Solar Flair: Windermere Fire Station No. 31, Edmonton, Alberta

A net-zero Edmonton fire station is topped with a sweep of solar panels.

PROJECT Windermere Fire Station No. 31, Edmonton, Alberta

ARCHITECTS S2 Architecture (Prime Consultant) with gh3* (Design Architect)

PHOTOS Raymond Chow, gh3*

Located in Edmonton’s far southwest, gh3* and S2’s Windermere Fire Station #31 casts a mountainous silhouette—capped with glimmering solar panels—against the vast Prairie sky. Windermere’s built form is remarkably close in execution to its early design, which won a 2018 Canadian Architect Award of Excellence. It delivers on dual promises: creating an expressive form that anchors its community, and performing as a net-zero building that wears its sustainability credentials on its sleeve.

As the design architect, gh3*’s team was faced with an uninspiring suburban site lacking the contextual depth of the firm’s other projects in Edmonton. In response, they decided to explore the archetypal idea of the firehall as a community building that blends technical and domestic space. While firehalls are first and foremost pieces of infrastructure for ensuring the safety of their communities, they are also second homes for the firefighters who live there while on duty, waiting for the next crisis to snap them into action.

The pairing of an apparatus bay for trucks and equipment with domestic dorms housing places to sleep, bathe, cook, and relax, results in two programmatic areas with significantly different heights. This invites the architectural response of designing the building as two distinct masses: “big volume, small volume,” as gh3* principal Pat Hanson puts it, a response that “is not very successful, in my mind.” In contrast, she notes that Windermere’s bold profile arose from the initial desires “to find a consolidated, unified form between these two very different programmatic pieces of the building […] combined with trying to find an approach that was expressive and sustainable.”

Working within the constraints of a municipal budget, Hanson and her team approached this task with the attitude of “just being respectful of the program and getting it right” and only having “one or two moves that carry the architectural idea, while being strategic about the other things so that they don’t take over.” On the exterior, these key moves included developing a unified mass, fitting the south-facing roof with an extensive solar array, and cladding the building in dark, woven masonry. On the interior, the program is arranged along a corridor circuit, and a glazed courtyard brings daylight into the central fitness area.

Achieving net-zero involved a blend of passive systems—thick insulation, high-performance windows, and atypical folding doors for the apparatus bay—along with two active ones, namely, geothermal heating/cooling and solar photovoltaic electricity production. While most of these features are all but invisible, the solar panels offered a chance to express the building’s net-zero status, and their optimal configuration helps define the gentle curve of the south roof.

The firehall’s pitched roof also sought to evoke façades of historic firehalls—the kind that still appear in children’s storybooks. “Firehalls ground communities,” says Hanson. “The emotional response to the firehall as a structure—particularly the old ones—is quite strong.”

Edmonton City Architect Carol Bélanger echoes this, arguing that firehalls can serve as meaningful “gateways to a community” instead of just being “located in a light-industrial area.”

How can a firehall be both an architectural landmark and a place of community pride? That question recalls architectural historian Kenneth Frampton’s comment, in a 2013 lecture on Alvar Aalto, that the most fundamental challenge facing architects today is “how to provide for a liberative modern environment, while still being able to embody a sense of security and rootedness without descending into kitsch.”

On this measure, Windermere partially succeeds. Without question, it’s a surprising, evocative form offering a sense of strength and security. The heavy visual presence of the black brick paired with the sloped profile, however, seems more likely to evoke Alberta’s beloved Rocky Mountains than historic firehalls. Imagining the same form constructed in red brick is an interesting exercise: the historic connection suddenly reappears, but now the building no longer appears contemporary, and even starts to recall the red brick masses of later Aalto projects.

This is no accident, since gh3* shares Aalto’s interest in the expressive and textural possibilities of brick. Hanson notes that brick was always the obvious choice for the project: it offers “feelings of permanence, security, wellbeing, comfort, and longevity”—exactly the values one would hope to find in a firehall. Brick also affords an incredible play of scale. “Because of the size of it, it allows for a form to be absolutely monolithic; you just don’t get that from metal panels.”

The sculptural possibilities of brick are apparent in the switch at the window datum from a regular bond to an open, woven pattern. The latter provides rich visual texture while toying with the solidity of the mass and making the most of the harsh Prairie shadows.

As you approach the building, the contrast between the fine-grained detail of the woven brick and the monumentality of the entire building is delightfully staggering.

