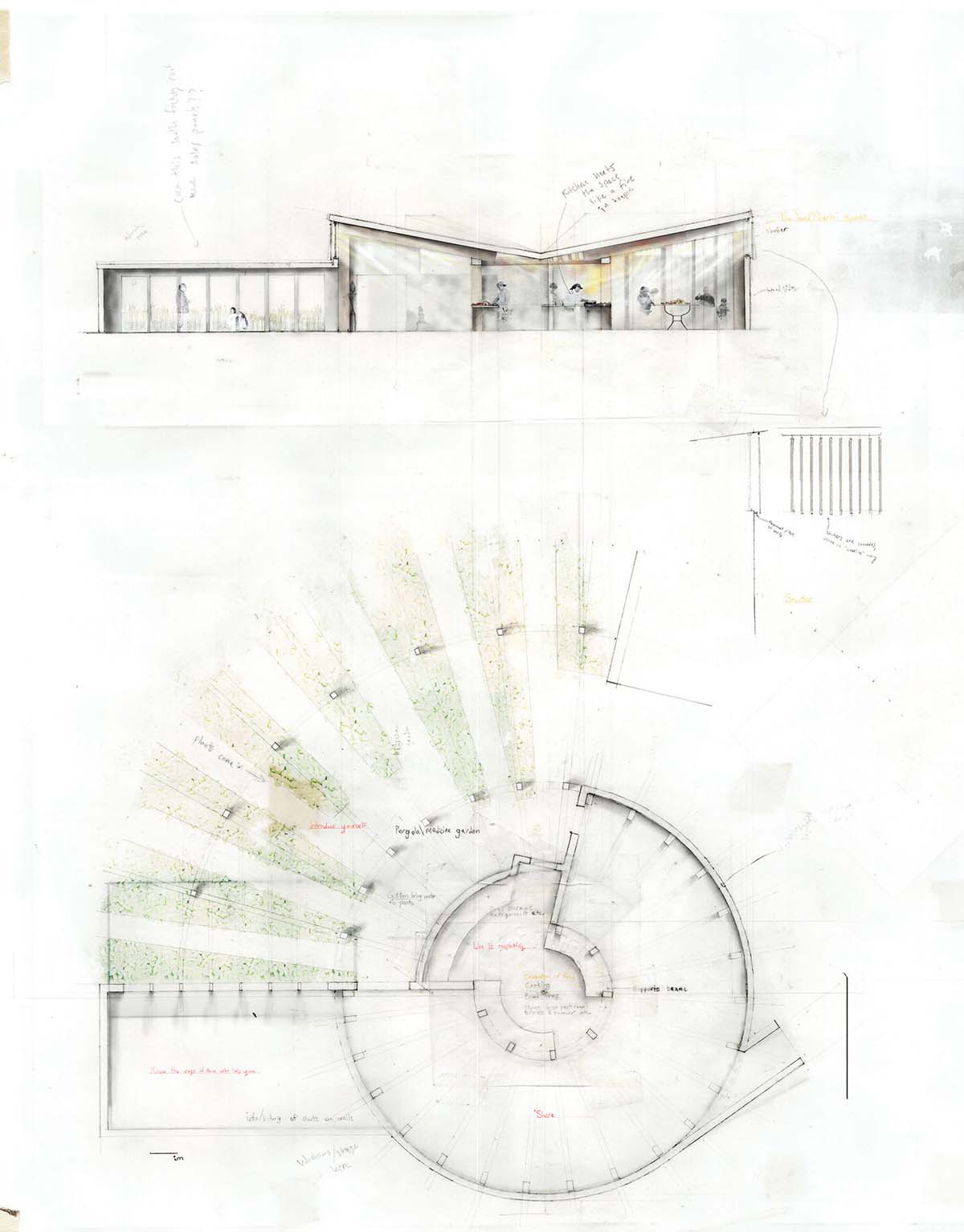

In one studio, we worked with a regional Indigenous community regarding the topic of food sovereignty. Students were asked to develop site plans from the stories they heard during our community visits. Sixteen students hung visions on the walls of the community centre. Instead of the typical site drawings and designs, one student had allowed the process to lead her to make a textile map and a book of illustrations, which shared her reflections on the stories she had been told by the community. You could tell she was unsure about what she had prepared, but by trusting her intuitive process, she had accomplished what she felt was right—and the community members embraced it. The openness of her work provided

an opportunity for the community to dream about the project with her. The conversations that followed the presentation of her work profoundly influenced the remainder of her studio project, and provided a depth of engagement with the community that was only made possible through her unique approach to the work.

We believe that Andotan is the first declarative work, where students and practitioners reveal that they have heard something. During this process, knowing when to slow down is essential. Being patient and listening—moving at a pace slow enough so that you can receive the teachings.

