House Leader: West Block Rehabilitation Project, Parliament Hill, Ottawa, Ontario

PROJECT West Block Rehabilitation Project, Parliament Hill, Ottawa, Ontario

ARCHITECTS Architecture49 and EVOQ Architecture, architects in joint venture

TEXT Elsa Lam

PHOTOS Tom Arban Photography

In 1995, Quebec firms Arcop and Fournier Gersovitz Moss and Associates were hired by Public Works and Government Services Canada to rehabilitate the West Block on Parliament Hill. One of two buildings adjacent to Centre Block, the West Block was originally constructed in 1865 to house the Postmaster General, the Ministry of Public Works, and the Crown Lands Department. As the country and its administrative needs expanded, the building was added to in 1875-1878 and again in 1906-1909. But a century later, the masonry of the building was in a dangerous state of disrepair: protective fabric had been put in place around its towers in 2004 to protect the public from eroding mortars.

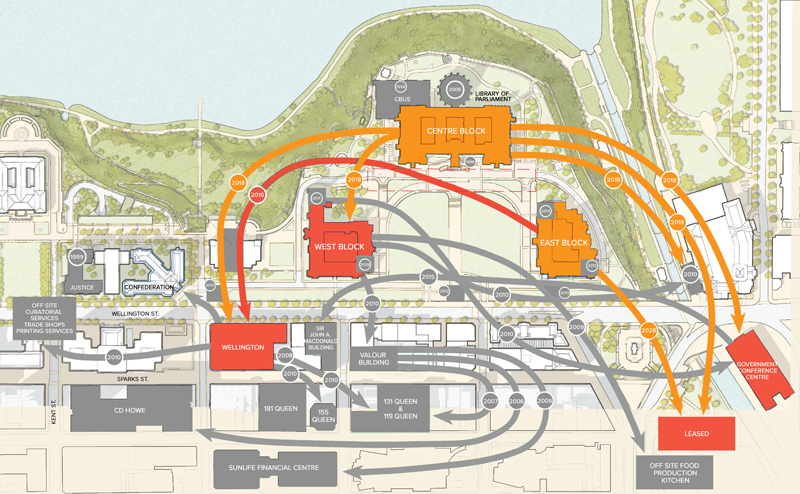

Design work began, but the project was put on hold in 1999 and did not go out to tender. Then its scope changed radically—from an already major restoration job to a comprehensive adaptive reuse that would transform the primary function of the West Block. Approaching the turn of the century, Public Works had been planning out how to perform restorative upgrades to Centre Block, which houses the House of Commons, Senate, Library of Parliament, and parliamentary offices. In 2001, they issued the first version of the Long Term Vision and Plan—a 25-year vision that maps out a cascade of building projects and moves needed to allow Centre Block to be vacated and renovated.

The lynchpin of the plan was finding spaces for the House of Commons and Senate—two very big rooms, whose configuration was fixed by codified parliamentary procedures. The Senate, it was determined, would temporarily decamp to the former Union Station, where meetings could be accommodated in a renovated rail concourse. The House of Commons required an even larger room. Luckily, there was a space with a large enough footprint in the Parliamentary Precinct. It was an unusual one, though: not an interior room, but the exterior courtyard of West Block.

More than two decades later, all three of the proponent parties have changed names: Fournier Gersovitz Moss rebranded as EVOQ, Arcop has become part of Architecture49, and Public Works is now Public Services and Procurement Canada. But a few members of the core design team remained involved throughout the process, and the house is now in session in its new home.

More than two decades later, all three of the proponent parties have changed names: Fournier Gersovitz Moss rebranded as EVOQ, Arcop has become part of Architecture49, and Public Works is now Public Services and Procurement Canada. But a few members of the core design team remained involved throughout the process, and the house is now in session in its new home.

In order to house the House of Commons, an enormous glass roof—about half the size of a soccer pitch—was constructed over the courtyard. Building a glass roof that large is an audacious move, made even more remarkable by several technical challenges particular to this site.

To start with, to avoid tampering with the heritage-listed West Block—one of North America’s largest load-bearing masonry structures—the new glass roof had to be self-supporting. On the surrounding edges, the glass needed to connect with a picturesque roofline that included projecting turrets, chimneys and vents. Moreover, because parliamentary proceedings are broadcast live, the space had to provide television-studio-grade lighting—free of glare and changing shadows. It also had to be acoustically impeccable to ensure speech intelligibility, even though microphones would be in place to enhance speech and to broadcast the proceedings.

“There are a few examples of courtyards that have been covered with glass roofs in the last 20 years, but they are primarily rectangular spaces with straight, level cornice lines,” says Rosanne Moss, who headed up the interior design of the project as a principal of EVOQ. “This space was a challenge: technically, it was a feat to cover this courtyard in a way that looks coherent and feels quite natural.”

EVOQ and Architecture49 devised a series of tree-like steel columns, inspired by the original building’s neo-gothic style, to support the roof. “In gothic architecture, often the structure is the architecture,” says Georges Drolet, lead designer and a principal of EVOQ. “The geometry of the structure is the foundation of everything that happens here.” The visual theme appears throughout the contemporary addition, including

in millwork panelling in the courtyard.

