Book Reviews: Icebergs, Zombies, and the Ultra Thin and Sick City

Two new Canadian-authored books address the idea that "form follows finance."

Icebergs, Zombies, and the Ultra Thin: Architecture and Capitalism in the Twenty-First Century

By Matthew Soules. Princeton Architectural Press, 2021

Sick City: Disease, Race, Inequality and Urban Land

By Patrick M. Condon, 2021

The axiom “form follows finance” is not new, but its effect on architecture and affordability is undeniably at a crisis point. Two new books on the subject, both by professors in the University of British Columbia’s School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture, aspire to unpack the effects of this phenomenon on the shape and operation of big cities. (Disclosure: I have collaborated on past editorial projects with both authors.)

Matthew Soules’ Icebergs, Zombies, and the Ultra Thin: Architecture and Capitalism in the Twenty-First Century explores the visibly tangible effects of a globalized economy. Its title references three of the most unsettling new architectural formats generated by the global commodification of real estate. And that’s just the hook: the bracing reality is that finance capitalism determines the shape of our built environment far more than any red-blooded architect would care to admit.

“Icebergs” are created by those who, having maxed out their allowable height and footprint, go deep underground—several storeys, in fact—to the point where the structure we see above ground level is just the quasi-literal tip of the proverbial iceberg. In London, England—where the super-wealthy are not content to be confined to expensive-but-narrow Victorian townhouses—ruthless, shrewd property owners take advantage of the fact that conventional building codes restrict height, but not depth.

“Icebergs” are created by those who, having maxed out their allowable height and footprint, go deep underground—several storeys, in fact—to the point where the structure we see above ground level is just the quasi-literal tip of the proverbial iceberg. In London, England—where the super-wealthy are not content to be confined to expensive-but-narrow Victorian townhouses—ruthless, shrewd property owners take advantage of the fact that conventional building codes restrict height, but not depth.

“Zombies” are houses and condo units left vacant by absentee speculators who buy them not to live in or rent out, but to hold, like gold ingots in Fort Knox. The term “ultra-thin” applies to those buildings whose height is proportionally much greater than their footprint, yielding a pencil-thin tower of penthouses. That’s the kind of residential unit that is, in moral terms, the least needed and yet the most profitable—hence its proliferation.

It’s useful to understand just why and how architecture mutated to create these products of architectural Darwinism. At this, Soules excels. He unpacks not just the market logistics that have led to these mutations, but also the broader political economy that drives them. The Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs) and Mortgage-Backed Securities that emerged in the 1980s have facilitated the commodification of shelter, allowing legions of middle-class and affluent investors to pool resources, feeding the corporate beast of mega-developments and mass holdings of rental buildings.

The new semiotics of wealth include such creations as Vancouver House, the twisting tower designed by Bjarke Ingels Group with DIALOG. The sales package for its individual luxury units included a promise to donate housing to needy Cambodians, like a medieval Pope’s swap of indulgences for church donations. But the architecture of Vancouver House won’t necessarily be used as housing, luxury or otherwise. “This top-heavy building transforms from a triangular plan at its base to a rectangular plan up top—a formal metamorphosis that increases the most expensive and profitable floor area at its apex,” observes Soules. “While enhancing profitability, the sculptural dynamism masks an absence of lived vitality. If its usage follows existing patterns, its upper units will be owned but will sit empty for much of the time, while the form itself minimizes the more modestly priced units that are most likely to be regularly inhabited. It is a dead space masquerading as dynamic—a kind of animated zombie.” Over eight chapters, the extent to which our capitalist society determines architectural form is clearly and concisely laid bare. “Like any discipline, architecture possesses internal logics and cultures that are unique to itself […] those internalities can be said to be autonomous,” writes Soules. But, he avers, “I believe they have no meaningful autonomy from the workings of capitalism.”