Ba waa ji gan: A Dream, A Vision

I have lived here longer than where I was born

I walk along its concrete trails

Paths have led me through back alley dreams

Still my visions take me back

That place where the river blessed me

I could dive down deep within that clear cold water

Stretch my arms out to touch bottom …

-Duncan Mercredi, from “This City”

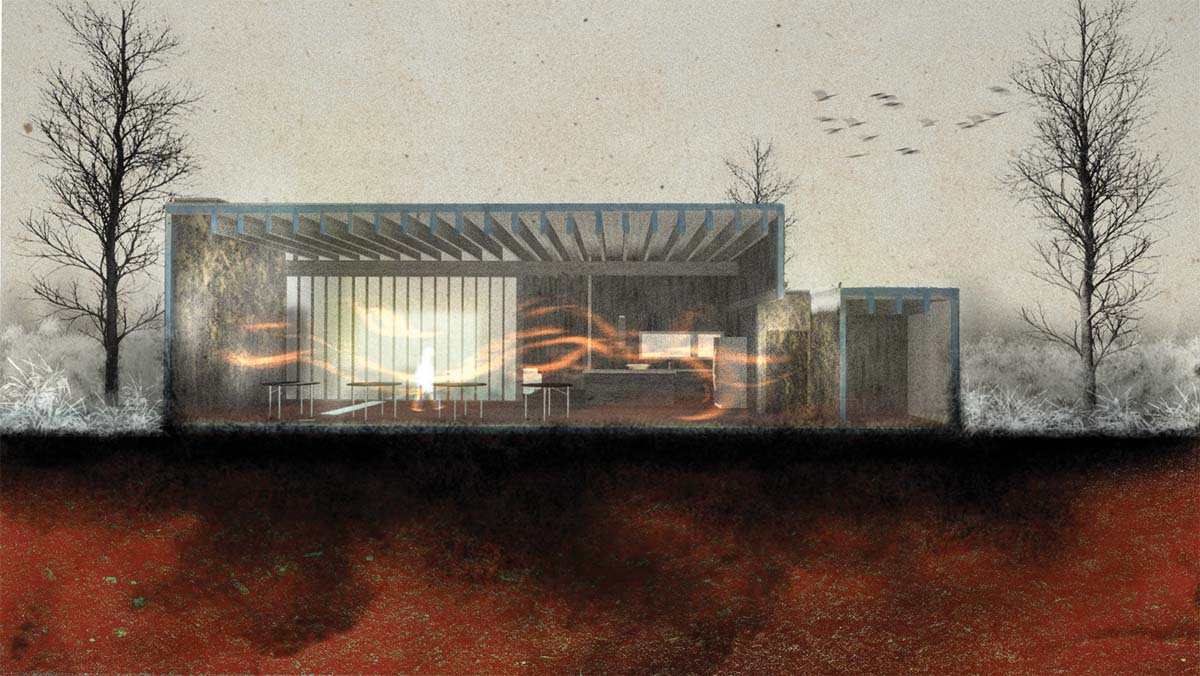

Through listening, dreaming and following your intuition, Bawaajigan is the realization of Andotan. It suggests that by performing this intuitive and reflexive practice, a vision will appear. In design practices, intuition is often associated with a design impulse that lacks accountability to the broader complexities of a project. However, Bawaajigan suggests that as we recognize ourselves to be creative beings who sense the world in conscious and unconscious ways, design concepts or ideas will arrive: not through random association, but through an attentive awareness of the fuller realities of a project. An understanding of what matters that can only be achieved after one has heard the teachings from Andotan and digested what they mean to the individual. It is by approaching the process with humility and openness that the dream or vision will appear. This paradigm opens the designer to prioritize concepts that develop from one’s nature and from one’s intuitive response to a project, while avoiding the objective mode of creating in a more solution-oriented manner.

In these studio projects, one of the main challenges is to help students realize that designs can arise in many ways, and that one cannot force a design to happen. Instead, one has to be patient for the process to reveal itself. The dream or vision that Bawaajigan offers is not so much a manifestation of a design itself, but rather a set of relationships that reveal themselves in order to help guide the design direction—a way of moving forward, in a good way.

In one case, a student was struggling in how to manage and apply the numerous stories and teachings she had been exposed to in the design process. Rather than providing clarity on how to move forward in the project, these teachings revealed more complexity to the relationships of the site and dynamic conditions that the project would need to engage with, if it were to provide a meaningful gift to the community. After some conversation with members from the community, the student came to understand that her job was to not simplify the complexity or fit it into a design; instead, she needed to embrace it. She found a way of drawing the site in which the individual teachings and site conditions could be layered, becoming situated against, on top of, and within each other, revealing the nature of the landscape in which she was to work. This approach allowed her to view indeterminacy as the common ground of the site. Her design direction became a negotiation of these complexities, and the design of her project itself arose from this negotiation of site, circumstance, and balancing the layers revealed in the drawings and teachings.

