Measures of Diversity

Workplace consultant Russell Pollard parses the results of a recent survey on diversity, equity and inclusion in Canadian architectural and engineering firms.

In January 2021, workplace people and culture consultancy Framework Leadership conducted a survey on workplace culture, leadership and inclusion within Canadian architecture and consulting engineering firms. The aim was to better understand where the industry stands in terms of diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI), and to consolidate the experiences of employees and jobseekers in these professions in both a quantitative and qualitative way. Over six hundred people responded to the survey, representing individuals at different stages of their careers, in different areas of the country and in different roles within their organizations.

Many employers have acted to support diversity in the industry.

An important finding was that the majority of employees—83%—believe that their employers are genuine in their commitment to diversity in the workforce. This commitment was backed up by several examples of employers investing in DEI-related training and education, supporting existing or new DEI committees and initiatives, and donating to organizations that support DEI in the broader profession. Some employers have begun to embed an equity lens into each stage of project work.

Support for diversity is important to prospective and current employees.

In what remains a competitive talent market in these professions, the work of DEI is also an important consideration for recruitment and retention. The survey asked respondents to identify their top factors for making employment decisions. “Quality of relationships with colleagues” and a “Supportive, inclusive workplace culture” were among the top answers selected—ranking third and fourth after salary and project opportunities.

An important consideration for inclusion in the workplace is psychological safety. This relates to individuals’ feelings of belonging, and whether or not they can learn, make mistakes, contribute, and challenge others without judgement or negative repercussions. Psychological safety is necessary when teams put forward new ideas, or when determining the best solution for a given mandate. There is also a relationship between psychological safety and employees’ intentions to remain with their employer. 11% of employed respondents indicated they are actively looking for new opportunities, 37% indicated they are open to new opportunities but not actively looking, and 52% indicated they are not actively looking at all. Respondents who indicated higher agreement levels with questions related to psychological safety were more likely to be intending to remain with their current employer. This further bolsters the business case for supporting DEI at work.

Results demonstrate that people who are members of different identity groups experience the workplace differently.

Decades of research have shown that women and men experience the workplace differently. The current survey reinforced that gender affects access to opportunities, mentorship and leadership roles. Women indicated lower agreement levels than men with the statement that read: “Members of leadership initiate conversations with me about my career development and advancement.”

To better understand how members of various other identity groups experience the workplace, an intersectional approach to the assessment was applied, looking at the overlaps between social identity and systems of power. The results showed that men who identify as LGBTQ2S+ have much lower than average agreement levels with the statement that members of leadership initiate career development conversations with them. Interestingly, men with caregiving responsibilities indicated the highest agreement levels with this statement—whereas women with caregiving responsibilities indicated lower-than-average agreement. Women with disabilities had the lowest agreement levels with this statement.

For organizations and employers that aim to support diversity and establish equity, an intersectional approach should be applied to ensure that differences in experiences and needs within identity groups are recognized.

Transparency is important to supporting diversity and equity.

Understanding that people experience workplace culture and leadership differently heightens the need to establish equity. Only 11% of respondents indicated that their employers’ processes for advancement are transparent. When these processes are not transparent or observable, and leaders do not initiate conversations on career development, it creates barriers to advancement. A well-communicated and clear process helps people take ownership of their career development in an organization, and can reduce the impact of leaders’ conscious and unconscious biases.

Apart from career advancement, salary is another area where a lack of transparency was identified. Salary is the top decision-making factor related to employment for 40% of respondents, and among the top five factors for 71% of respondents. Yet only 8% of respondents indicated that salary ranges were made public by their employer. Having established and communicated salary ranges for roles in an organization can reduce the perception (and reality) of pay inequities.

