State of the Nation: Alberta

Alberta Alberta’s economy follows a boom-and-bust cycle, tracking energy prices. The crash of the oil market has been devastating for the private sector as well as the province’s coffers—and this has hit architecture firms in turn. “Calgary has been decimated in the last four years,” says Linus Murphy of S2 Architecture. “I think it’s going to get worse before it gets better.”

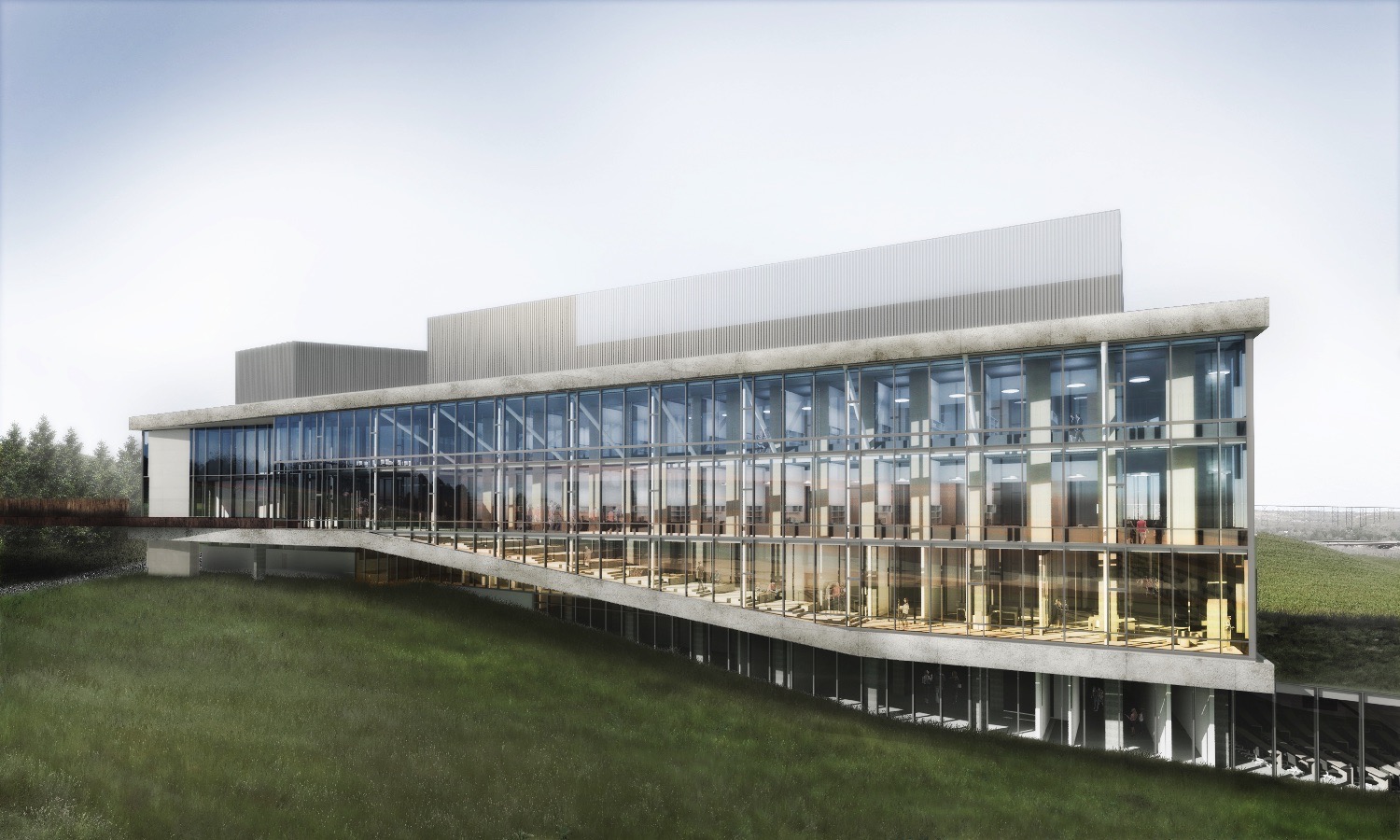

In the private sector, Calgary currently has a 27% office vacancy rate—higher than it was during the recession of the 1980s. Fees have been driven down by firms competing for the remaining work. In the public sector, the province has continued with deficit spending, but in an erratic manner. Some major public projects that started before the downturn have been completed, such as the University of Lethbridge’s $220-million expansion, by KPMB and Stantec Architecture, but others have been holding at the tender stage until funding becomes available. One major project, the $590-million Alberta Health Services super lab in Edmonton, was under construction, but the work was abruptly suspended after the government changeover in April. Other projects seem to be stuck at the study phase.

