2021 RAIC Gold Medal: Architecture of Insistence—Crafting Place, Building Material Legacies

Cultural theorist Elke Krasny analyzes the ways in which Shim-Sutcliffe has achieved an oeuvre, through the context of today’s globalized economic and cultural conditions.

visual effects looking outwards. Several significant black locust trees are part of the Carolinian forest where the project is situated. Photo by Scott Norsworthy

Since they first began their collaborative practice, Brigitte Shim and Howard Sutcliffe have continuously dedicated their life in architecture to building an architectural oeuvre. Situated in the decades of globalization following the 1980s, this oeuvre—which is primarily located in Canada, but also in other geographical and climatic environments including Hong Kong, Hawaii, and Russia—can be understood as a single body of work, which has been insistently and purposefully created over time. Each one of their buildings adds significance, depth, nuance, and meaning to this body of work. In turn, the body of work in its entirety adds significance, depth, nuance, and meaning to what will in the future become understood as the present-day contribution to the making of architectural history.

Shim and Sutcliffe are keenly aware that architecture is situated in specific geographical locations and environments, and exists only through the creation of material manifestations. Over time, these material manifestations can become material legacies: articulations of their culture, place and time. Throughout their work, Shim and Sutcliffe have actively avoided the misfortunes of iconicity, placelessness, conspicuous construction, and hedonistic consumption that befell much of contemporary architecture in the decades of rampant globalization and neoliberal capitalism that followed the 1980s.

German-Jewish philosopher and cultural critic Walter Benjamin noted that the historical materialist must include the notion of the present when thinking about history, which, of course, always extends to the history of the present moment. His insight leads me to propose that Shim-Sutcliffe’s body of work is a manifestation of an architecture of insistence, when read against the devastating (and even disastrous) effects of globalization and neoliberal capitalism on the production of architecture today.

The ways in which Shim-Sutcliffe has achieved an oeuvre—a whole body of work, in which each of their buildings contributes to creating more meaning than their mere sum total—has to be analyzed through the context of today’s globalized economic and cultural conditions. As American architect and architectural historian Peggy Deamer has lucidly observed, the history of architecture is the history of capital. Therefore, the history of today’s architecture has to be understood as the history of globalized capital.

Following the 1980s, contemporary architecture was swept up in the image-centric and placeless culture of globalization. Supported by the advent of digital production, this unleashed not only a plethora of new shapes and forms, but also new functions that came to define the architecture of our historical moment: iconicity, spectacle and financial speculation.

The anywhere-can-be-everywhere mindset of globalization led to a new mentality of placelessness, which became firmly entrenched in architecture—even though it was previously well-understood that architecture cannot exist or survive outside of the conditions of its physical site and its geographical environment. The place-based understanding of architecture gave way to an image-based understanding, with architecture primarily serving the function of providing iconic images, which are needed to advertise, market, and sell experiences. Such images suggest that architecture can easily be placed anywhere. Consequently, the notion of architecture-as-image transformed the very notion of place, in such a way that anywhere was believed to be everywhere, and everywhere was believed to be anywhere.

This prevailing idea of architecture-as-image gave rise to the production of iconicity-on-demand, with buildings becoming spectacles for hedonistic consumption. Spectacular iconic buildings around the globe are evidence of this architectural trend connected to globalized capital.

At the same time, globalized capital began to harness the power of architecture—and in particular, the power of towers—as instruments of financialization. Super-tall buildings, including condominium towers as well as of office towers, are the expression of this new function of architecture. Iconic architectural objects built for the purpose of spectacle and units of architecture built for the purpose of financial speculation—with the singular goal of maximizing return on financial investment—are, in fact, hostile to the prime function and core value of architecture, which is to create places for living.

Spectacle and speculation, which have come to largely define architecture at our historical moment, share the same Latin root, spec, which means “to look” or “to see.” With iconic architectural objects trending online, and even canonic examples of historical architecture first and foremost consumed as Instagram images, placelessness has become a profound cultural experience of our time.