Meshk wad: In Turn, in Exchange

As a process of humility, Meshkwad combines two directions. The first is to understand the gifts that we as designers can give, and the second is to understand what gifts will benefit our community partners. Sometimes, what we design can be problematic or even a burden. It is essential to turn into the work, and exchange gifts that both fit our abilities and benefit all.

As one studio progressed, a student came to ask, “How we can design with nature?” Through the work, she realized that the first step is to see nature as an animate being, participating as a partner in the process. Inspired, she rewrote a section of the National Building Code and titled it “Natural Being Flows,” translating nature’s voices into human legislation. Her text describes all beings as free and equal, and entitled to recognition, protection, and rights.

We believe that gifts should go beyond the intention. As designers, we should ask ourselves, what are we giving back? Consider how the exchanges of dreams and visions both from our partners and from us as designers inspire, empower, connect with people and places, connect with the land, and manifest materially. Design is an action; it is a result-oriented exchange between partners. It should be cyclical: in motion and ever-changing, rather than the fixed outcome of a linear process. We should always return to the term Meshkwad. Design can be seen as a result-oriented exchange between partners, similar to the way that physical gifts are exchanges of material objects. But in many Indigenous cultures, gifting is a sharing of wealth meant to keep goods in movement between owners. The gifts of design can similarly be seen as cyclical, in motion and ever-changing. Design is most powerful as an action, rather than as the fixed, final outcome of a linear process. We should always return to the reciprocity inherent in the term Meshkwad.

Naa go toon: Make it Show, Reveal it

The success of a project should be revealed in its ability to tell a good story. Beyond its superficial value as entertainment, the powerful capacity of storytelling is the process of opening to new opportunities. In design, storytelling happens when you acknowledge the journey and bring that story through the project. Again, as a gift, you have arrived amid a historical trajectory, and together in partnership, you are offering a continuation of the narrative after your work is done.

The story becomes the materialization of the process. It is communicated through the design and presentation of the project. Storytelling is a decolonizing process, where students and designers can listen to themselves, communities, the land, and the language. What do we want together for the future, and what stories will get us there? The magic in storytelling is revisiting the stories as they become an essential part of your nature.

Storytelling ignites Indigenous land-knowledge. As scholars Jo-Ann Archibald (Q’um Q’um Xiiem), Jenny Bol Jun Lee-Morgan and Jason Santolo explain, storytelling is an act of decolonization, communicating through generations and memories in opposition to the exclusive and dominant Western “story” that has emerged from ideologies of colonialism. Under the umbrella of decolonizing research, storywork “aspires to re-cover, re-cognize, re-create, re-present, and ‘re-search-back’.”

Through stories, one can see parts of their own consciousness reflected, allowing for learning and growth. Through stories, designers can engage with the Indigenous and settler public to communicate worldviews and artistic aesthetics. These notions can lead to the decolonizing of our practice while generating new and shared knowledge.

Conclusion

We are often asked: how can non-Indigenous researchers engage and take on these Indigenous design paradigms? Our answer is: if students and designers are working through a relational understanding of place while engaging respectfully with Indigenous knowledge and Indigenous peoples, we believe these paradigms can assist in reconciliatory actions.

Grounded in reciprocity, Indigenous worldviews acknowledge the land as sacred. As designers and instructors, we believe the sacredness of the land must be considered in our pedagogy. By reconsidering our approach in how we teach design and returning to land-based practices, students may come to see the land as their partner—as a teacher.

We must remember that motion backwards can be just as important as going forwards. We have encouraged our students to think while in motion, to consider Margaret Kovach’s idea of “giving back”: producing research processes that benefit the community in some way, and do not cause harm. Cree scholar Shawn Wilson reminds us that logic does not need to be linear. On the land, with the environment, with the space between people, it is always about relationships—and ultimately about telling a good story while sharing our gifts.

In our journey to define an Indigenous design praxis, we envision these emerging design paradigms as a decolonizing guide for practitioners and students alike. It is our hope that Indigenous and non-Indigenous designers, planners, interior designers, landscape architects, and architects can apply these paradigms to develop and practice working methods rooted in reciprocity, respect, and care for the land. The aim of these paradigms is to inspire designers to achieve a more profound creative process, and to work towards allyship with Indigenous peoples on the land in a good way.

Shawn Bailey is a member of the Métis Nation of Ontario and a registered architect. Shawn is an Indigenous Scholar at the University of Manitoba in the Faculty of Architecture and the Price Faculty of Engineering. Shawn’s newly founded design firm and research studio, Grounded Architecture, is committed to community-driven projects and delivering architecture through storytelling.

