Fiction All the Way Down: Impostor Cities, Venice Biennale

Impostor Cities, Canada’s pavilion at the 2021 Venice Biennale Architettura, exists as much on screen as on the ground. It’s a form of presentation that suits its subject: how Canadian cities stand in for other places onscreen.

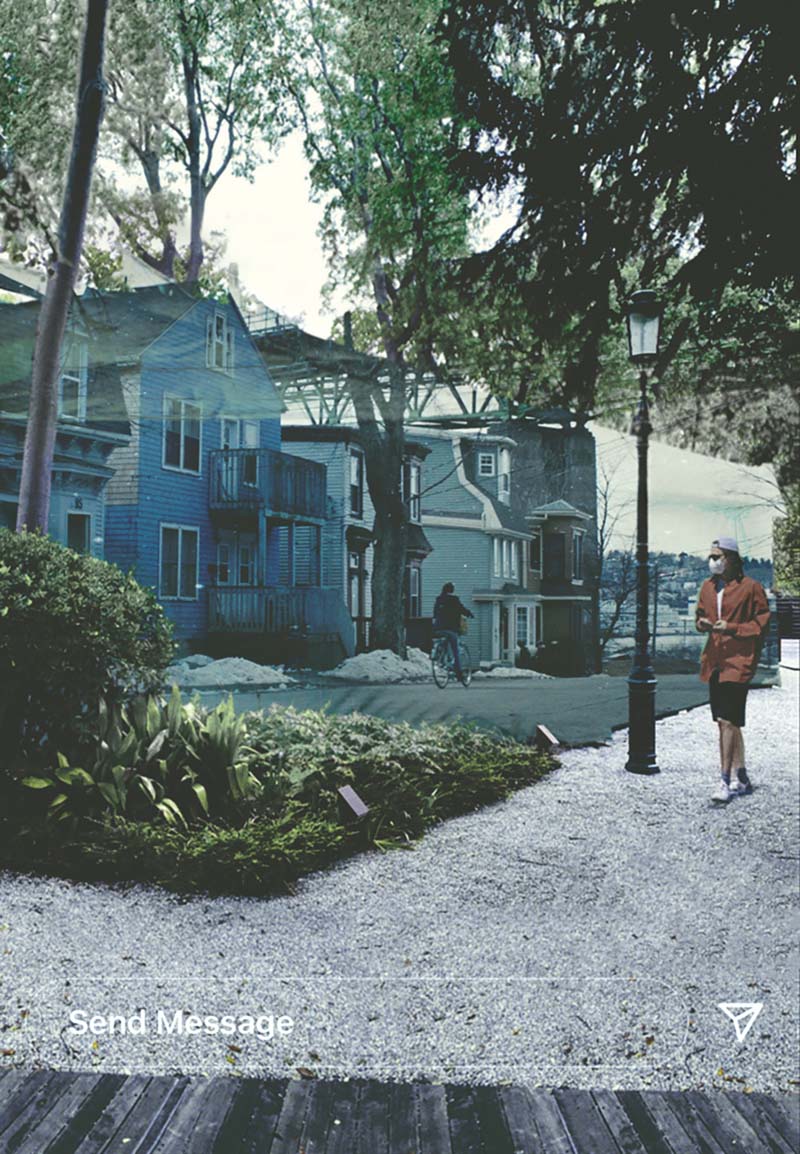

Impostor Cities, Canada’s pavilion at the 2021 Venice Biennale Architettura, exists (as do a number of other pavilions this year) as much on screen as on the ground. Its interior shuttered, the physical pavilion can only be enjoyed from outside, mediated through augmented reality (AR). A more complete presentation of its content resides online at impostorcities.com. It’s a form of presentation that suits its subject: how Canadian cities stand in for other places onscreen.

Canadian cities that “imposture” in this way are taking part in what has been called the “Frankenstein space” of cinema. In one of the video interviews flitting around the Impostor Cities website, production designer Paul Austerberry describes one such space he created for The Shape of Water. The story’s Orpheum Theatre is named for a historic Baltimore venue, and cobbled together from the exterior of Toronto’s Massey Hall, a temporary cinema marquee, the interior of the Elgin Theatre, and another interior constructed on a sound stage. Every two years, Venice itself might be seen as a Frankenstein space too, as installations representing architectural cultures from around the world coalesce to form the Biennale.

