McGill University researchers say modern temperature control and ventilation design could be transformed with historic technique

Researchers from McGill University say that by revamping a forgotten heat recovery technique used in the design of Montreal’s Royal Victoria Hospital, modern temperature control and ventilation design could be transformed.

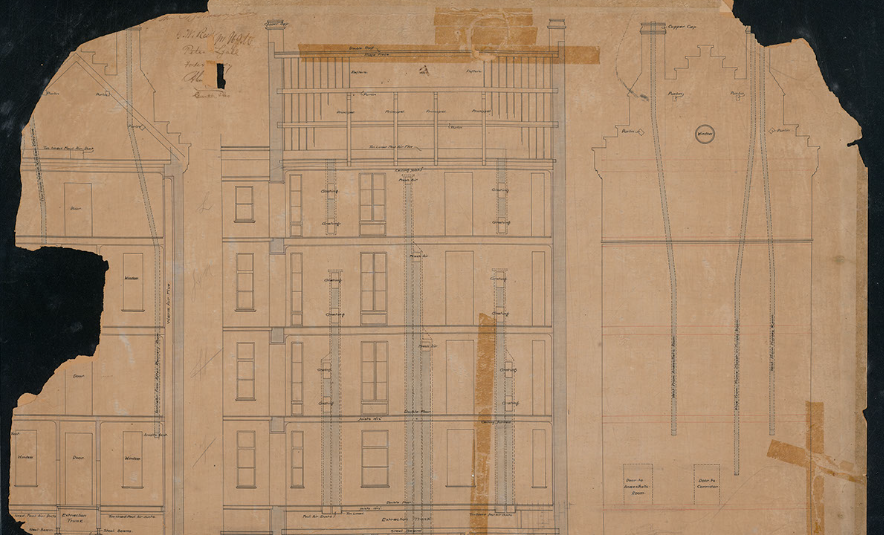

Researchers at McGill University’s Peter Guo-hua Fu School of Architecture recently examined the original ventilation system in Montreal’s Royal Victoria Hospital.

According to findings outlined in a recent article in iScience, the researchers said that by revamping the lost technique, modern temperature control and ventilation design could be transformed.

“These historical insights could help us to design less equipment-heavy solutions today with a new approach to energy-sufficient architecture and healthy indoor environments,” said co-author Professor Salmaan Craig.

The team for the Royal Victoria Hospital, built in 1893, found an early precedent for ventilation heat recovery. This was an efficiency measure that recuperated heat from the exhaust air so that stale, indoor air could be replenished with fresh, outdoor air.

“Ventilation heat recovery is vital for healthy, energy-efficient buildings but needs miles of ductwork. The supporting infrastructure causes substantial emissions during manufacture, maintenance, and disposal,” said Anna Halepaska, PhD candidate and the study’s first author.

Through research and lab experiments, the researchers verified the ventilation rate and amount of heat recovery of the thermos-hon system used at the Royal Victoria Hospital. They found that by revamping this technique, which operated without ductwork or fans, it was in fact possible to recover heat through partition walls and floors while also maintaining a steady ventilation flow.

The McGill team also found out how and why the system was originally designed in such a way by following a paper trail of correspondence between clients, consultants, architects and engineers.

“With windows more likely to be closed in the winter, patients would be warmed by fireplaces in the wards while fresh air, pre-heated to room temperature, would arrive from the ground-floor plenum,” they explain. “This warm air would naturally rise up through flues hidden in the exterior walls, circulating over patients, before exiting through a trunk in the attic as it was sucked out by a chimney.”

“Fuel economy and clean indoor air were real concerns in the 19th century, especially in hospitals. However, this early heat recovery innovation responded to the harsh Canadian winter on very pragmatic terms. It provided a means to preheat outdoor air, which stopped the pipework in the air heating system from freezing in cold snaps,” said Craig.

The researchers also clarified the role of British hospital specialist Henry Saxon Snell, who backed away from the project after developing its original designs.

According to the researchers, the board of governors pushed Snell to step down after local consultants argued his ventilation technique wasn’t fit for the cold weather.

The researchers proved the governors right and found out why Snell’s “scheme” was unfit while also revealing the method that replaced it.

“It’s also surprising that much of the ventilation design was inspired by a completely different building type—namely the Canadian Parliament building. Architectural historians sometimes think of hospitals as unique, but this work shows those crucial connections,” said professor Annmarie Adams, co-author and architectural historian.

By uncovering this early history of heat recovery, it puts a spotlight on the environmental ideas that motivated 19th-century engineers and architects in Canada and abroad.