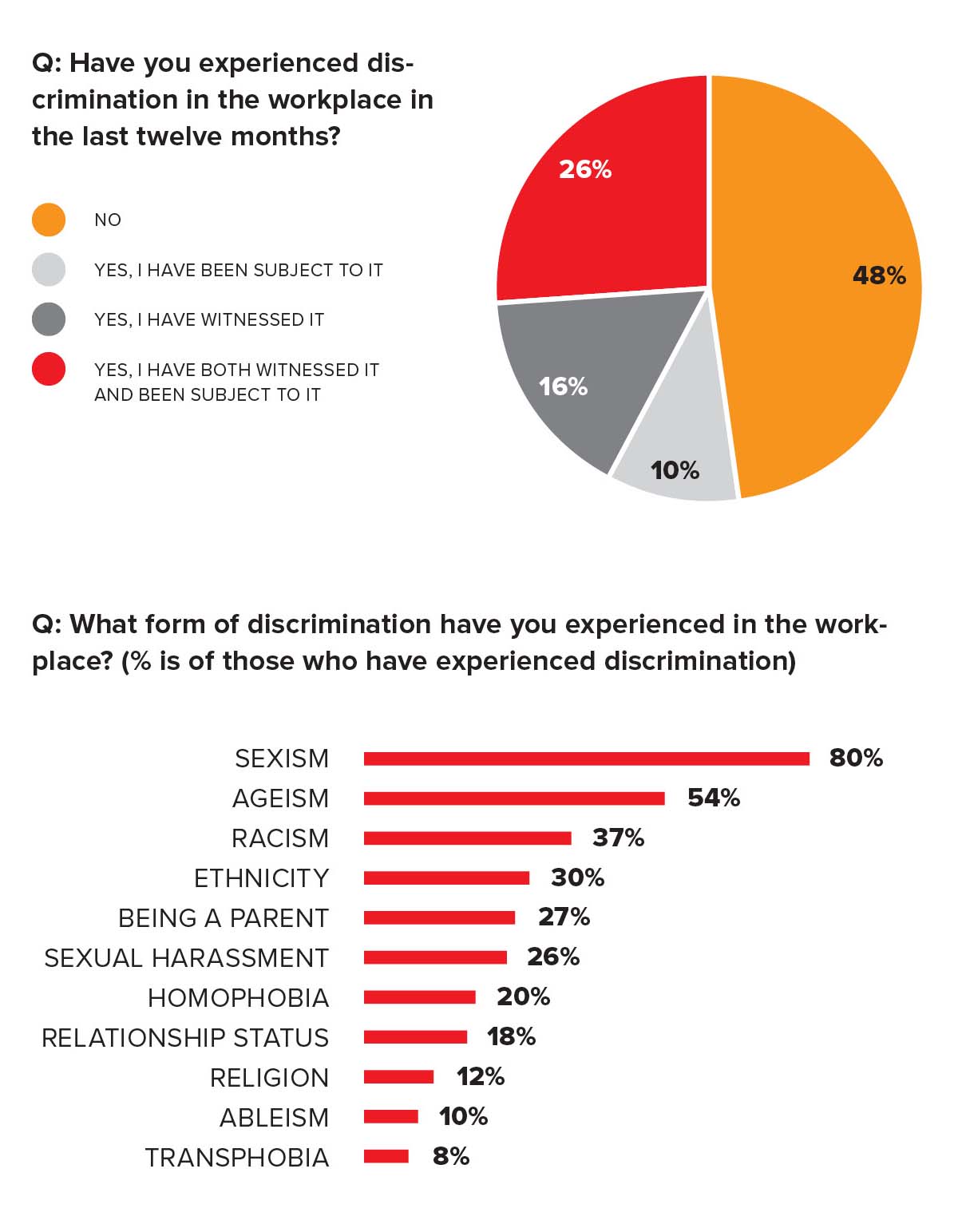

Half of respondents have recently experienced discrimination in the workplace.

Just over half of respondents (52%) indicated that they have witnessed or been subject to discrimination in the workplace in the past twelve months. 36% of employed respondents indicated that they were subjected to discrimination in their work. Sexism, ageism and racism were the most prevalent grounds for discrimination. On the positive side, people who expressed confidence that reporting discrimination would result in a fair outcome were less likely to experience discrimination. This speaks to the need for workplaces to have prominent and enforced codes of conduct, along with fair processes for dealing with any incidents.

Of course, architects and consulting engineers do not operate in silos. Survey responses indicated that discrimination comes from people external to the workplace—including clients, contractors and project consultants—as well as from colleagues and members of senior leadership. Individuals who aim to progress in their careers are expected to build strong relationships with clients, yet clients may discriminate against them based on gender, age, race or sexual orientation. This highlights the fact that this is an industry issue—not only a workplace one.

Jobseekers indicated discrimination in their search for employment.

In 2013, the Ontario Human Rights Commission outlined how employers and regulatory bodies must not discriminate against internationally trained immigrant professionals. However, this survey found that having “no Canadian experience” remained a key barrier to employment for these professionals. Many respondents—even those educated in Canada—indicated that they have changed their names on job applications to mitigate the impact of bias in the recruitment process.

Another potential barrier for AED jobseekers is a dependence on peer networks. Many jobs are not posted publicly, or people with connections are given preference. When asked where they first learned of their current role, 41% of employed respondents stated that it was “Through a personal or professional contact” and only 22% stated that it was “Through a public job posting.” This phenomenon has been identified in the AED sector in the United States and the United Kingdom as well. Although peer networks will likely always play a role in recruitment, relying solely on them limits the pool of candidates that firms attract. Flawed recruitment practices can also result in an underdeveloped employer brand.

Every individual and organization will have its own approach to necessary change.

For years, architecture firms—and indeed, most service sector businesses—have acknowledged that their employees are their greatest resource. The work of supporting diversity, equity and inclusion in the workplace is about ensuring that all persons have the resources, opportunities and relationships to contribute meaningfully and to grow. As the architecture profession actively seeks to become more diverse, employers will benefit from starting meaningful change early. Doing so will give them a competitive advantage in attracting the best of the current and future members of the architectural workforce.

This work cannot be done by employers alone, however. Many of these issues reflect the culture of the industry and broader, systemic barriers. For several years, DEI efforts have been led by organizations like Building Equality in Architecture (BEA), the Black Architects and Interior Designers Association (BAIDA), and the 30×30 Women in Engineering initiative by Engineers Canada. These are incredible organizations, communities and initiatives to support and connect with, and they deserve much of the credit for the progress the industry has seen over the years.

Supporting diversity and inclusion ultimately requires individuals—regardless of their formal leadership position or personal authority—to develop their own knowledge, skills and awareness. The goal is its own reward: building respectful, genuine relationships with colleagues and clients alike, and contributing to improving the industry.

Russell Pollard is a consultant on workplace culture, leadership and inclusion for professional services firms and is active as a volunteer and guest speaker in the construction industry. He can be reached at [email protected].