Such placenessness—with buildings understood to be images that are delocalized, singularized, and isolated from their place—has impacted our understanding of the effects of architecture on place, as well as the importance of understanding place in creating architecture. The centrality of the gaze that unites spectacle and speculation sees architecture as image: useful because of its potential for conspicuous construction, marketable experiences, hedonistic consumption, and financial speculation. This way of seeing has profoundly eroded the understanding of place, and what architecture does in, with, and to a place. It erases the fact that place is the ground—materially and semantically—for architecture’s very existence.

Crafting place, which is at the core of Shim-Sutcliffe’s body of work, counteracts the image-over-place mentality at the heart of the twin regimes of spectacle and of speculation. Crafting place starts with considering given sites in geographical and climatic terms, but also in cultural terms. Crafting place results from the most intimate interweaving of site and building, which is in stark opposition to the anywhere-is-everywhere mindset of globalized architectural production.

The body of work created by Shim-Sutcliffe can be understood as an architecture of insistence as they pursue their site-specific approach to crafting place, refusing to compromise architecture to image, nor site to sight. Kenneth Frampton’s 1983 essay Towards a Critical Regionalism: Six Points for an Architecture of Resistance was a reminder that architecture can, and should, resist the homogeneity of modern society. Rather than an approach based on resistance, I propose that Shim-Sutcliffe’s achievement of an uncompromising body of work sets a precedent for an architecture of insistence.

Resistance, in my mind, speaks to a political philosophy connected to anti-fascist and anti-capitalist struggles and social movements. Insistence, on the other hand, speaks to the dedication to, and ethics of, carving out conditions for making architecture uncompromisingly committed to its core values.

An architecture of insistence works within the economic realities of capital, yet never gives in to spectacle and speculation. The degree of architectural perfection which has come to define Shim-Sutcliffe’s body of work—and is impeccably achieved in each one of their buildings—is, of course, highly labour-, resource-, and cost-intensive. Shim-Sutcliffe’s architecture of insistence is characterized by the ethics of putting to best use the resources that they are entrusted with by their clients, in order to create lasting material legacies. Firm in its course, such an architecture of insistence continuously affirms its core values in formal, aesthetic and material terms.

Buildings by Shim-Sutcliffe are built manifestations that architecture cannot be anywhere (or everywhere), but that architecture is always located on a specific site with given conditions. Crafting place means that architecture starts from the specificity of a location on the map, from the ground of any given site. This means to start from an ethics of responsiveness, which acknowledges that buildings cannot be severed from their site, and understands that buildings have social, environmental, and cultural impacts and meanings beyond the immediate scale of their footprint on the ground.

In Shim-Sutcliffe’s body of work, site-specific ecologies matter. These include conditions of climate, weather and light, urban and natural landscapes, cultural forms and shapes, local approaches to construction, the skills of builders and craftspeople, and traditional uses of materials. Their attentive responsiveness to such conditions has led Shim and Sutcliffe to create unique responses to each of their buildings’ sites. Their architecture is always inseparable from its place, and gives expression to environmental, social, cultural, and emotional belonging through its material composition.

Crafting place is a process that unfolds over time. The site on which a building is located existed long before the arrival of the building. Crafting place takes into account that buildings become part of a process of place, as it unfolds over time. To use American science studies and multispecies thinker Donna Haraway’s term, site and building are understood as sympoiesis, which means “making with each other.” The processes of crafting place, site and building are inseparable in their interrelatedness and interdependence. To craft a place over time, it is fundamental to never separate site from building, or material from meaning.

Crafting presents a form of knowledge-cultivation through architecture. Craft is commonly understood as knowledge that is passed along, gradually changing and adapting over time. Shim-Sutcliffe’s profound interest in the material legacies created by architecture has led them to closely study such knowledge-cultivation. They carefully examine the solutions provided by the historical modernist project and by vernacular architecture. They are particularly interested in understanding how buildings respond to the specific natural, climatic, cultural, and historical conditions that shape their sites. This in-depth study retraces and uncovers how particular buildings respond to the site-specific ecologies of different geographies and environments.

In their own nuanced architectural responses to sites, Shim and Sutcliffe have drawn on these material legacies. Crafting, here, is understood as the knowledge-cultivation of site-responsiveness—a core insight to be gleaned from architecture that cannot be reduced to its image.