The 51-by-55-metre glass roof is a low, lens-shaped space in section, constructed like a bridge in order to clear the 44-metre-wide span of the courtyard. “One of the requirements was to minimize its visibility on Parliament Hill,” explains James Bridger, project architect and principal of Architecture49. As you approach the West Block, the glass roof is barely noticeable, which keeps the heritage building in the foreground. From inside, a clerestory is created between the glazed roof and the surrounding mansard-style roofs, with an array of bespoke connections to work around the historic roofs’ dozen protruding elements.

A triple-glazed set of panels tops the roof, with a single-glazed laylight at the bottom and a maintenance platform between. Geometrically, says consultant Marc Simmons of FRONT, the laylight panel layout is “chiselled like a diamond,” with symmetries that reinforce the gothic sensibility of the project. On the top surface, flush pressure plates connect the panels, ensuring that there are no protruding elements to trap snow and ice.

To meet the broadcast requirements, portions of the laylight are acoustically absorbent; in addition, perforated screens fill the branches of the tree-like columns, and transparent acoustic panels are hung from triangular supports along the roof’s centre line. The roof itself incorporates frits to diffuse light, and both fixed and operable louvres that can automatically adjust to changing daylight conditions. On the partially cloudy day when I visited, the light coming through the multi-layered construction was somewhat muted—an outcome, perhaps, of the tension between creating a glass roof while needing to protect the space beneath from glare, shadows and extraneous noise.

Instead of the television studio-style gantries that are typically used for broadcast lighting, the requirements were achieved using high-performance LEDs integrated into the architectural supports. “We’ve created a space that is achieving better acoustics and better lighting than the original chamber,” says Bridger.

The roofed courtyard is significantly larger than the actual House of Commons Chamber, so the interim Chamber occupies a screened area within it—analogous to a clearing in the woods, according to the designers. From the main level, it’s been made to accommodate the ceremonies of the existing House and reuse its furniture. There are a few minor upgrades and changes: the Members of Parliament in the rear rows get their own desks instead of having to share benches, and the Speaker’s Chair is an antique from the era when each Speaker had a bespoke chair. (It was originally made for the Honourable Edgar Nelson Rhodes, Speaker from 1917 to 1922.) The most dramatic view of the renovated courtyard is from the gallery level above, where the press and public convene

to watch debates. Here, the full extent of the glass roof can be appreciated, along with the stone walls and copper roofs that ring the large space.

These heritage façades have been meticulously restored to a shine that they had not seen for many decades. Previous to the renewal, the courtyard was used primarily as a service space and to house a 1960s cafeteria block, and its framing façades were badly neglected. Particular care was taken with the east wall, which was part of the original 1865 construction and designed to address an expansive lawn.

Overall, nearly half of the West Block’s exterior masonry—including much of the courtyard-facing block—was dismantled and rebuilt, and 14% of it was replaced—at the peak of the masonry rehabilitation, over 200 masons were working on the site. Laser cleaning tools were used to bring the stone’s original colours to life, and the grey mortar that had been used for repairs replaced with a black mortar similar in colour to the original soot-based formulation. The mortar lines make the individual blocks visually pop, showing off the zigzag lines of the sandstone trim around windows and the “crazy-quilt” of the spandrel panels—a pattern used to indicate their non-load-bearing nature. Within the courtyard, the visible copper roofs were repaired with oxidized panels selected for their green patina from existing portions of the roof, before the latter was re-finished with new copper. “You know you’re on the Hill, because this architecture is so present,” says Drolet.

Beyond the Chamber, the project involved excavating three new levels beneath the courtyard for committee rooms and mechanical spaces, seismically retrofitting the heritage masonry structure, and completely rehabilitating the interior of West Block, seamlessly integrating modern mechanical, electrical and IT systems. The building was last upgraded in the 1960s, when it was gutted from the basement up, and finishes were completely redone to the office standards of that time—complete with lay-in suspended ceilings and beige paint colours. The corridors had been left relatively intact, and have been carefully preserved in the current project. The grand stairs have also been restored, including the embellishment of the stair halls with colourful encaustic floor tiles that recreate nineteenth-century originals found at the main entrance vestibules.

The most ornate area of the original building was the 1878 Mackenzie Tower, designed by Prime Minister Alexander Mackenzie, who served concurrently as Minister of Public Works and had apprenticed as a stonemason. Mackenzie’s offices, housed in this section, were a natural fit for converting into parliamentary offices. During the restoration of the heritage ceilings and plasterwork in this area, the architects discovered details such as a series of late Victorian tiles embedded in the plaster cornice that had been covered over in the 1960s.

Throughout the interior design, care was taken to respect the subtle difference between styles in the different wings of the building. “The 1860s wing is rather unadorned for a neo-Gothic building—the country was new, and it was a building to house civil servants—and we took our cues from that,” says Julia Gersovitz, a principal of EVOQ, who has been partner-in-charge of design and conservation since the project’s inception in 1995. “It’s not a very fussy or ornate [part of the] building, and it’s remained true to its period and what it was. The 1878 wing was much more ornate.”

