Carving Out a Path to Access

In 2018, Erin Shilliday received an unexpected email that would forever change how he approached his architectural work. It was an invitation to a Rick Hansen Foundation (RHF) Accessibility Leadership Forum event, described not as a typical meet-and-greet but as a working session with 50 influential voices in the disability community. It sounded intriguing for Erin, an architect based in Calgary, Alberta, but he wasn’t sure how he fit in.

He arrived at the session to find the small, intimate gathering – nothing like today’s version, an annual Accessibility Professional Network (APN) conference that draws people in by the hundreds. About half the participants at that working session had some form of physical disability. The gathering felt different, Erin remembered. “It was almost like Woodstock for disability,” he said. It was because people with disabilities weren’t a minority but a decisive majority. This was Erin’s first dive into accessibility, a subject he assumed he understood. Until he realized just how much he didn’t.

“We broke into groups and spent hours hashing out ideas around accessibility,” Erin said. “You could tell that this was something personal for many people in the room. For me, it was the beginning of a deeper education.”

However, the moment that stuck for him was meeting Nabeel Ramji, a commercial real estate asset manager who used a power wheelchair. Nabeel asked Erin: “Why do you design buildings that don’t work for me?”

Erin was stunned, not by the question’s sharpness but by its simplicity. “He wasn’t being rude. But the question hit me hard. As an architect, I thought I was doing things right – following building codes and meeting regulations. But in that moment, I realized I wasn’t really answering the needs of people like Nabeel.”

A Realization Through Friendship

What started as a professional relationship between Nabeel and Erin quickly evolved into a friendship. They spent hours discussing the issues that people with disabilities face daily – things that Erin, as somebody without a disability – had never even considered.

Nabeel, who was born in Pakistan and adopted by a Canadian family as an infant, was diagnosed with cerebral palsy at nine months. His father, a doctor, had been told by the adoption agency that they could “send him back.” His father’s response was: “We love this boy. We’ll be just fine.” That love and acceptance stayed with Nabeel, but it didn’t shield him from the fact that the world is inundated with attitudinal and physical barriers. Despite excelling in school academically and socially – he received a standing ovation from his high school peers when he crossed the stage at graduation –Nabeel said it was difficult not to feel like an outsider in a world not built for him.

“I spent the first eight years of my life unable to speak,” Nabeel said, “so I know what it feels like not to have a voice. It’s isolating.” That experience made him acutely aware of barriers that many, even well-intentioned people like Erin, often overlook.

Erin admits that before meeting Nabeel, he wasn’t aware of anybody in his circle with a disability. The lessons he learns from their friendship have been incredibly humbling. “You think you understand disability because you follow the codes, but then you spend time with someone like Nabeel, and you learn how those codes don’t even scratch the surface.”

Erin, who had once followed building codes by rote, wanted more knowledge. He took the Rick Hansen Foundation Accessibility Certification™ (RHFAC) Training and received his RHFAC Professional designation to rate sites for their level of meaningful access. Erin said he also treats the RHFAC handbook as his “bible” when designing for accessibility, emphasizing the importance of approaching a space from the perspective of individuals with varying disabilities affecting their mobility, vision, and hearing, as well as from a neurodivergent perspective. Erin added that, by pursuing a rating, property owners and managers demonstrate their dedication to inclusion, and have a roadmap on how to continually improve upon their accessibility journey.

“Attitudinal barriers are probably the biggest barriers we have in society, but making buildings accessible is meaningful for people who have no voice in the conversation,” Erin said. “But you need the knowledge of RHFAC. The building code is just the bare minimum, and RHFAC is comprehensive. It’s about creating spaces that work for everyone, not just the perfect six-foot-tall man the industry typically designs for.”

Erin added that the difference is in the numbers: RHFAC’s handbook has more than 700 items that address accessibility while building codes typically have between a dozen and two dozen.

How Pedesting Came to Be

One of the early conversations between Erin and Nabeel was about power door openers, which, incidentally, are not included in code. Nabeel needed the assistance of a power door opener to exit a building and get to his ride. Erin was shocked when Nabeel told him how inconsistent they were – sometimes they’re there, sometimes they’re not. Often, they are difficult to locate.

“I remembered thinking, in this age of smartphones, why isn’t there an app that helps people navigate these barriers?” said Erin.