Crafting place is a knowledge-cultivation that pushes back against the dictatorship of architecture-as-image by making room—and time—for the experiences of material intimacy, the sense of touch and visceral feelings of tactility, and an attentive listening to material and spatial compositions. It makes space for the contemplation of the (im)materiality of light, as light moves through buildings and sites, and views, as inhabitants move around in the buildings.

Crafting place is not reducible to the time it takes to look at an image. Rather, crafting place unfolds over time. Shim-Sutcliffe’s buildings provide for experiential richness. Their buildings enable those who live in them, and with them, to grow their sensorial attentiveness, and their nuance in making meaning from spatial and material encounters. Crafting place allows for the unfolding of the meaning of buildings over time. The buildings created by Shim and Sutcliffe invite an embodied, affective, and even spiritual experience of everyday living as a sympoietic process between humans, buildings, and sites.

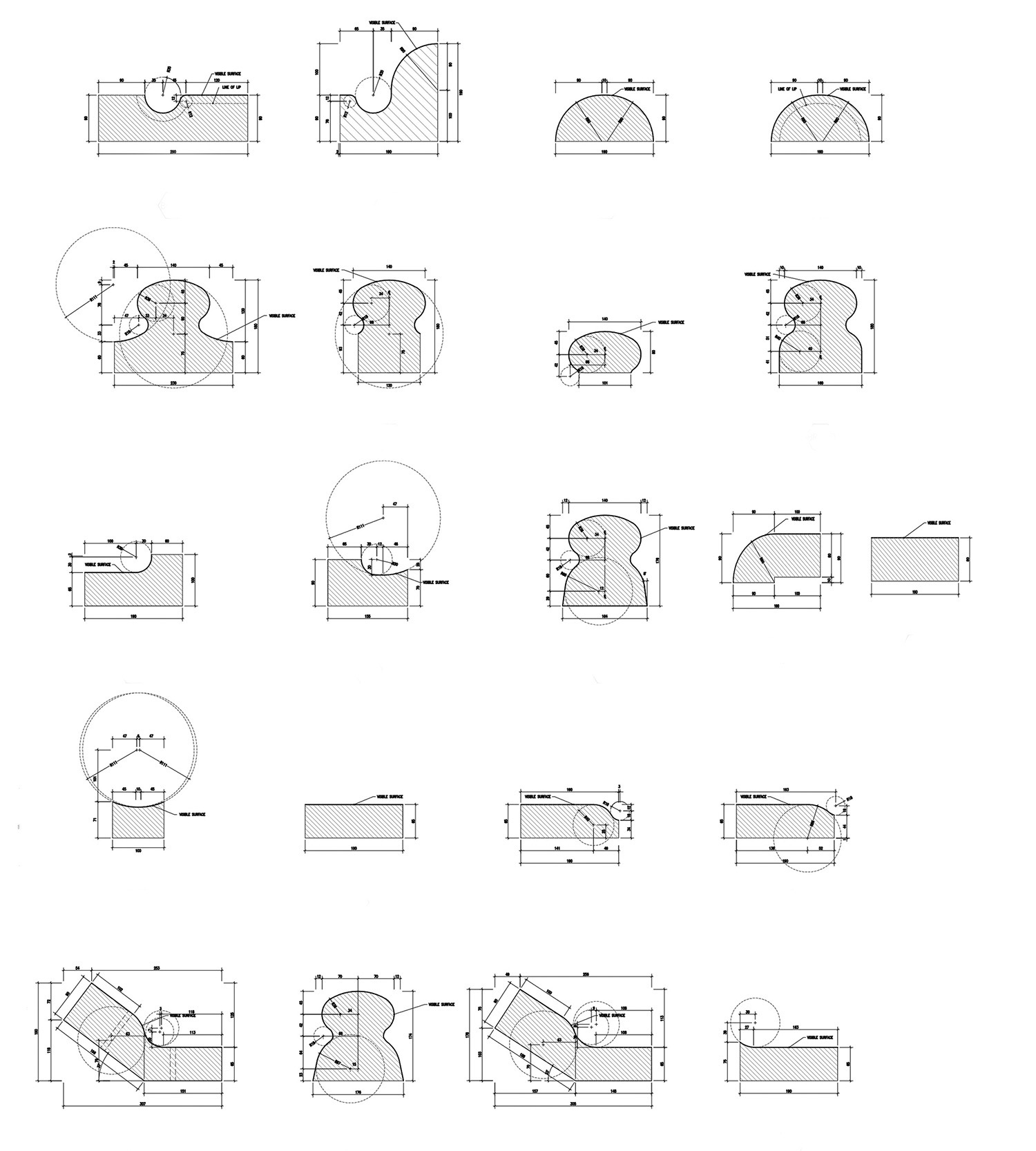

Drawing architecture into existence—as Shim-Sutcliffe do with dedication, insistence, and continuity—is a process that requires time. Time is needed to create specific responses to the complex entanglements that sites present. Drawing into existence can literally refer to the practice of materializing architectural ideas with paper and pencil. Central to Shim-Sutcliffe’s creative practice is making time for such drawing, as well as for testing models at all scales, from view models to full-scale mock-ups. Their craft harnesses the flawless precision of digital fabrication, but also allow for the small imperfections that are part of how materials are experienced, and that give them affective and emotional dimension. On a metaphorical level, drawing into existence refers to the process of bringing about and causing to exist—the larger idea of an architecture of insistence which causes architecture to be. As Shim and Sutcliffe connect site, material and spatial composition, they draw architecture into existence in both senses. Each of their buildings manifests a unique response to its site, be it a high-density urban context or a sparsely populated natural environment.

Shim-Sutcliffe’s work embraces all scales—from the design of doorknobs, built-in fittings, lamps and chairs, to small private homes and cottages, to larger-scale religious and residential buildings. Throughout, qualities like spatial generosity, calm serenity, choreography of nuanced experience, and intimate tactility are achieved by not separating vernacular traditions from modernist traditions, craft from art. The work unlocks and shapes the inherent qualities of materials, which includes respecting their processes of aging and weathering, as well as honouring the small imperfections that bring out the aliveness of materials. Shim-Sutcliffe’s architecture intricately weaves together the interior and the exterior, function and beauty, material and meaning, to appeal to the human senses. Building material legacies makes these ethical and aesthetical expressions of their time and their place.