The theme of the Biennale this year is “How Will We Live Together?” Impostor Cities references that question in its own terms: “The world we live in together is the global generic city we experience together onscreen,” says co-curator David Theodore. It’s a provocative statement, and one that matters for architecture. As actor and filmmaker Sook Yin Lee points out in her own interview on the website: “Architects like to think that buildings are highly specific to their site and use. Not true!” Ouch. We have to admit our job often involves assembling off-the-shelf components, following universal codes and standards. Are we really creating generic, fake spaces that could just as well be somewhere else? Artist and writer Douglas Coupland offers one answer: “In Canada, you could almost say that the measure of success of any piece of architecture is how badly movies want to make it look like the States. It’s pretty much that simple, I think.”

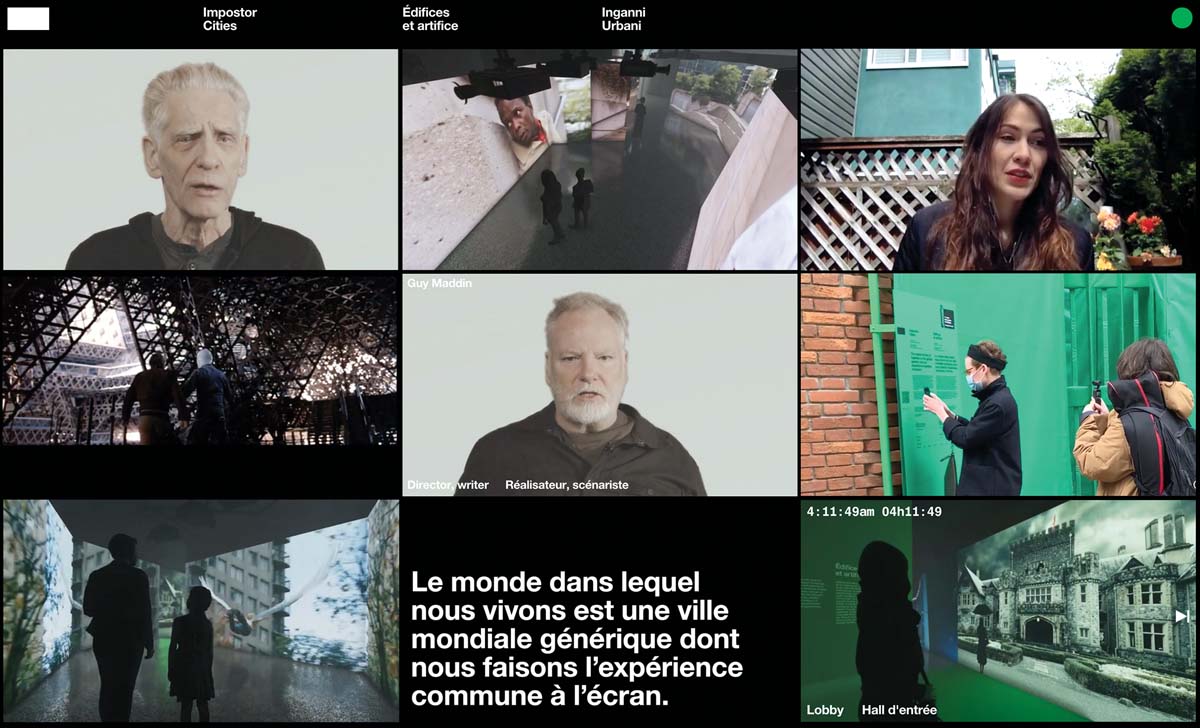

Or maybe not. As we explore impostorcities.com, we thankfully encounter a number of other “takes” on the relationship between film and architecture. The site includes dozens of interviews with prominent filmmakers from across the country—writers, directors, producers, location scouts, art directors, and production designers. The voices of this chorus are interspersed with film and television clips shot in Canada, as it stands in for other places. As we click through, the scenes disappear and reappear, at times aligning so that we see, for example, Simon Fraser University or Roy Thompson Hall as it appears in four different films. Other sequences show us a Venice visitor using the AR app to watch film clips “on” the outside of the pavilion’s green-screen shroud, designed by co-curators Thomas Balaban and Jennifer Thorogood of T B A. Yet others take us virtually inside the closed pavilion; on its facsimile walls, we can see “projected” film excerpts. If fundraising is successful (the site includes a merch page to this end), the scaffolding and green screen may go on a cross-Canada tour—a kind of mobile impostor of the Venice pavilion. That would also be an opportunity to see several supercuts of film sequences which will never be seen in public otherwise.