Interiors that were built from scratch, such as the committee rooms in the newly excavated areas beneath the courtyard, were designed to be distinguishable from, yet compatible with, the nineteenth-century building. Technology and accessibility have been integrated into all spaces, helping the building function as a twenty-first-century workplace.

Another aspect of the restoration was a reconsideration of the entrance sequence. Instead of coming through the main doors facing Wellington Street or through the Mackenzie Tower, visitors now enter from the underground Visitor Centre. The north wing of the building—too narrow to comfortably accommodate offices—was reconfigured as a large lobby space, with entrances to committee rooms and a lantern-like stair leading to the Chamber and its galleries. The stacked lobbies allow visitors to orient themselves: windows on one side look out to the Centre Block, while across the room, one can see the courtyard and interim Chamber. “A big piece of the design was creating a ceremonial, processional way of getting into the building,” says Moss. In the 1960s, the Wellington Street entrance was lowered from the second level to grade; the current renovation restores the elevated “piano nobile” as the main floor of the building.

Much changes over the course of a 24-year-long project. “We fulfilled our initial mandate from way, way back—we rehabilitated West Block according to the new standards,” says Bridger. But in the process, he adds, “the National Building Code evolved, security requirements evolved, Parliamentarians’ needs evolved, technology evolved, accessibility—all of these things evolved as we were designing the project. We were able to respond to each of those new requirements, and still maintain an overall project vision that was rooted in the rehabilitation of an icon.”

Eventually, the House of Commons will return to Centre Block. There is as yet no clear picture of what the courtyard will then be used for—a secondary Chamber, a formal reception area, committee rooms, or infilled offices are some of the possibilities. The rehabilitation has been designed to accommodate such changes, with components such as its acoustic panels made to be easily removable, and designed with less preciousness than permanent elements such as the glass roof. When the space has evolved into its next iteration, Parliamentarians will return to a legacy Chamber that will be renewed, in part, by the same architects. Architecture49 won a bid to restore Centre Block, working with WSP and HOK. It will be the largest and most complex heritage rehabilitation project ever seen in Canada—a challenge for heritage architects and craftsmen that will rival the impressive work already completed at West Block.

Elsa Lam is Editor of Canadian Architect.

CLIENT Public Services and Procurement Canada | ARCHITECT TEAM Architecture49—James Bridger (RAIC), Bruno Verenini (FRAIC), Norman Glouberman (FRAIC), Arne Sideco, Bozena Jaworska, Joel Prefontaine, Yekaterina Artemchuk, Tina Nuspl, Fabiana Namba, Dave Lemieux, Alex Smyth, Rene Mariaca, Amanda Gilbert, Christopher Blood, Sally Vandrish, Laura Lynn Da Silva. EVOQ— Rosanne Moss (FRAIC), Georges Drolet (RAIC), Julia Gersovitz (FRAIC), James L. Curtiss, Catherine Fanous, Jayant Gupta (RAIC), Lee-Christine Bushey, Chloe Blumer, Elizabeth Caron, Troy Tyers, Bryan Mendez, Marie-Joelle Larin-Lampron, Hilary Farmer, Jean-Benoit Bourdeau, Francis Tousignant, Darryl Aldrich. | STRUCTURAL Ojdrovic Engineering and John G. Cooke and Associates | MECHANICAL/ELECTRICAL Crossey Engineering | LANDSCAPE Groupe BC2 | CIVIL Golder Associates | GEOTECHNICAL Golder Associates (design) and Paterson Group (site supervision) | FAÇADE FRONT | ACOUSTICS State of the Art Acoustik and Acoustic Distinctions | CLIMATE ENGINEERING Transsolar KlimatEngineering | SUSTAINABILITY WSP Canada | LIGHTING OVI and Gabriel Mackinnon Lighting Designers | COMMISSIONING VSC Group | ELEVATORS EXIM | FOOD SERVICES WSP Canada | FIRE AND LIFE SAFETY Morrison Hershfield | COSTING Hanscomb | SCHEDULING Delsaer Management | ENVIRONMENTAL T. Harris Environmental Management | SECURITY Groupe SM | BLAST ENGINEERING Hinman Consulting Engineers | WIND RWDI | HARDWARE JKT Consulting | SIGNAGE JaanKrusbergDesign | MASONRY Consultant in the Conservation of Historic Buildings and Capital Conservation Services | IRONWORK Craig Sims Heritage Building Consultant | PLASTER RESTORATION Historic Plaster Conservation Services | ENVELOPE WSP and Quirouette Building Specialists | STRUCTURAL CODE ANALYSIS Robert Tremblay | SPECIFICATIONS Circumspect | CONTRACTOR PCL Constructors Canada | AREA 30,598 m2 | BUDGET $863 M | COMPLETION September 2018

Energy Use

ENERGY USE INTENSITY (PROJECTED) 458 kWh/m2/year | WATER USE INTENSITY (PROJECTED) Less than 1.5 m3/m2/year | WATER USE INTENSITY BENCHMARK 1.59 m3/m2/year for office buildings constructed before 1970 [Real PAC]