Shim-Sutcliffe’s architecture of insistence is firmly rooted in a triple commitment: to be responsive to both nature and culture as it comes to specifically define each of their sites and their material choices; to be responsive to the needs and wishes of their clients; and to be responsive to the legacies of the modernist architectural project and vernacular building traditions. As Brigitte Shim and Howard Sutcliffe continue to cultivate and to grow their body of work, they remain carefully aware that crafting place not only requires time, labour and resources—but above all, an unwavering ethics of insistence. Staying true to their values, they use the core means of architecture—spatial and material composition—to create buildings that provide material evidence for these values and create material legacies. Crafting place draws into existence the built manifestations of architecture as a continuum of site, material, and building. Building is understood both as a noun and a verb: their work unfolds buildings’ potentials over time, in sympoiesis not only with their sites, but with all those who are touched by them and find their senses of belonging in them.

Elke Krasny is a curator, cultural theorist and writer. She is a Professor at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna, and heads its Department of Education. Her scholarship, academic writings, curatorial work and international lectures address questions of care at the present historical conjuncture, with a focus on emancipatory and transformative practices in art, curating, architecture and urbanism.

In 2012, Elke Krasny was a Visiting Scholar at the Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA). Her residence focused on studying the work of Brigitte Shim and Howard Sutcliffe in the CCA’s archives. Her CCA Visiting Scholar Seminar Shim-Sutcliffe: Crafting Architecture posed many questions about Canadian architecture and positioned the work of Brigitte Shim and Howard Sutcliffe within our current cultural condition. Her research-based curatorial work on global and Canadian architectural practices was presented in the exhibitions The Force is in the Mind: The Making of Architecture and Thinking Aloud | Making Architecture at the Architecture Centre in Vienna in 2008, at UQAM’s Centre de design in Montreal in 2010 and at the Dalhousie University School of Architecture in 2011. Through filmed interviews, photos, drawings, models and unusual objects, the exhibitions focused on the making of architecture, rather than on finished work.