For now, all we have is the array of shifting images that fill the website’s nine-square grid (which happens to be the pattern underlying several historical and mythical cities). Inspired sound design by Randolph Jordan and Florian Grond overlays audio from the films and ambient sound from key real-world architectural sites. Rather than cut from its surroundings like the moving images, the audio creates a context: disrupting, connecting, and punctuating the film clips, not unlike the role sound plays in film. The website’s matrix becomes a non-linear, recombinant labyrinth of ever-changing images and sounds. (As a result of all these shenanigans, the site consumes a huge amount of bandwidth, so watch at your own risk if your adult child is playing Path of Exile 2 on the same internet connection.)

It all seems designed to stop us just short of reaching a conclusion. What is an “impostor,” really? Quebecois film-maker Luc Bourdon points out, poignantly, the weakness inherent in this role: “How can we have a strong identity when we are always looking at the identity of another as our own?” Director David Cronenberg, on the other hand, speaks proudly of Toronto’s ability to “imposture itself”—posing as not just another city, but as other versions of Toronto. X-Men Art Director Tamara Deverall tells us how Toronto’s laneways, playing the role of the back streets of New York, have distorted the way the world sees Manhattan—which is not, in fact, a city of alleys. Indeed, filmmaker and writer Marcel Jean describes film as “un très beau mensonge”—“a very beautiful lie.” Perhaps a lie that tells the truth? Elle-Máijá Tailfeathers (director of The Body Remembers When the World Broke Open) observes that many young filmmakers today—she makes the case that they tend to be women—present spaces that are in no way generic, or clean, or geared toward a market.

At first glance, the exhibition seems to prioritize filming locations in Toronto, Vancouver or Montreal. But significant, if smaller, film industries elsewhere also make an appearance, making use of equally significant architectural and landscape heritages. One representative from these small centres is Guy Maddin, who, it has to be said, has never made a film in which Winnipeg stood in for anything other than, as Maddin puts it, a “mythologized” version of itself. (At times, I had to feel sorry for cities like Vancouver for the paucity of films in which they get to play themselves.) Echoing Marcel Jean, Maddin points out that the curation of the lies you tell about yourself is more revealing than any confession would be.

These contradictory takes on imposture and authenticity suggest a common ground between film and architecture. As project co-curator David Theodore has put it: “One of the powers of architecture is its power as fiction. It’s not like the architecture that we live in doesn’t also participate in storytelling and making imaginative worlds. It does. You’re using a fictional world to talk about another fictional story. That’s where it really gets interesting. It’s about imagining what the imagination can imagine. It’s fiction all the way down.”

If architecture, like the X-Men (a favourite of the exhibition) has “powers,” Impostor Cities exhibits an underlying respect for them. Evan Webber, art director of The Handmaid’s Tale, underlines this in his interview: “The greatest architecture has the greatest power to mutate and to reinforce its idea on you, without you really being that aware of it.” So filmmakers come under the thrall of architecture, even as they play with it. Webber actually studied architecture, at Waterloo, before starting his career at KPMB, on the Governor General’s award-winning Kitchener City Hall. He maintained his licence until recently, and in an interview for this review, underlined what film and architecture share: “They both take enormous and arduous planning and require immense efforts toward collaboration. Conjuring their final result is always an enormous leap of faith as well as a huge personal expenditure of one’s creative energy.” And Austerberry, who won an Academy Award for his production design of The Shape of Water, credits his architectural training at Carleton for encouraging him “to think outside the norms of what architecture was … [it] certainly helps with what I do now in film design.”

In the end, Impostor Cities refuses to answer the question of how we will live together. Who could? Its strength is in its openness to diverse interpretations. Unlike many pavilions, this one does not give us an ideology. Instead, it presents an emergent phenomenon, and encourages us to be intrigued—not just as we view these shifting images, but as we move into the future. It’s a conversation, and a way of conversing, appropriate to a Frankenstein space. And a tribute to the intelligence, inventiveness, and rhetorical skill of the curatorial and design team.

Lawrence Bird (MRAIC) is an architect, urban designer and visual artist. He works in Winnipeg at Sputnik Architecture Inc.