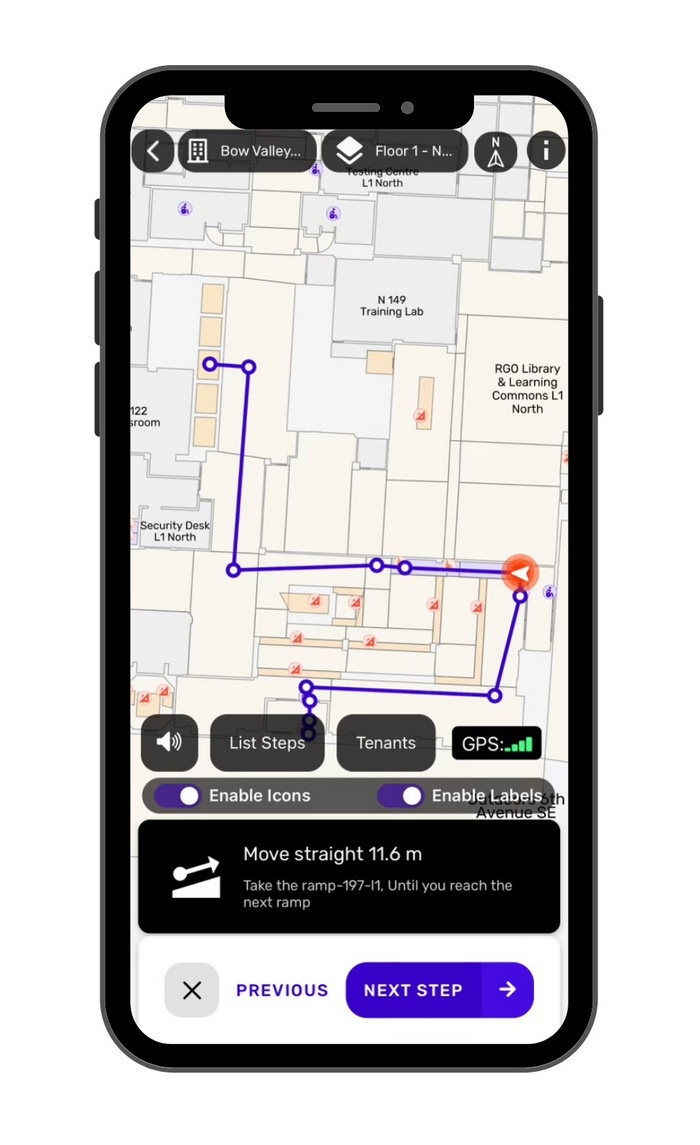

The idea blossomed into Pedesting, a technology-driven solution that maps out the easiest, safest, and most accessible pedestrian routes inside and outside buildings. Pedesting’s software takes a city’s pedestrian routes and architectural drawings of a building, identifies barriers such as staircases, and provides alternative paths, such as ramps or elevators, for people with mobility issues. Pedesting also helps building owners and architects understand the broader impact of accessibility.

While it started as a side project that Erin and Nabeel worked on during lunches, weekends, and late nights during their respective careers, they started working on Pedesting full-time, when the COVID-19 pandemic hit. They started small, working with local businesses and government agencies in Calgary. Still, their vision is much bigger: to reach a world where everyone with disabilities can navigate any space without barriers.

Pedesting now covers various downtown Calgary locations, including Bow Valley College, Arts Commons, Central Public Library, Calgary Telus Convention Centre, Stephen Avenue Place, Life Plaza, the Ampersand, and the Edison.

Even though it’s just a start in a single city, Nabeel said there is a need for the app to be present coast to coast as it removes some of the anxiety of navigating unfamiliar territory for people with disabilities. “There is so much uncertainty around going out. I often have to call the business owner ahead of time to see if the place is accessible,” he said. “It’s a lot of work.”

Even though it’s just a start in a single city, Nabeel said there is a need for the app to be present coast to coast as it removes some of the anxiety of navigating unfamiliar territory for people with disabilities. “There is so much uncertainty around going out. I often have to call the business owner ahead of time to see if the place is accessible,” he said. “It’s a lot of work.”

Pedesting is intertwined with RHFAC’s mission as Erin and Nabeel seek to educate building owners and site managers on the impact that thoughtfully designed, accessible spaces can have on communities, reinforcing the notion that access is a right, not a privilege.

“What I love about Pedesting is that it can provide accessibility right now, right out of the box. It’s not ideal because it’s a different route than what able-bodied people might take. It’s not Universal Design that we’re promising; we’re promising a way to get to your destination,” Erin said. “We’d like to think that building owners will think, ‘Wow, this is a drag that a bunch of people coming to my building have to take this weird way to get to my coffee shop.’ Then, hopefully, they will pursue an RHFAC rating to learn how to improve their accessibility.”

A Leap of Faith

In Calgary’s population of 1.6 million, it is estimated that there are 150,000 people with disabilities, many of whom face inaccessibility every single day. So, Nabeel said, many stay at home, choosing safety over the anxiety of exclusion. With Canada’s aging population growing in tandem with the increasing number of people with disabilities that count for 1 in 4 Canadians, this is a significant portion of people.

“We have this whole community that is out of sight, out of mind. It drives me crazy,” said Erin. “We’re missing out on so much talent and potential just because our buildings aren’t accessible.

For Erin and Nabeel, accessibility has become more than a professional challenge – it’s a moral imperative. “We’ve done big things as architects,” said Erin. “We’ve made changes that revolutionized the way buildings are designed. Why aren’t we now treating accessibility with the same urgency as climate change?”

The work of Pedesting and RHFAC is paving the way for that revolution. “The knowledge is out there,” said Erin, “Now it’s just about getting more people to care.”

To learn more about Rick Hansen Foundation Accessibility CertificationTM ratings and training, visit RickHansen.com/RHFAC