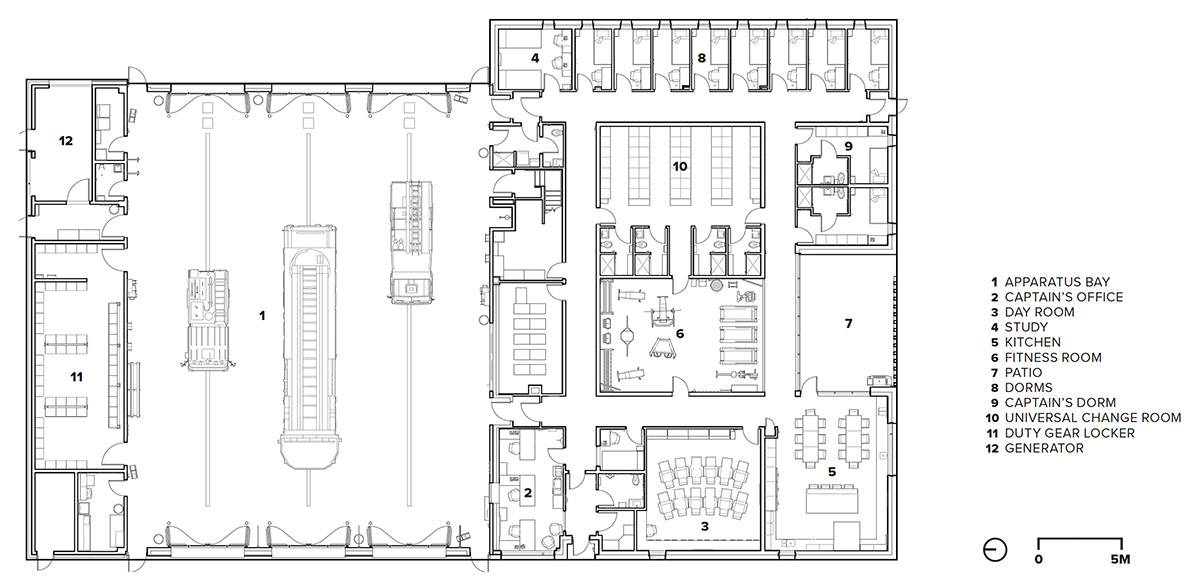

Windermere’s interior boasts a smart, well-organized plan that ensures firefighters can achieve rapid response times. The domestic area is organized around a corridor circuit, with the changerooms and fitness centre in the middle, and the sleeping areas, kitchen, lounge, and offices around the perimeter. Given the fraternal lifestyle of firefighters on duty, there is also a large south-facing courtyard for outdoor activities and cooking. A floor-to-ceiling glazed hallway links the courtyard to the gymnasium, bringing natural light into this deeper part of the plan.

The darker, monochromatic colour scheme of the domestic area—save for the orange accent of the gym floor—is a surprising contrast to the light, airy quality of the apparatus bay. One has to hope that the firefighters will bring some much-needed colour into these spaces as they occupy the building.

I toured Windermere with the project team shortly before it was occupied, and they discussed how the building was already garnering a lot of interest, perhaps ushering in a new paradigm for fire stations in the region. Using dark, patterned masonry for this typology already seems to have caught on: Edmonton’s under-construction Fire Station #3 Rehabilitation, by Winnipeg office 5468796, deploys charcoal concrete masonry units with rhythmic horizontal notches that enliven its facades.

Taking a long view, Edmonton’s fire stations have historically kept pace with progressive trends across the decades—from Moderne and the International Style, to Brutalism and Post-Modernism. Windermere points to a compelling next phase in this architectural evolution.

Greg Whistance-Smith is an Intern Architect in Edmonton, and author of the recent book Expressive Space: Embodying Meaning in Video Game Environments (De Gruyter, 2022).

PlanCLIENT City of Edmonton | ARCHITECT TEAM Linus Murphy, Ivan Sorenson, Grace O’Brien, Eric Klatt, Pat Hanson (FRAIC), Joel DiGiacomo, Mark Kim, Nicholas Callies | STRUCTURAL RJC | MECHANICAL/ ELECTRICAL Smith and Andersen | SUSTAINABILITY Ecoammo | CIVIL | LANDSCAPE gh3* / Urban Systems | INTERIORS gh3* / S2 | CONTRACTOR PCL | AREA 1,532 m2 | BUDGET $17.2 M | COMPLETION June 2023

ENERGY USE INTENSITY (PROJECTED) 94 kWh/m2/year (with solar panels operational, EUI will be 0 kWh/m2/year) | WATER USE INTENSITY (PROJECTED) 104 m3/m2/year