Several very large-scale projects have been pushing through—the $1.4-billion Calgary Cancer Centre (by Stantec in collaboration with DIALOG), for instance, and the $500-million BMO conference centre expansion (by Stantec, S2 Architecture, and Populous). But, according to Murphy, there has been a notable disappearance of mid-sized projects. As a result, a few firms lucky enough to land the mega-projects have prospered, while others have not.

The mood is somewhat more positive in Edmonton. Cynthia Dovell of AVID Architecture says that there has been a steady supply of small projects, which have allowed her to build up from a solo practice to a five-person firm over the past few years. “Edmonton could support many more small firms,” she says. Vivian Manasc’s firm, Manasc Isaac, has also grown over the past few years, working mostly in Alberta and in the North.

The organizational structures created by Alberta architects offer positive lessons for the rest of Canada. It’s one of only two provinces (along with Quebec) which splits the regulation of architecture and advocacy for the business interests of architects into separate mandates. The advocacy body, the Consulting Architects of Alberta (CAA), is made up of 38 member firms who represent 80% of Alberta architects.

The CAA has been at the forefront of negotiating for fairer contracts and procurement methods. It has been working with government and major institutions to adjust standard contracts, so that architects aren’t being asked to assume undue liability or give up copyright, for instance. Recently, it worked with Alberta Infrastructure to release two pilot qualifications-based selection projects. The City of Calgary has also been using qualifications-based selection. “They’re on their third RFP with this model, and we’re quite optimistic about the opportunity for credentials and experience to drive team selections—not low fees,” says Léo Lejeune of Stantec’s Calgary office. “This should result in better and better design in our community.”

The flagship of design-first procurement in Alberta is the City of Edmonton. Under City Architect Carol Belanger, Edmonton has developed a QBS-based system that pegs payment to the CAA fee schedule, taking fees out of the equation for selection. The city also maintains a standing offer list of emerging firms for smaller city projects, and held an open, anonymous design competition for a series of park pavilions.

Another Alberta innovation worth watching is Athabasca University. The institution started as a traditional campus-based university in 1970, but then pivoted to offering distance education courses, and now is at the forefront of online learning. Its purview includes architecture: for the past few years, it’s provided the academic courses for the RAIC Syllabus program. While the RAIC offers face-to-face studios for Syllabus students in major cities across Canada, Athabasca provides virtual design studios as part of its Bachelor of Science in Architecture. Although the idea of virtual studio courses rankles many professionals, Cynthia Dovell, who teaches in the online program, says that it is one way of encouraging people from a greater diversity of economic backgrounds to enter the profession. “Students in the Athabasca program often have financial challenges in going to a traditional school, because they need to work at the same time, and can’t move cities,” she says. With the almost complete replacement of drafting boards with laptops at offices and architecture schools, it’s increasingly plausible that online learning will be important in the future of design education.

On the sustainability front, Alberta never adopted the 2015 National Energy Code for Buildings, but recently leapfrogged to adopt the 2017 version, making it the first province to do so. When Alberta had a carbon tax, there were budgets allocated to photovoltaics on buildings as well, notes Vivian Manasc, although she adds, “now that our carbon tax has been repealed, it will be interesting to see whether these strategies will still work.”

There are other bright spots. There seems to be plenty of work in rural Alberta, in the form of a patchwork of small projects. And although Alberta has a younger population compared to other provinces, the private sector is looking to bring progressive care and seniors’ facilities to market. The City of Calgary has supported the development of creative mixed-use facilities—for instance, combining a fire hall station or local library with affordable housing—pushing the envelope on pairing different typologies. Edmonton’s recent Missing Middle competition solicited design-led proposals for developing affordable housing on five city-owned lots.

Dustin Couzens of Calgary-based Modern Office for Design + Architecture compares Calgary to Detroit: the economic downturn, he says, has forced individuals who were laid off to reinvent themselves and their industries. For instance, robotics technology startup ATTAbotics, founded by unemployed engineers, has quickly scaled up to a 200-person company. Modern Office completed an interior retrofit for the company, and now they’ve been commissioned to design a new standalone building. “Calgary on the whole has a conservative outlook on architecture,” says Couzens. “Thankfully, we’re finding individuals who are interested in looking for solutions that are out of the box.”

The slowdown has also led some architects to reinvent themselves. Shafraaz Kaba, formerly a partner at Manasc Isaac, recently founded a design consultancy called ASK for a Better World, which trains designers, constructors and clients on net-zero energy building techniques and processes. “Cities like Edmonton are making bold climate plans, but it takes all hands on deck to get people to a space where they can think that net-zero energy or zero-carbon buildings are possible,” he says. “I hope I can help energize our industry about how architects can make a difference in our built environment.”

Adds Ben Klumper of Modern Office, “An economic slowdown affords an opportunity to take stock and appreciate what good design can do in city-building. I hope we can come out of this with an attitude of going beyond asking ‘what’s the fastest and cheapest way to build?’, and instead asking ‘what’s the best way to do this?’”

This article is part of our State of the Nation series covering Canadian architecture region by region.