Honoure Black is a White settler woman, mother, partner, instructor, and PhD Candidate in the Faculty of Architecture and the School of Art at the University of Manitoba, on Treaty One Territory. Her research and teaching are transdisciplinary, rooted in art history, Indigenous and settler studies, and environmental design. One of her interests is to work towards decolonizing research and practice within the fine art and design disciplines.

Lancelot Coar is a White settler man and father who has the privilege to live and work on Treaty One Territory. He is an Associate Professor in the Department of Architecture at the University of Manitoba, and a PhD candidate at Vrije University, Brussels. Lancelot’s research in this area focuses on exploring how to promote design sovereignty with First Nations communities by building relationships through collaborative design studios and land-based research initiatives.

The authors would like to thank: Calvin Skead, The Community of Brokenhead Ojibway Nation, Prof. Shirley Thompson and members of the Mino Bimaadiziwin Partnership, Prof. Alex Wilson and members from the One House Many Nations project, Making the Shift Grant, the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, Reanna Merasty, Danielle Desjarlais, Jason Surkan, Aliyah Baerg, Tara Fuller, Kitty Hong, Jelene Pugoy, Nicholas Lupky, Shane Patience, Ariana Streu, Michael Wu, Sabba Rezai, Tymon Melnyk, Brooke de Rocquigny, Derelyne Raval, Rebekah Enns, Lauren Bennett, Max Sandred, Mackenzie Jackson, Teresa Lyons, Hannah Thiessen, Kirsten Wallin, Stacey Berrington, Micaela Stokes, Kate Sherrin, Chelsea Colburn, Rhys Wiebe, Nicholas Basford, Ali Impey, and Natalie Pambrun.

1 Inspired by Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweet Grass (Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions), 2013.

2 The term (re)mapping is inspired by the Native feminist notion of (re)mapping spaces on the land. The concept of (re)mapping unsettles and reorganizes bodies, and both the social and political landscapes. Mishauna Goeman explains: “(re)mapping is not just about regaining that which was lost and returning to an original and pure point in history, but instead understanding the processes that have defined our current spatialities in order to sustain vibrant Native futures.” See Mishauna Goeman, Mark My Words: Native Women Mapping Our Nations (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013).

Bibliography and Suggested Readings

Archibald Jo-Ann (Q’um Q’um Xiiem), Indigenous Storywork Educating the Heart, Mind, Body, and Spirit, Vancouver: UBC Press, 2008.

Battell Lowman, E. & Adam J. Barker in Settler, Identity and Colonialism in 21st Century Canada, Winnipeg: Fernwood Press, 2015.

Denzin, Norman K., Yvonne S. Lincoln and Linda Tuhwai Smith, eds., Handbook of Critical and Indigenous Methodologies, Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 2008.

Goeman, Mishauna, Mark My Words: Native Women Mapping Our Nations, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013.

Mercredi, Dunacn, This City (Except), 2008. Clarise Foster, CV2 Magazine editor, “An Interview with Duncan Mercredi”, Manitoba Arts Council Website, Accessed July 2021, http://winnipegarts.ca/wac/news-article/an-interview-with-duncan-mercredi

Simpson, Audra, Mohawk Interruptus, Political Life Across the Borders of Settler States, Durham: Duke, University Press, 2014.

Simpson, Leanne Betasmoke, We Have Always Done, Indigenous Freedom Through Radical Resistance, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, Accessed on July 2021, http://www.trc.ca

Tuck, Eve and Marcia McKenzie, Place in Research, Theory, Methodology and Methods. NYC: Routledge, 2015

_________ and Wayne K. Yang, “Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor”, Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society. Vol. 1, no. 1, 2012, pp. 1-40.

Tuhiwai Smith, Linda, Decolonizing Methodologies, Research and Indigenous Peoples, Second Edition, London: ZED Books, 2012.

Tuhiwai Smith, Linda, Eve Tuck and Wayne K. Yang, eds., Indigenous and Decolonizing Studies in Education, Mapping the Long View, New York: Routledge, 2019.

Watts, Vanessa, “Indigenous place-thought & agency amongst humans and non-humans (First Woman and Sky Woman go on a European world tour!)” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society Vol. 2, No. 1, (2013), 20-34

Wilson, Shawn, Andrea V. Breen, and Lindsay DuPré, Research and Reconciliation: Unsettling Ways of Knowing through Indigenous Relationships, Toronto: Canadian Scholars, 2019.

Wilson, Shawn. Research Is Ceremony: Indigenous Research Methods. Black Point, NS: Fernwood Publishing, 2008.

Vizenor, Gerald, Fugitive Poses: Native American Indian scenes of absence and presence. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2000.

_____________, Survivance: Narratives of Native Presence, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2008.