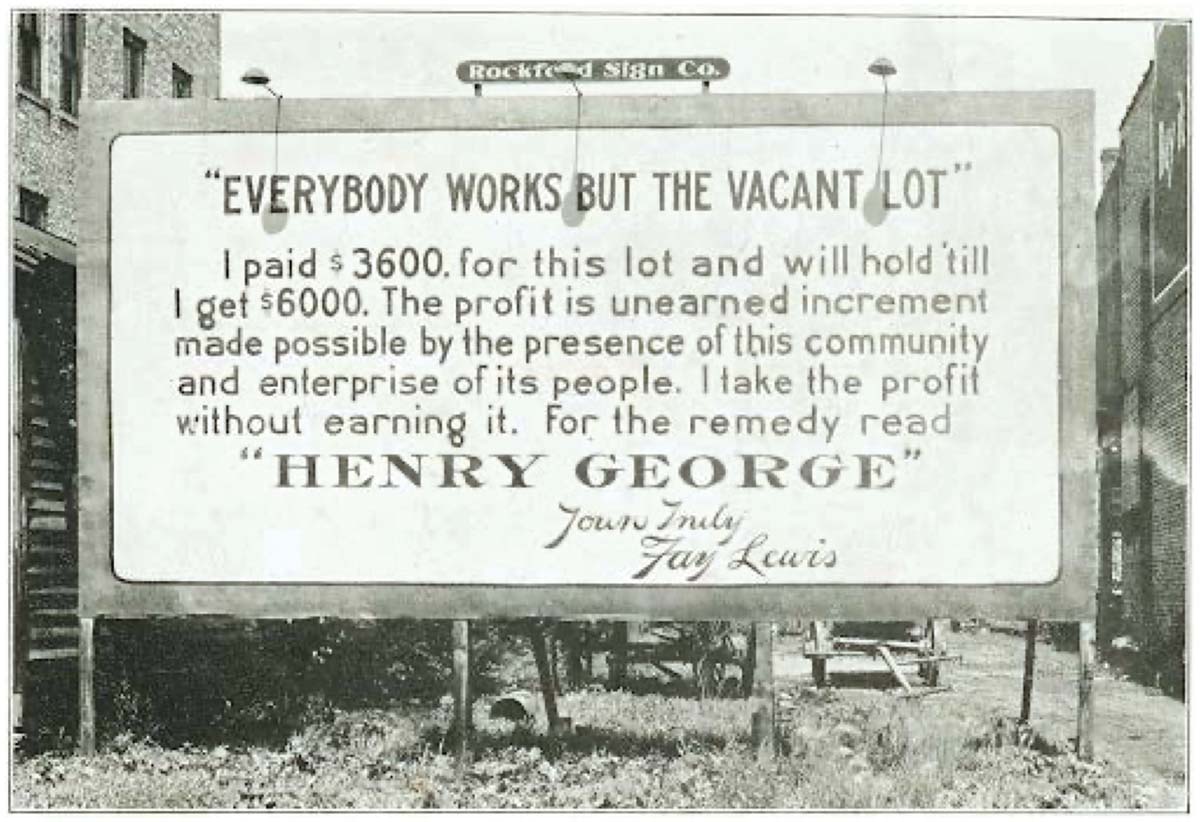

In much the same spirit, Patrick M. Condon observes with horror the current political economy and its effect on our communities. In Sick City: Disease, Race, Inequality and Urban Land, he delves well beyond architectural form to attack the political basis of land use and ownership. Where Soules has observed the architectural travesties as though circling the globe on a satellite, Condon gets down into the trenches, into the minutiae of zoning bylaws and municipal tax structures that exacerbate class disparity and undermine individual well-being.

In much the same spirit, Patrick M. Condon observes with horror the current political economy and its effect on our communities. In Sick City: Disease, Race, Inequality and Urban Land, he delves well beyond architectural form to attack the political basis of land use and ownership. Where Soules has observed the architectural travesties as though circling the globe on a satellite, Condon gets down into the trenches, into the minutiae of zoning bylaws and municipal tax structures that exacerbate class disparity and undermine individual well-being.

The book focuses on the United States, although, as Condon acknowledges in a preface to the Canadian edition, the same inequities he outlines plague our own metropolises, particularly Toronto and Vancouver.

Condon outlines the inherent problems created by “land Rent”—the formal economic valuation of land in both the short and long terms, which he capitalizes to distinguish it from the ordinary rent that people pay to live and work in a place. The instrumentalization of land Rent (for instance, through REITS) exacerbates inequality among races and social classes—in housing, healthcare, and community life. Conventional planning and zoning do little or nothing to help, and in many cases make matters worse through public policies that ultimately favour speculation over habitation.

Most trenchantly, Condon blows apart the speciously self-serving argument of the development industry—often mindlessly adopted by municipalities—that increasing the housing supply automatically increases affordability. That fallacy relies on an overtly simplistic reading of the law of supply and demand, as though houses are cranberries or other locally sold, non-essential products.

Condon plunges into the statistical complexities of global and local land-use economics in daunting detail, with varying degrees of clarity. In his preface, Condon notes that because of the urgency of the subject, he “resolved to write this book in months rather than years.” That haste is evident in the finished product. It’s hard to criticize a call for social and racial equality, especially since this author has served as an insightful, brave and sometimes-misunderstood critic

in the cacophony of commentary on this subject. But the very importance of his argument calls for a constructively honest critique—so here goes. This book would be far more effective and influential if—like a building or a city—it were structured and designed more carefully. It does not appear to have had the benefit of a substantive editor or graphic designer. The book’s serifed font is not reader-friendly, and the annotations of its charts, graphs and maps are reproduced at a size and resolution that makes them almost unreadable in places, and certainly less compelling than if reproduced at an appropriate scale and resolution.

These graphic shortcomings are not mere trifles. If part of an author’s claim to authority includes a grounding in design—urban, architectural, or other—it’s hard to captivate and convince a wider readership when the design of the book itself is mediocre.

A revamping of any further editions would be a great idea. In the meantime, Condon is generously offering the electronic version of this book for free and is selling the physical version at cost, he notes in the preface. We can hope that his most salient arguments can reach and compel some emerging scholars to further investigate the root causes of urban economic disparity, now and in the future.

Architectural curator and critic Adele Weder is a Contributing Editor to Canadian Architect.